Telita Snyckers ■ 5 ways Big Tobacco is making you pay more tax

“One comes to the conclusion that you are either crooks or you are stupid, and you do not look very stupid.”

UK Parliamentary Committee hearings into tobacco smuggling, to the CEO of Imperial Tobacco

Tax justice and tobacco

At the heart of tax justice is the idea that everyone, everywhere, should pay their fair share of taxes. When they don’t, it results in an increased tax burden on the compliant few, in a decreased availability of funding for fundamentals like access to schooling, healthcare and social safety nets, and in an increase in the reliance on third-party funding, which reduces a country’s sovereignty.

By contrast, if one were to craft a poster child for tax “injustice” it would probably look a bit like this: a corporate bully making products that kill half its clients, costing our governments more in healthcare than they make from tax revenues. Its business model would be built on illicit, untaxed supply lines, and shifting what profit it doesdeclare to tax havens. All the while illegally spying on its competitors, polluting our beaches and stripping our forests, and hopping in bed with North Korea. And it gets away with it because it has captured the very same governments that are meant to regulate them.

They exist, and are collectively referred to as “Big Tobacco.”

Their business model comes at the expense of other taxpayers. Healthcare costs exceed tax revenues from tobacco companies. There is no accountability for cleaning up the pollution they leave behind (with the financial burden instead falling on society). Their abusive profit shifting leaves them paying obscenely low effective tax rates. Their opaque supply chains let them freely pump cigarettes into illicit markets, no taxes or duties paid. And they use illicit financial flows to launder ill-gotten income.

Unwavering profitability

The tobacco industry is unwaveringly profitable. British American Tobacco, for instance, has been the best performer on the UK stock market over the past 35 years. In global terms, while the volume of cigarettes sold may have decreased, its value has increased. There is a simple reason for its continued success: the multinational tobacco companies are masterful at keeping both their supply chains and finances almost entirely opaque, emboldened by the criminality that is hardwired into its very DNA.

Tobacco is the most widely smuggled legal substance in the world, with profit margins on a smuggled (that is, tax free) container of up to 2,400 per cent – making it more profitable than heroin, cocaine or arms, but with far less risk of imprisonment.

Most criticisms of the tobacco industry arguably focus on their marketing of addictive, killer products, but there is so much more about them that is “unjust,” starting, perhaps, with the fact that their tax contributions don’t cover the healthcare costs that arise from smoking.

