Rachel Etter-Phoya ■ African countries improve on Financial Secrecy Index, call for UN tax convention to end plunder

African finance ministers have adopted a resolution calling for a United Nations convention to stop tax abuse earlier this week as some of the richest nations, including the US and Switzerland, continue to be the biggest suppliers of financial secrecy according to the Financial Secrecy Index 2022, published this week by the Tax Justice Network.

African countries lose about $90 billion in illicit financial flows each year. This underlines how inadequate rich-countries’ efforts are through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to redesign the rigged financial system. The Financial Secrecy Index 2022 reveals that five G7 countries alone—the US, UK, Japan, Germany and Italy—are responsible for cutting global progress against financial secrecy by more than half.

In the meantime, African economies are dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic’s impact, exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Here in Malawi, the price of bread has more than doubled, now costing over half the minimum daily wage. This is why African leaders this week called for a United Nations Convention on Tax to curb illicit financial flows and recover lost assets, where financial secrecy is an accomplice lurking in the shadows.

In the words of the resolution, endorsed by African finance ministers:

The Conference of Ministers […] Calls upon the United Nations to begin negotiations under its auspices on an international convention on tax matters, with the participation of all States members and relevant stakeholders, aimed at eliminating base erosion, profit shifting, tax evasion, including of capital gains tax, and other tax abuses.

UN Economic and Social Council, Committee of Experts’ Resolutions for consideration by the Conference of Ministers, endorsed 17 May 2022

The African Union and UN Economic Commission for Africa triggered the global adoption of a target to curb illicit flows in 2015. This was through the High-level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, led by former South African president Thabo Mbeki. This paved the way for concerted campaigning by African policy makers, parliamentarians and activists. And the resolution is a testament to their perseverance.

Financial secrecy at large

Financial secrecy is slowly shrinking the world over, despite some of the richest countries subverting progress. Total financial secrecy dropped by 2 per cent in 2022. This follows a 7 per cent reduction in 2020, according to the Financial Secrecy Index 2022. This is because of better international cooperation and more and more countries requiring beneficial ownership disclosure.

Yet the Financial Secrecy Index 2022 remains a warning of the divisive deficiencies in the global financial system. Every country loses. But the impact is hardest for lower income countries (or historically plundered states, as economic anthropologist Jason Hickel has called them).

In the wake of the Pandora Papers—the largest journalistic investigation of the biggest leak exposing the offshore world of finance—journalists Simon Allison and Sipho Kings asked:

What if, instead of giving money to the developing world, rich countries stopped money from leaving the developing world in the first place?

Allison & Kings, October 2021, The Continent

It is sad that some of the largest country donors to Malawi and other African countries are also the greatest enablers of financial secrecy. The United Kingdom, with its spider’s web of Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies like the British Virgin Islands and Guernsey (both ranked in the top 10 in the Financial Secrecy Index 2022), along with other OECD tax havens including the United States and Switzerland, enable individuals to hide and launder money. Multinational companies shift close to 40 per cent of their profits to tax havens. China’s remarkable jump up the ranking from 25 in 2020 to 11 in 2022 is pertinent. China is Africa’s largest trading partner.

