Telita Snyckers ■ Switzerland’s tax referendum is a choice between tax havenry and more tax havenry

Corporate taxation in Switzerland has about as many holes in it as its famous cheese does. That is possibly about to change (although whether for the better or the worse is up for debate.)

Introduction of a minimum global tax rate in the EU

On 12 December 2022, the EU adopted the proposal for a Council Directive to introduce a minimum tax rate of 15 per cent for multinational enterprise groups and large-scale domestic groups in the EU. The proposal relates only to groups with combined financial revenues of more than €750 million a year. In practice, if the effective tax rate for the group is below the 15 per cent minimum, it will have to pay a top-up tax to bring its rate up to 15 per cent.

EU member states need to implement the new rules by 31 December 2023.

Why a minimum corporate tax rate is important

Low corporate tax rates have become a blunt tool used to get large corporates to establish themselves in a particular jurisdiction. But in doing so, it becomes a race to the bottom, with countries punting ever lower tax rates.

Tax competition is a false economy.

The Tax Justice Network has long argued that these strategies that are pursued in the name of a euphemism like “competitiveness” or “open for business”, are little more than a woolly-headed concept. These “competitive” incentives are always directly harmful to the wider public interest. Even in the cases where tax cuts do attract investment, it attracts exactly the wrong kind of investment: the flighty kind with few productive linkages with the rest of the economy.

A global minimum tax rate, if done right, can help prevent multinational corporations and wealthy individuals from exploiting tax loopholes and artificially shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions. It also helps in reducing the incentive for companies to engage in harmful tax competition, where they relocate or shift profits solely for tax purposes. In the process, it prevents the kind of profit shifting and tax abuse which is eating away at the public funding countries need for public services, infrastructure development, and social welfare programs.

Sadly, negotiations at the OECD have beaten the global minimum tax rate down from a timid 21 per cent rate – initially proposed by the Biden administration – to an ineffectual 15 per cent. Calls from lower income countries and the UN for substantially higher minimum rates – closer to widely held statutory rates – have been completely ignored in the process. With the rate set far below most countries headline corporate tax rates, the deal will unashamedly benefit rich tax havens that are members of the OECD like Ireland, Luxembourg and Switzerland.

What started as a speed limited for tax havens is now a rewards programme for tax havens – and in Switzerland’s proposed local implementation of the deal, a rewards programme specifically for tax abusers based in Switzerland.