1. Taxpayers spend more on the healthcare costs of smoking than big tobacco contributes in tax

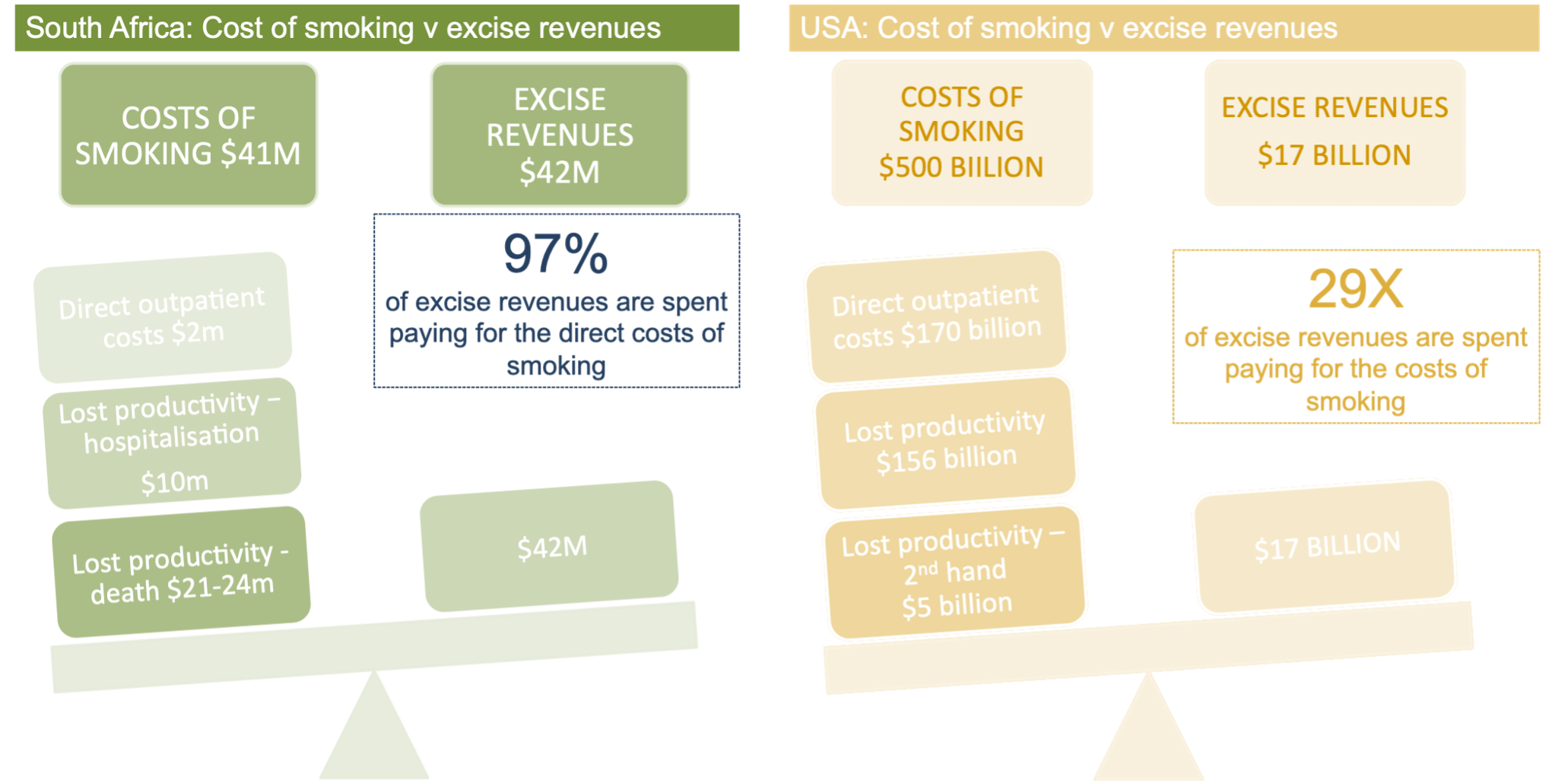

Excise duties are different from other taxes, in that their primary purpose is to drive specific behaviours, by taxing public “bads,” and to help to compensate for negative impact they have on our societies. So it makes sense that excise duties are levied on tobacco products.

Unfortunately, they don’t nearly cover the healthcare costs of smoking.

Instead, smoking is a net negative for most nations, costing the world more than US$ 1.8 trillion annually in healthcare expenditure and lost productivity. Smoking costs us – as taxpayers – the equivalent of 1.8 percent of global GDP, every year.

A research paper on the health and economic burden of smoking in 12 Latin American countries exposes how health-care costs attributable to smoking represent 6.9 per cent of the overall health budgets of these countries – tax revenues from cigarette sales cover only 36 per cent of these expenditures.

It is an easy enough analysis to replicate on a country by country basis, by comparing the cost of smoking to the excise revenues collected. In South Africa, for instance, 97 per cent of excise revenues are spent paying for the direct costs of smoking alone (in other words, not accounting for any of the indirect costs like loss of productivity or second-hand smoke). In the USA, more than 29 times the amount collected through excise duties is spent on healthcare for smoking-related diseases.

At a minimum, policymakers should introduce duties and taxes that at least fully compensate for the direct healthcare costs of smoking.[MBM2]

But of course, tobacco companies don’t only pollute our lungs, they pollute our beaches too.

2. The tobacco industry’s pollution costs millions to clean up

As Tobacctactics reports, the tobacco industry’s emissions are larger than those for entire countries, including Denmark and Croatia – comparable to emissions from the oil, fast fashion and meat industries; and the tobacco product life cycle releases 80 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent every year. If cigarette production ceased tomorrow, it would be equivalent to removing 16 million cars from the roads each year.

Cigarette butts are more than just unsightly – the filters contain single-use, non-biodegradable plastic and toxic chemicals, leaving 175 tons of waste behind every year, and making up 38 per cent of all beach waste.

In addition, tobacco farmers who handle crops are exposed to a substantial amount of nicotine – the equivalent of smoking 50 cigarettes a day.

This not being devastating enough already, more than 600 million trees [AC3] are cut down every year to cure tobacco leaves, and another 9 million trees to make matches. British American Tobacco, for instance, stands accused of being responsible for 30 per cent [AC4] of the total annual deforestation in Bangladesh, cutting down 200,000 hectares a year. The industry’s reforestation programs are having little discernible impact on deforestation, planting non-indigenous, thirsty eucalyptus trees which are not intended to replenish the destroyed forests but for use in tobacco curing.