Taking on financial secrecy in Africa

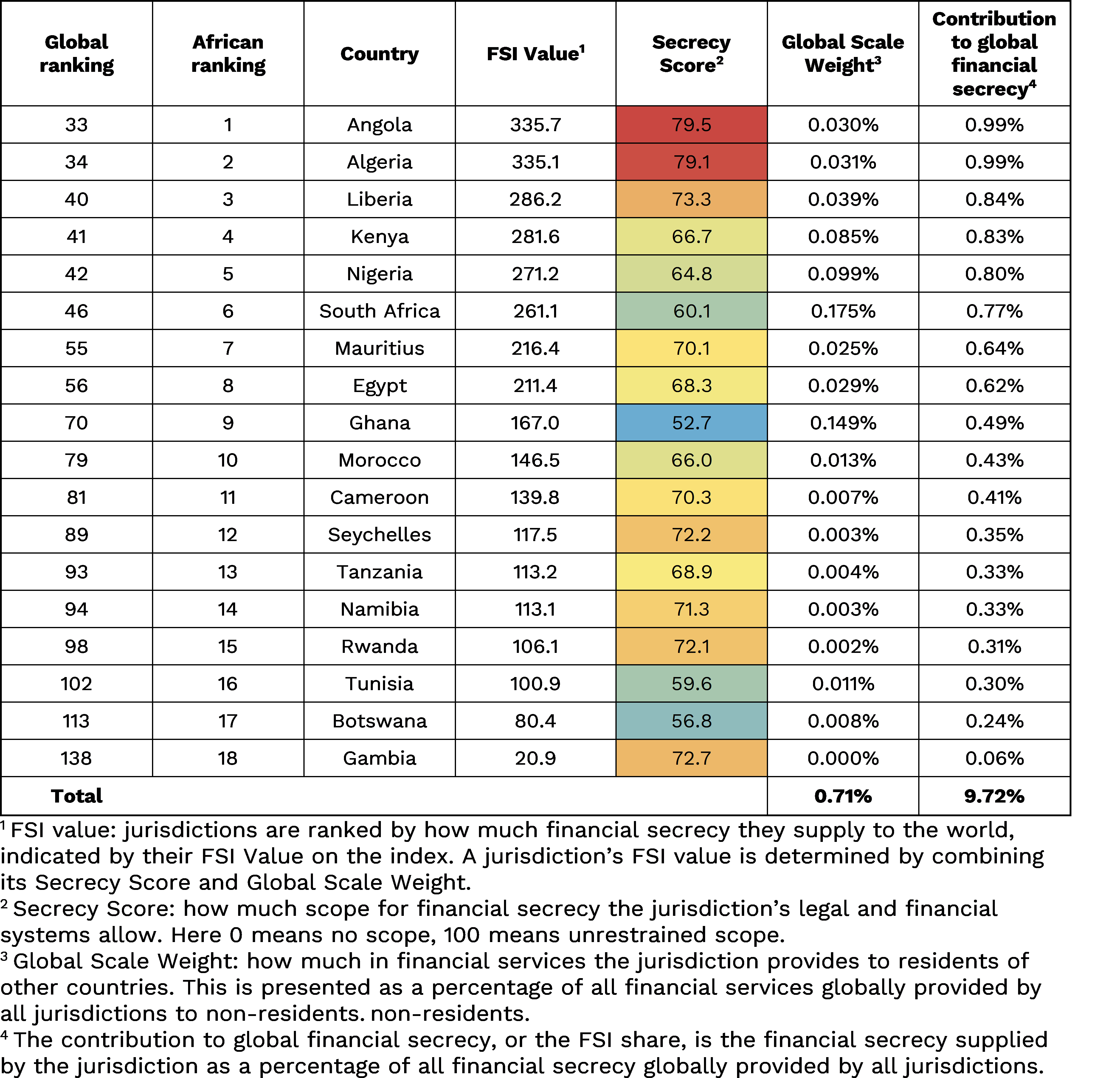

Eighteen of the largest African economies feature in the Financial Secrecy Index 2022.

In the index, countries are assessed on how intensely its financial and legal system allows individuals to hide and launder money. The lower the marks of the secrecy score out of 100 the better. In the index, 100 is full secrecy and 0 is full transparency. The Financial Secrecy Index 2022 analyses financial and legal systems of 141 jurisdictions across four categories. These are: knowledge of beneficial ownership, the transparency requirements for legal entities, the integrity of tax and financial regulation, and international standards and cooperation.

The secrecy score is not just a report card, it’s a problem-solving manual. It shows policymakers the laws and loopholes to amend to become more transparent. But it’s not just how secretive a country is that matters, the index combines the secrecy score with the global scale weight. This is the volume of financial services countries provide to residents of other countries. Services like opening a bank account or setting up a company. The combination of the secrecy score and global scale weight into the FSI value paints a picture of how much offshore financial activity is put at risk by a country’s laws.

Since the 2020 edition of the Financial Secrecy Index, all but four African countries—Rwanda, South Africa, Seychelles and Ghana—have made some progress improving financial secrecy at home. Two countries —Ghana and Liberia—made worryingly large leaps up the index, mainly because they now offer more financial services to non-residents.

Over the last two years, African countries have made steady progress in improving international cooperation on anti-money laundering efforts, information exchange and judicial cooperation. Several tax administrations are improving the way they operate. Half of the African countries also made great leaps in requiring the disclosure of beneficial owners of companies. More than half now have beneficial ownership laws for companies, requiring the real flesh and blood owners to be identified. Yet in most countries limited partnerships remain black boxes, making it possible for the real owners to avoid scrutiny.

All African countries have an alarmingly high secrecy score of over 90 points out of 100 when it comes to the transparency requirements for companies. This is an area with quick wins to stop the bleed. Jurisdictions should require companies to make public up-to-date beneficial and legal ownership information, publish all extractive industries contracts and tax rulings, and let the public have free access to the annual accounts that companies file.

No African jurisdiction requires multinational companies to publish public country by country reports. These reports shed light on where a multinational company books their profits and pays taxes, aiding tax collectors to make sure they are paying their fair share. Yet South Africa and Nigeria are home to some of Africa’s largest multinationals that should require their multinationals to publish these reports.

Taking on financial secrecy inclusively

This week has been monumental with African leaders calling for a UN tax convention because countries, like Malawi, have very little say over the current international tax regime. It has remained substantively unchanged since the early twentieth century. The rule-setter the OECD, has brought 140 countries together in its so-called “Inclusive Framework”, promising an “equal footing” in determining international tax rules. Even the African Tax Administration Forum criticised the pressure African countries were put under in the recent process to develop new tax rules for taxing the digital economy. The Professor of Law Yariv Brauner at the University of Florida has rightly described the forum as a “(not so) Inclusive Framework”, and the emerging reforms it is pushing appear massively favourable to rich countries.

Nigeria and Kenya refused to sign up to the new rules last year. And workers unions and activists across the world took to the streets to protest the “pro-rich and anti-poor tax system”.

Instead of the OECD’s piecemeal approach, a United Nations Framework Convention on Tax, just as the African finance ministers articulated, and a truly representative convening body, where the Malawian and other African governments have a say, are essential to fundamentally change the way all governments can tackle tax abuse. Financing our responses to the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath depend upon it.

Visit the Financial Secrecy Index 2022’s country profile page to understand how each country can tackle financial secrecy. The 18 African countries included are: Algeria, Angola, Botswana, Cameroon, Egypt, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania and Tunisia.

Related articles

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025