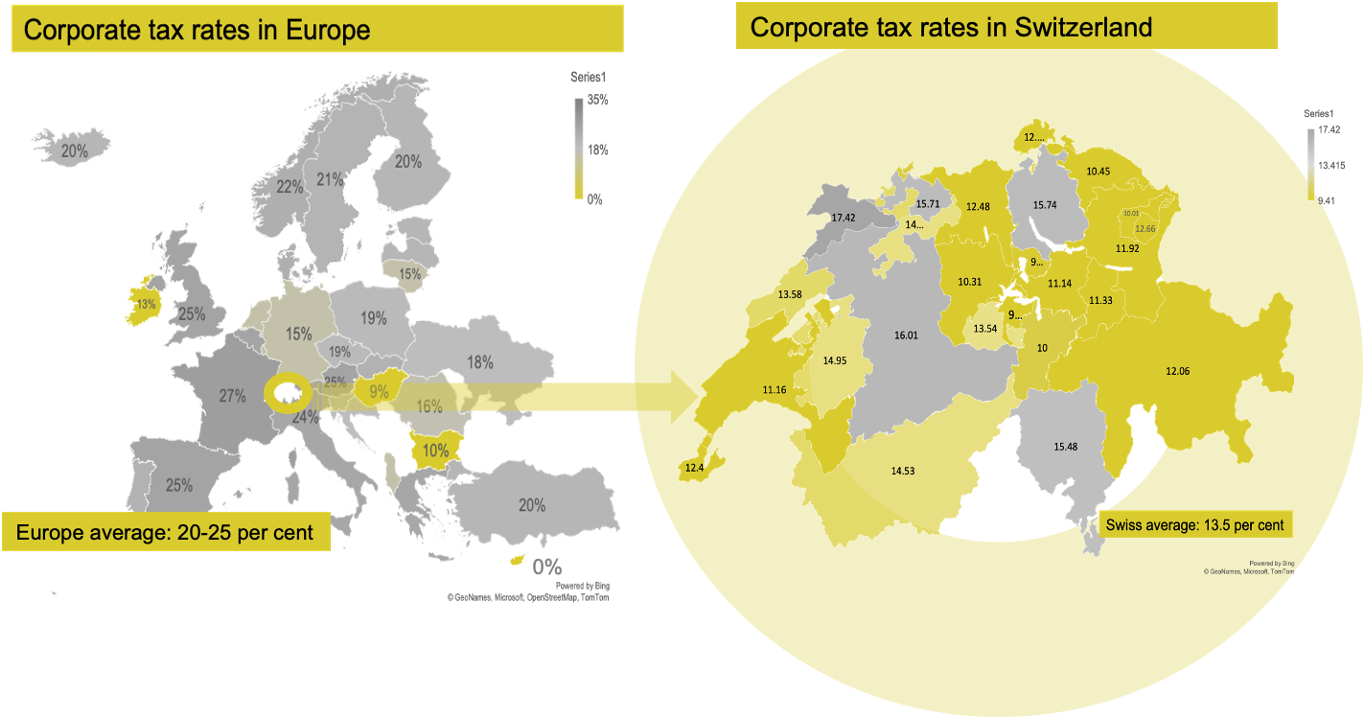

Current corporate tax rates in Europe

The importance of establishing a global minimum tax rate is evident when one considers the current corporate tax rates across eg Europe in general, and a country like Switzerland in particular.

The average corporate tax rate in Switzerland is 13.5 per cent. Of its 26 cantons, 21 have tax rates well below the minimum 15 per cent threshold set in the new EU rules. In some of its cantons, the tax rate is as low as 11 per cent (Basel-Stadt, Zug and Nidwalden).

The situation is even worse when you consider the fact that corporate tax havens like Switzerland often allow multinational corporations to pay corporate tax rates that are far below the headline corporate tax rate. For example, our 2021 Corporate Tax Haven Index found that some companies exempted from Switzerland’s tax reform could potentially be allowed to pay a corporate tax rate as low as 2.61 per cent.

Of course, it’s not just Switzerland that has artificially low corporate tax rates. Switzerland ranks 5th on our Corporate Tax Haven Index 2021, which is a ranking of countries most complicit in helping multinational corporations underpay tax. Other countries in the region that rank high on the index are Netherlands (4th), Luxembourg (6th), Jersey (8th) and Ireland (11th).

Netherlands and Luxembourg both have headline corporate tax rates of about 25 per cent, but both were found by the 2021 edition of the Corporate Tax Haven Index to have tax rulings in place that permit corporate tax rates as low as 5 per cent in Netherlands and 0.3 per cent in Luxembourg. Ireland has had had a headline rate of 12.50 per cent but had tax rulings permitting 0.005 per cent corporate tax rates, while Jersey set its headline tax rate at 0.

The only purpose of the artificially low tax rates is to entice corporates to be based there. Holistically viewed, this is problematic because it does not bring real economic activity to the region – it simply shifts profits there, from the jurisdictions where the economic activity is actually happening (and where taxes should instead be paid.) Some US$ 1 trillion is shifted to tax havens every year, and as our State of Tax Justice 2021 report shows, Switzerland alone cost the rest of the world at least $19 billion in lost tax a year by enabling corporate profit shifting.

Switzerland voting on introducing a minimum corporate tax rate

The Swiss parliament has translated the OECD minimum tax rules into a “national supplementary tax”. This will see multinational enterprises in Switzerland having to pay a top-up tax to raise their effective tax rate to a minimum of 15 per cent.