Other public “bads” are being made to pay for the damage they cause to the environment: plastic waste, air pollution, unleaded petrol and lightbulbs.

“Polluter pays” is a principle in international environmental law aimed at making polluters pay for the cost of their environmental harms, which can be further broadened to make the producers of polluting products accountable for ensuring the product can be responsibly disposed of (as is the case, for example, with paint in the US).

Calls in the UK for a windfall tax on tobacco multinationals are a welcome development. A “polluter pays” levy, and a windfall tax on tobacco multinationals could raise a combined £774 million a year in additional tax revenues – in the UK alone.

Oluwafemi Akinbode of Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa has suggested that litigation against oil company Shell in the Niger Delta could provide a template for introducing a more just approach in the tobacco industry.

That should reasonably include commitments to:

- Introduce climate justice perspectives in debates around tobacco regulation

- Implement the “polluter pays” principle in the tobacco industry, and hold the industry to account for clean-up cost reimbursements

- Introduce extended producer responsibility to make tobacco multinationals accountable for ensuring their product can be responsibly disposed of.

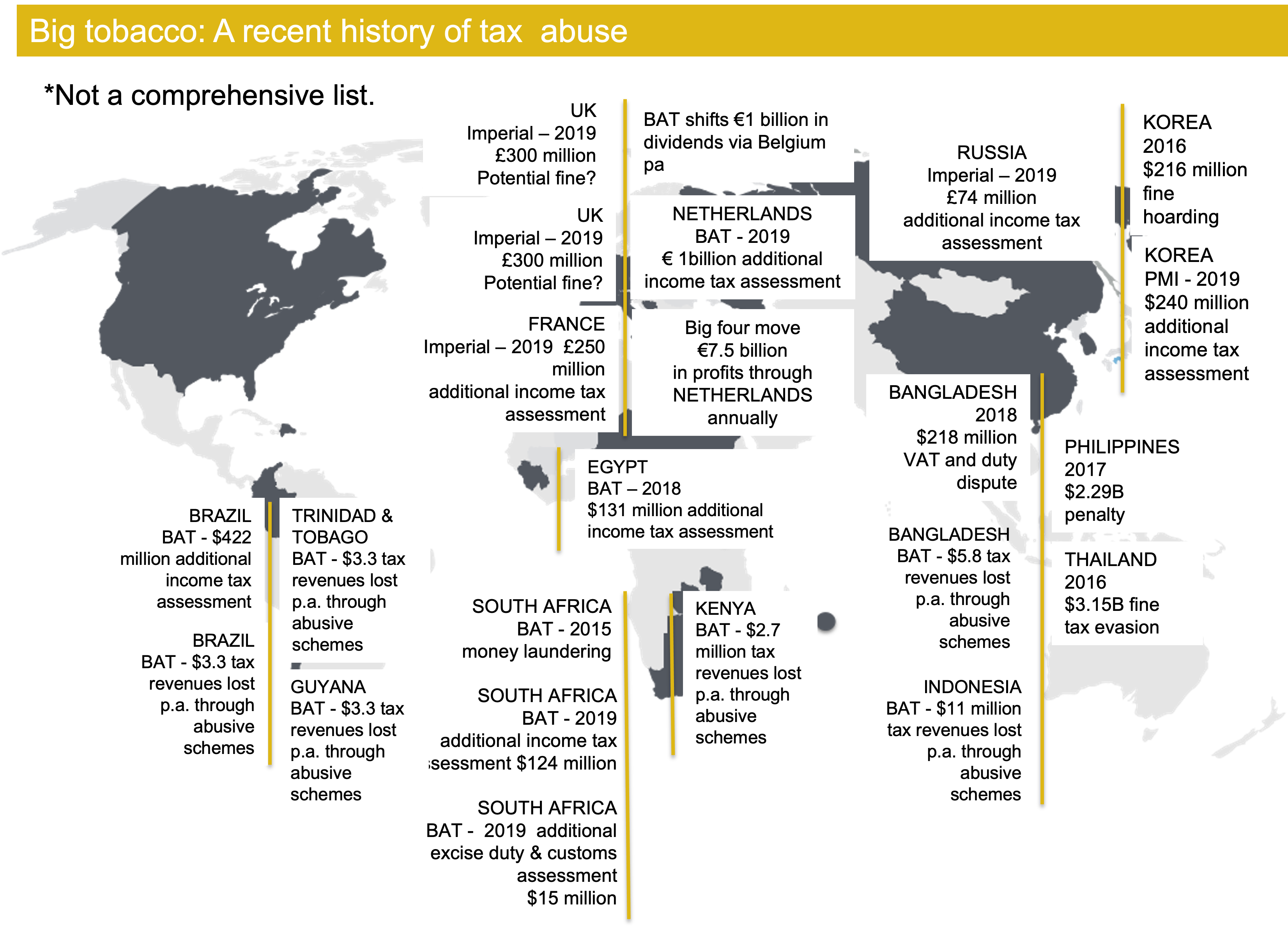

3. Big Tobacco underpays its taxes ever year

At the British American Tobacco annual general meeting in 2014 an activist asked, “Mr. Chairman, I note that BAT reports on the amount of corporation tax paid in the UK (which appears to be zero) and the amount of corporation tax paid overseas, without providing a breakdown of the countries comprised within the overseas heading. The Sustainability Summary states that ‘Transparency is important to us’. With the importance of transparency in mind could you let us know in what countries the company does pay corporation tax, and can you confirm whether the company would be open to providing a country-by-country breakdown of taxes paid in annual reports in the future?” BAT’s CEO responded simply that there was “no need to report globally.”

In our 2019 report, Ashes to Ashes, the Tax Justice Network estimated that in Bangladesh British American Tobacco managed to shift $21 million in profits through royalties and IT charges, costing the country $5.8million in lost taxes. In Indonesia, they shifted $73 million through loans and royalties, costing the country $13.7 million in lost taxes. By booking Brazil’s profits in Madeira, they managed to shift $110 million out of the country, costing Brazil $33 million in tax revenues a year. In Kenya, by shifting dividend payments to the tune of $26 million, they avoided payment of $2.7 million in local taxes annually. Over the course of a decade these practices could have cost countries around the world $700 million in lost tax revenues.

Companies pay themselves royalties, management fees and IT charges. They lend themselves money. They send profits back home, away from where the commercial activity takes place. There may often be no commercial substance to these payments, instead existing solely or mainly to reduce the groups’ tax liability. And while the schemes involved are similar to those used in criminal activities, they get away with it all because multinational companies can back up what they do with opinions from tax advisers that make it difficult to establish the intent necessary for a criminal offence.