On June 18, the issue goes to the polls in Switzerland.

For Switzerland to implement the new EU rules, the federal government needs to intervene in the otherwise tax-sovereign cantons. Because of this, and because the change would result in differentiated treatment for certain classes of taxpayers (the largest corporate taxpayers), it constitutionally requires a public vote before a minimum tax rate can be introduced across Switzerland.

The Swiss vote is a false choice between tax havenry, and more tax havenry

At face value the Swiss vote seems to suggest a move towards undoing the country’s status as a tax haven. It’s an illusion: the choice is effectively between staying a tax haven, or becoming even more of a tax haven. The top-up tax is misleadingly being presented as an anti-tax havenry choice.

Public debate on the new measure has largely framed the measure as something Switzerland ought to do on in own terms and beat other countries to the punch on, rather than be pressured into it down the road under less favourable circumstances. Former Swiss Finance Minister Ueli Maurer made the calculation quickly: “If Switzerland doesn’t take the extra money, others will.”

But as Dominik Gross from Switzerland’s Alliance Sud explains, if Swiss citizens vote in favour of the minimum tax rate, rather than bring an end to the race to the bottom, the new rules will instead preserve Swiss tax havenry in a perfect, perverse loop. As Gross explains, “If Switzerland decides to adopt a minimum tax and to apply it to multinational groups in line with the OECD’s suggestions, it pre-empts other countries’ possibility under the same OECD rules to recuperate some of the tax on undertaxed Swiss income. Much of this income shouldn’t be Swiss income in the first place, given that it also includes profits shifted away from subsidiaries in those other countries.”

The potential spill over impact on other countries is significant. Switzerland is the country with the highest density of multinational corporations in the world, the home of some of the biggest financial companies in the world, and of very prominent players in the pharmaceutical, food and commodity trading industries. Instead, as Gross goes on to explain, “countries currently losing out on tax revenue to multinational enterprises using Switzerland’s tax havenry services won’t be empowered by the OECD’s global minimum tax rules to recover that lost tax revenue. Instead – shamefully – the OECD’s new rules will reward Switzerland’s decades-long harmful behaviour while multinational enterprises continue to underpay tax, particularly in the global south, as usual.”

It gets worse: Switzerland plans to use the additional revenues from the top-up tax to further improve Swiss “competitiveness,” through reductions in capital taxes or personal income taxes; the state taking over part of the companies’ operating costs; research promotion measures for start-ups; and direct subsidies for wages paid by corporations.

In practice, a vote for the minimum top-up won’t end Swiss tax havenry, but will instead amplify and rubberstamp it. Ultimately Swiss voters are being asked to choose between keeping Switzerland’s corporate tax havenry as is – or making it worse.

Issues with the current discourse on a minimum global tax rate

The Swiss vote is important for many reasons: if it passes, it will likely have a significant impact on the local economy, but also a broader impact on the taxing rights of other countries.

While the new EU rule rightly recognises the need to stop the race to the bottom, in its current formation it does nothing to stop it. Worse, it rubberstamps it. The current discourse positions a global tax rate – for EU companies, at least – at far lower than the 21 – 25 per cent that had originally been discussed. The USA has also already noted its unwillingness to adopt a minimum global rate in principle. And so, regardless of this particular vote, more work is needed to ensure traction for a minimum corporate tax rate in Europe, and beyond.

The tides are turning against tax havens: polling data from seven leading countries shows overwhelming public support for policymakers to crack down on companies using tax havens. The polling, conducted in the USA, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands and the UK, asked participants for their views on tying government bailouts (during the coronavirus pandemic) to companies’ record on paying tax, and cutting their ties with tax havens. An overwhelming 87 – 95 per cent of respondents supported the idea.

Image: Dmitri Popov dmpop, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Related articles

The Bitter Taste of Tax Dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss Swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025