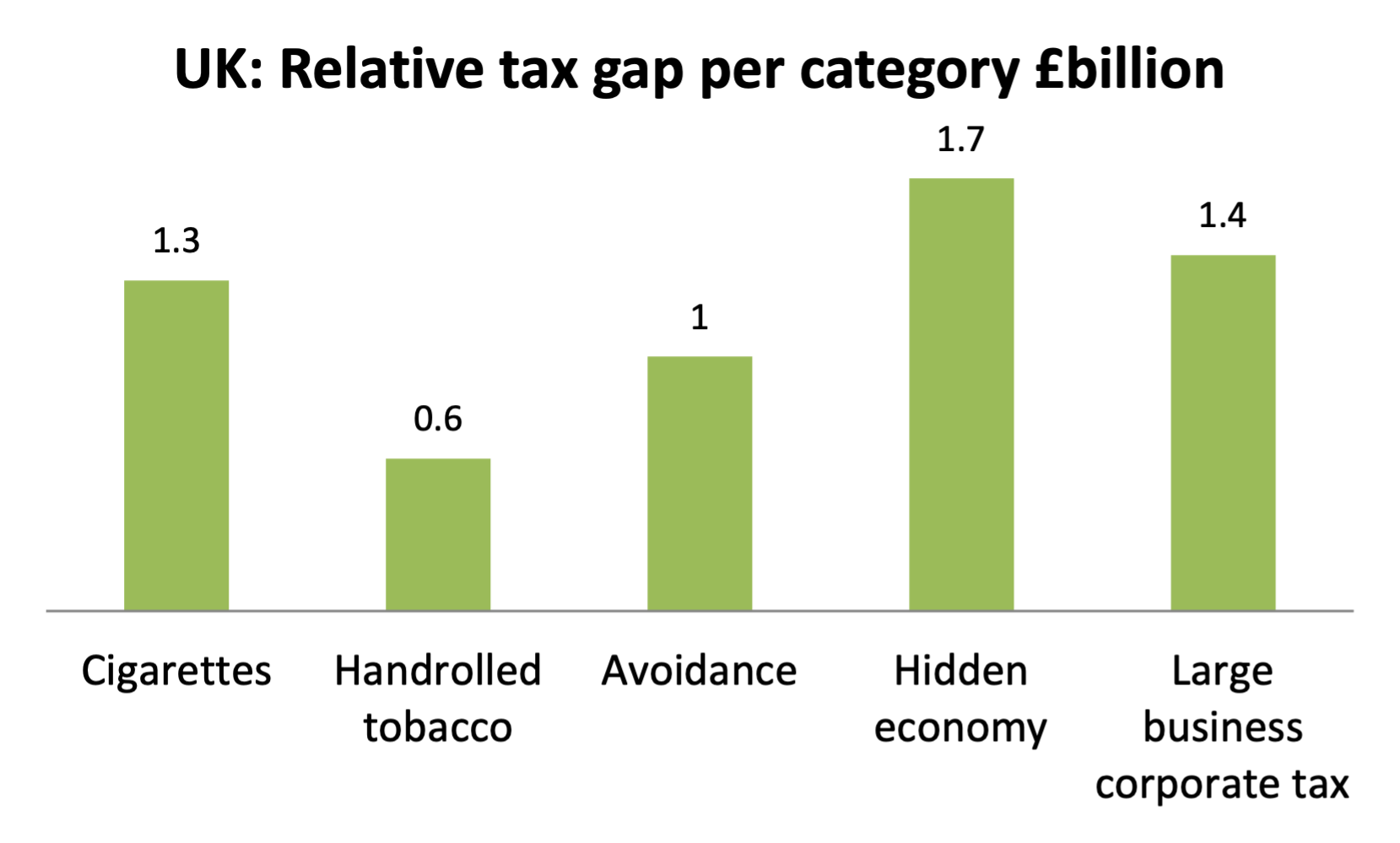

Grossly abused rules on taxpayer secrecy provide a veritable invisibility cloak to multinationals, making it extremely difficult to assess with any certainty the extent to which multinational companies are taken to task by tax administrations. While many of the investigations into their practices are opaque, there are some clues: estimates, like the ones in our report Ashes to ashes, and the comprehensive tax gap analysis done by HMRC in the UK; occasional disclosures by whistle blowers; and – historically – disclosures made by the companies themselves in their annual reports.

British American Tobacco unfortunately does not publish details of its contingent liabilities in its annual reports anymore, but when it used to, no fewer than 15 pages of their annual report were dedicated to listing tax abuse lawsuits it was defending across the globe. In the last report where these “contingent liabilities” were disclosed, they were facing an additional tax assessment of $124 million for aggressive tax planning using debt financing structures in South Africa, a $422 million income tax assessment in Brazil, a VAT and duty dispute to the tune of $218 million in Bangladesh, and a $131million tax assessment in Egypt. Altogether, the potential liabilities – should they fail to successfully challenge the assessments – total some $2.1 billion. That’s just for one year.

(The other Big Tobacco companies unfortunately don’t publish similar information. We back the tax standard of the leading international sustainability standards setter, the Global Reporting Initiative, under which companies’ uncertain tax positions should be reported, by country.)

In the following year British American Tobacco was sued by the Dutch government for €1billion for tax evasion (it had paid £1.6 million in tax on income of £1.6 billion – a tax burden of 0.1 per cent). British American Tobacco also shifts €1 billion in dividends via Belgium each year, again paying less than 1 per cent tax.

By underpaying tax at a colossal scale, Big Tobacco companies shift the tax burden even further on to the shoulders of ordinary taxpayers. This is tax burden made a lot heavier by the healthcare costs and environmental costs of smoking.

- The Tax Justice Network’s recommendations in this area address both tax and transparency. We call for international tax rules to eliminate profit shifting by taxing multinationals according to the location of their real economic activity, and with an effective minimum rate. On transparency, necessary steps including public country by country reporting on the GRI standard, with full disclosure of uncertain and contested tax positions, and greater transparency about anti-abuse investigations of tax authorities.

4. Big tobacco knowingly supplies the black market

As much as 98 per cent of illicit trade in tobacco comes from legal manufacturing operations, many of which are owned, operated by or contracted by the four big tobacco companies, which continue to control more than 80 per cent of the world’s tobacco market. The math is obvious: if there is a significant illicit trade problem, it cannot exist without the involvement of the big four tobacco companies.

Indeed, evidence shows that the multinational tobacco companies are not only peripherally involved in supplying illicit markets, it is an explicit part of their business model.

In May 2023, news broke of British American Tobacco having signed an agreement with the US to pay more than $629 million in fines, to settle claims relating to the “formation of a conspiracy to export tobacco products to North Korea and receive payment for those exports through the U.S. financial system” between 2009 and 2016. (With criminal investigations typically having long lead times and lifecycles, 2016 is pretty recent.) In the process, British American Tobacco moved over $250 million in sanctions-busting profits out of North Korea.

This US settlement speaks only to the fact that British American Tobacco consciously and knowingly set out to circumvent sanctions. It doesn’t even begin to speak to the tax consequences of the “joint venture” in question.

There is nothing particularly shocking about this revelation, with questions about their involvement in North Korea and their dealings through Singapore having been raised for some time.

It’s a textbook example of the impunity with which multinational tobacco companies act: selling killer products in a prohibited market, then laundering the profits, all while paying little to no domestic duties on the cigarettes sold, or income tax on the downstream profits.

There is incontrovertible evidence of multinational tobacco companies benefiting from the smuggling of their own packs: in some instances, through “indiscriminate sales” where they choose not to track how the packs end up in illicit supply chains, but more often through structured, planned, organised schemes selling what they colloquially may refer to as “duty not paid” cigarettes, through corporate structures aimed at making their supply chains as opaque as possible.

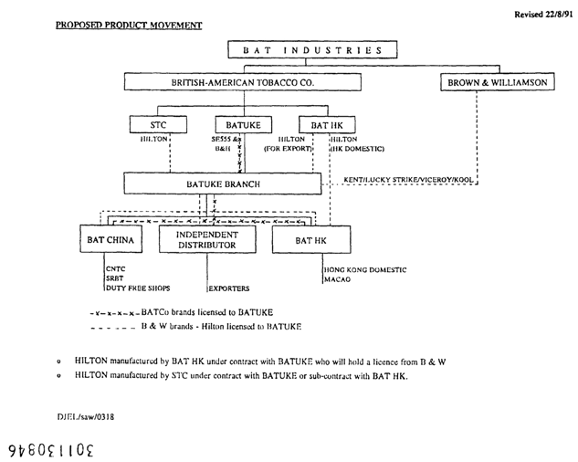

Schemes like the one British American Tobacco ran in North Korea. Or their well-documented structure in the 1990s which explains how they did something similar through Hong Kong.

It’s a pattern of behaviour that is consistent, if nothing else.

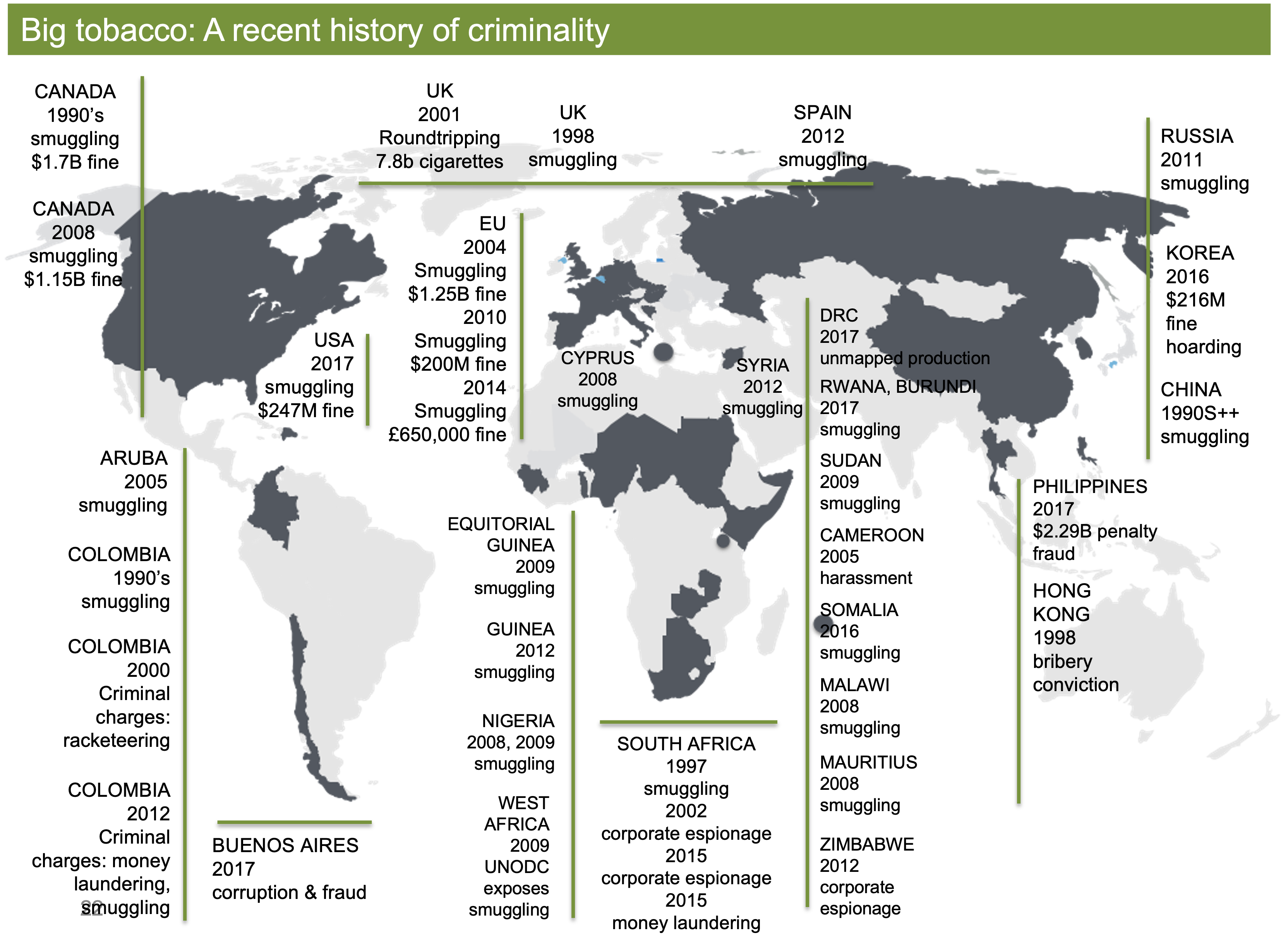

In 2010, British American Tobacco paid the European Commission $200 million to settle “smuggling-related” issues. In 2012, Philip Morris faced an EU lawsuit for “involvement in organised crime in pursuit of a massive, ongoing smuggling scheme”. Also in 2012, it was sued for $3 billion in damages for smuggling, money laundering, conspiracy and racketeering in Colombia; Philip Morris faced a lawsuit in the EU for “involvement in organised crime in pursuit of a massive, ongoing smuggling scheme;” and Canada filed a racketeering and smuggling lawsuit against RJ Reynolds, to the tune of $1 billion. Japan Tobacco was investigated for sanctions-busting deals in Syria. In 2014, British American Tobacco was fined £650,000 for “oversupplying” tobacco in the EU by 240 per cent. (“Oversupplying” is classically the first step in pushing cigarettes into an illicit supply chain, moving from the “oversupplied” market straight into the black market.) In 2017, Philip Morris was criminally charged for alleged fraudulent import practices from the Philippines, facing 272 counts of fraud and a penalty of $2.29 billion; and Philip Morris and British American Tobacco were fined $260 million for illegal cigarette hoarding in Korea – and avoiding taxes on the resulting $178 million profits. And – for good measure – Philip Morris was accused of fraud and corruption in Buenos Aires.

“I believe you are the least credible witnesses that I have ever seen come before the committee of public accounts. You have lied unashamedly. If you did not know all I can say is that you must have been totally incompetent. If I were one of your shareholders I would say, ‘these guys are incompetent.’”

Chairperson of UK Parliamentary Hearings into tobacco smuggling by multinationals

The four big multinationals have faced credible smuggling charges in at least Canada, Aruba, Colombia, the US, Buenos Aires, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea, Nigeria, the DRC, Cyprus, Syria, South Africa, Rwanda, Burundi, Sudan, Cameroon, Somalia, Malawi, Mauritius, Zimbabwe, Philippines, Hong Kong and Russia.

“Management of BAT was aware duty-not-paid cigarettes would ultimately be smuggled in China and other countries. There could be no other explanation for this enormous quantity of duty-not-paid cigarettes worth billions and billions of dollars. BAT’s irresponsible behaviour amounted to assisting criminals in transnational crime.”

Judge Justice Wally Yeung Chun-Kuen

British American Tobacco’s own documents suggest that the company may historically have been involved in smuggling in around 30 countries. BAT’s own managers note how smuggled cigarettes accounted for nearly 30 per cent of BAT’s sales in Canada, and accounts suggest that at one point as much as 25 per cent of BAT’s global profits may have come from selling contraband in China. Multiple sources document their strategies in China, including memorandums that explicitly explain eg, “…alternative routes of distribution of unofficial imports need to be examined.” That is just code for “smuggling.”

5. Big tobacco’s illicit financial flows allow dirty money to seep into the global financial system

As the UN notes, once illegal money has been laundered through the global financial markets – as some 70 per cent of illicit income in fact is – it is much harder to trace its origins.

In the simplest terms, it is virtually impossible to generate illicit income – in this case, from sales on the black market – and not create some kind of illicit financial flow. That income has to be accounted for somewhere, to ensure that the company’s shares remain popular.

In 2012 Philip Morris International was sued for $3 billion in damages for smuggling, money laundering, conspiracy and racketeering in Colombia. Over a period of 10 years, employees laundered drug money as part of a smuggling operation, in the process creating a trail of third-party payments and Swiss bank accounts.

“Defendants created a circuitous and clandestine distribution chain for the sale of cigarettes in order to facilitate smuggling. The decision to establish and maintain this distribution chain was made at the highest executive level of PMI. Defendants have collaborated with smugglers, encouraged smugglers, and sold cigarettes to smugglers, either directly or through intermediaries, while at the same time supporting the smugglers’ sales through the establishment and maintenance of so-called ‘umbrella [cover] operations’ in the target jurisdictions.”

In 2015 British American Tobacco was accused of money laundering in South Africa. It paid a network of undercover agents using Travelex cards registered overseas – but in other people’s names, so that the payments could not be traced. One agent, for instance, received at least £30,500, either in cash or loaded on to Travelex cards registered in the name of a BAT employee in the UK. An information request from HMRC in the UK confirms that the agency identified at least eight South Africans who had a “peculiar relationship with BAT” and received payments from BAT through “concealed transactions.” UK tax authorities described these as an “al-Qaeda-style” method of payment. Correspondence between the agent and BAT shows she became worried about BAT’s surreptitious payment methods. A senior BAT employee assured her that the same method of payment is used by BAT UK around the globe for payment of its other undercover agents.

These illicit financial flows come at a cost – they reduce transparency, making it impossible for our tax administrations to properly assess the taxes due by behemoths like British American Tobacco. But they do more than that: they allow listed companies to engage in purely criminal behaviours.

Conclusion

Big Tobacco’s behaviour is the very definition of “unjust.”

Multinational tobacco companies pose an enormously complex risk – one that includes elements of illicit trade, but one that goes far beyond just that. There is ample evidence of multinational tobacco companies being involved in smuggling their own product. But what lies beneath that is a series of smoke and mirrors that covers how they illegally spy on their competitors, how their structures allow them to pay virtually no corporate income tax, how they inflate sales volumes through fictitious revenue schemes, how they abuse their relationship with tax agencies to secure even more preferential treatment, and how their tax abuse is hardly distinguishable from the criminality perpetrated by organised crime syndicates.

Ultimately, the end result from both their more sophisticated schemes and their dalliances with illicit trade are the same – monies lost to the state, and us as taxpayers having to bear more of the tax burden.

There is something fundamentally unjust about the way in which multinational tobacco companies engage with our tax systems. Complex structures allow them to shift profits and underpay corporate income tax, while opaque supply chains allow them to move billions of cigarettes untaxed. Policies meant to curb tax abuses are diluted and rendered ineffective through relentless lobbying and corruption. Enforcement agencies are coaxed to look the other way with donations of vehicles or are plied with evidence on their smaller competitors, illegally obtained through their corporate espionage programs.

This year on World No Tobacco Day, we say no to multinational tobacco companies shifting obscene amounts of profits. We say no to opaque lobbying and engagements by multinational tobacco companies. We say no to tobacco companies capturing our enforcement agencies. And we say no to opaque supply chains and opaque global financial systems that provide them with an invisibility cloak.

Image credit: Tuxedo Tobacco, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Related articles

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The bitter taste of tax dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Indicator deep dive: ‘patent box regimes’

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations