John Christensen ■ The Wall Street Climate Consensus

Last week we published the second part of our Tax Justice Focus special on climate crisis and tax justice. This blog reproduces the article contributed by economist Daniela Gabor*, in which she pinpoints the dangers of allowing private actors to take the lead in financing the transition away from fossil fuels to renewables, arguing that private financiers will reap the rewards while passing the risks to states and the general public, and hiding behind ‘subsidised greenwashing’.

Please note that this article was written before the Covid-19 pandemic took off in Europe and North America, precipitating the deepest economic depression in over a century.

Click here to download the first and second parts of our Tax Justice Focus special.

By Daniela Gabor*

The transition to a low carbon economy can be organised in two distinctive ways.

The first way, widely known as the Green New Deal, outlines a radical program of ecological and economic transformation led by the state. This involves massive investments in low-carbon activities – green industrial policies backed by green fiscal and monetary policies – while ensuring that decarbonisation happens in a just manner.

Critically, this calls for demolishing the political order of financial capitalism: undoing its ideological aversion to fiscal activism and state intervention, its commitment to the ‘independence’ of central banks, and to the political power of carbon financiers.

In response, a second, status-quo option is rapidly emerging from the financial sector. Let’s call it the Wall Street Climate Consensus. It promises that, with the right nudging, financial capitalism can deliver a low-carbon transition without radical political or institutional changes.

The WSCC grows out of recent changes in international development discourse, as for instance promoted by the World Bank in its ‘Maximising Finance for Development’ agenda, whose mantra is ‘leveraging private capital for development’. It promises institutional investors $12 trillion in “market opportunities” in transport, infrastructure, health, welfare, and education, to create new investable assets via public-private partnerships in these sectors and deeper local capital markets (or, as the World Bank puts it in a slick video, “to help private finance tap into developing markets.”) They are pushing risky and expensive ‘shadow banking’ practices onto poorer countries, likely to encourage privatisation and usher in long-term austerity, ultimately threatening progress on the SDGs. Under this consensus, nation states are supposed to protect the financial sector from the risks of investing in developing markets. This would privatise gains for finance and push losses onto low-income governments and the poor.

Now, along similar lines, carbon financiers are increasingly seeing the climate crisis not as a threat, but as an opportunity to make high profits, via “subsidised greenwashing.” The idea is that states will subsidise and protect finance from climate risks. This is a great opportunity for finance – and poses great dangers to the wider public and to the climate.

The Wall Street Climate Consensus involves a two-step strategy to promote the creation of apparently ‘green’ asset classes, while also preventing the state from getting too heavily involved in reducing carbon-intensive activities.

Step 1: promote metrics and “taxonomies” to enable greenwashing

The Wall Street Climate Consensus sees it as essential to define metrics and standards that assess the environmental performance of economic activities and companies – and thus of the “green-ness” of loans and securities that finance them. Strategically, they are pushing for public and private taxonomies (classification systems) to allow a broad interpretations of what ‘green’ means.

The most popular approach, pioneered by the private sector, relies on private Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) ratings, to evaluate companies and governments. Private ESG ratings are expanding fast, and are expected to apply to half of some $69 trillion assets managed in the US by 2025[1].

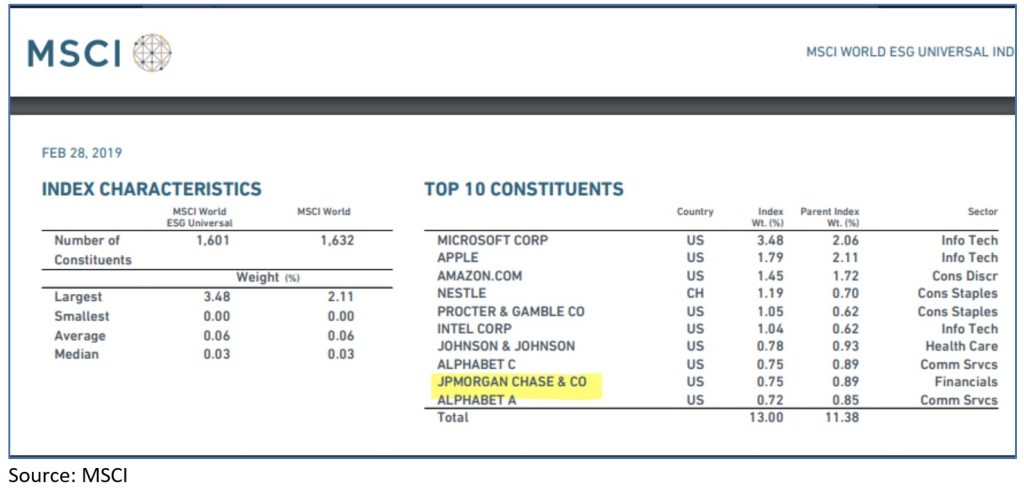

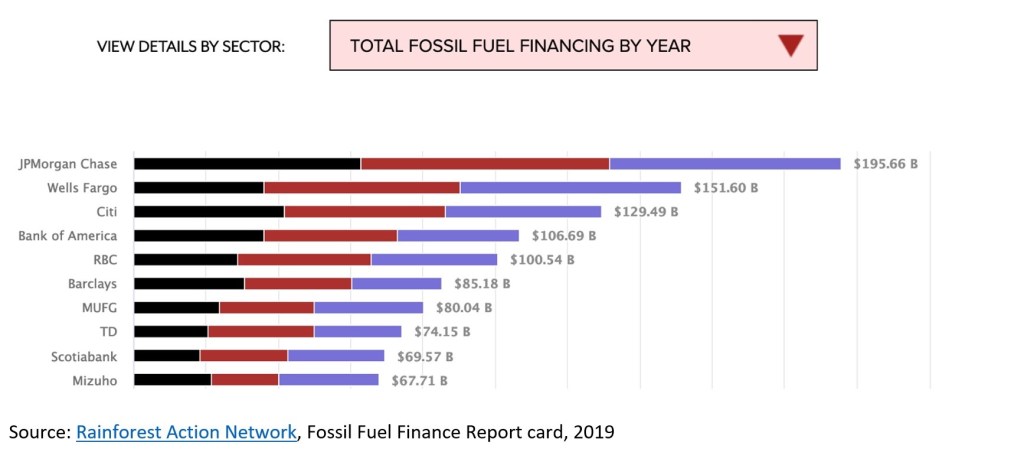

Private ESG frameworks are fertile terrain for greenwashing. For one thing, the various different frameworks offer confusing[2] and conflicting assessments of environmental performance, making it easier for borrowers to mislead investors about the greenness of the assets they purchase. For example, in February 2019 the ESG index run by MSCI, a big ratings agency, contained JP Morgan Chase in its top 10 constituents – in the same year that the bank was ranked (by the Rainforest Action Network) as the biggest financier of fossil fuels.

The multiplicity of private ESG frameworks also allows investors to shop around for the ESG ratings most favourable to themselves – and there is a wide divergence, allowing plenty of choice. (At one point, for instance, the FTSE’s ESG scored the car company Tesla at the bottom of its global auto ESG ratings, while MSCI ranked it as the best.)[3] Making matters worse, ESG rating companies face perverse incentives to award high ratings to firms.

For these reasons public ratings, by contrast, are potentially more effective than private ratings. However, carbon financiers have been successfully lobbying to water down one of the main public classification systems, the European Commission’s Sustainable Finance taxonomy. Originally, it identified “sustainable” economic activities as those that make a substantial contribution to at least one of six environmental objectives, and which cause no significant harm to the others[4], using quantitative thresholds[5]. But after heavy lobbying, the EU taxonomy has now expanded this to three separate categories: sustainable, “enabling”[6] and “transition”[7] activities. The two extra categories are supposed to encourage high-emitting companies to shift from ‘brown’ (polluting) activities to ‘green’ ones, by ensuring that enough financing is available. But in reality they open the door to greenwashing by introducing new complexities in setting and monitoring the quantitative thresholds, and also by restricting the scope for identifying “brown” (or polluting) activities.

Step 2: subsidies for ‘green’ products without penalties for brown

The financiers’ push to shape public and private classifications systems is not only about greenwashing. It is also about boosting profits, by channelling the growing political will to address the climate crisis into subsidies for green assets. For example, the European Commission is considering relaxing capital requirements for financial institutions holding green assets. Central banks, which are pioneers in the policy world in the climate change fight because of the financial-stability implications of extreme climate events, are also considering preferential treatment of green securities in their monetary policy operations (in their so-called ‘collateral frameworks.’). These may turn out to be very expensive for states and the wider public.

This nudging for green finance also seems to be accompanied by a low appetite for targeting ‘brown’ finance, even though penalties (via tougher regulatory requirements or via certain central bank operations) could rapidly accelerate the decarbonisation of the financial system, and shift capital flows away from polluting activities towards greener ones.

The success of carbon financiers in opposing “brown penalties” is partly a result of a long-running de-facto alliance between private financial sector players and central banks. The latter invoke ‘transitions risks’ to justify an incremental, green-subsidising approach, in line with what the Wall Street Climate Consensus wants. When they say ‘transition risks’, what they mean is that strictly regulating and curbing brown finance might result in stranded carbon assets which pose risks to financial stability.

Although central banks do not have the conceptual tools to adequately capture the mechanisms through which transitions risks may morph into financial stability risks, their emphasis on transition risks renders them critical allies for carbon financiers in the construction of the Wall Street Climate Consensus. For instance, Mark Carney’s speech for the COP26 hosted by the UK, and the COP26 private finance strategy, framed in the key of the Wall Street Climate Consensus, envisages a ‘3 R’ approach to leverage private finance for the climate fight: mandatory Reporting of climate risks, nudge private finance to improve climate Risk management via stress tests, and provide a better picture of Return opportunities from the transition to net zero, by moving from problematic ESG approaches to encourage investments in 50 shades of green[8].

While the nods to mandatory reporting and ESG weaknesses are commendable steps forward, the COP26 private finance strategy falls short on the truly transformative measures such as brown penalties or greening the operations of central banks.

Make no mistake: the Wall Street Climate Consensus will not turbocharge the climate agenda. It is designed to protect the status quo of financial globalisation.

Rapid decarbonisation can only happen if central banks and regulators convert to penalising brown rather than subsidising green, and use a credible definition of brown that minimises greenwashing. And states everywhere must take seriously the transformative power of green macroeconomic policies. This involves massive public investments in green sectors financed via ‘green’ coordination between fiscal and monetary policies. It should also include green safety nets to ensure a just transition, one that does not put the burden of decarbonization on the poor.

Furthermore, should governments fail to secure the cooperation of central banks for green macroeconomic policies, they could introduce a Green FTT on brown assets. This would be calibrated to (a) target brown assets and (b) remain in place until an adequately brown-penalising framework is wired into the operations of central banks and broader regulatory frameworks. Together with a carbon tax, this would ensure adequate financing for green public investments while simultaneously re-orient private capital towards private green investments.

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/cad307d6-583a-11ea-a528-dd0f971febbc

[2] Moret, J. (2017). ‘An integrated approach to managing ESG risks and opportunities’, Franklin Templeton, 1 April 2017.

[3] Financial Times (2018). ‘Lies, damned lies and ESG rating methodologies’, 6 December 2018.

[4] These are: Climate Change Mitigation; Climate Change Adaptation; Sustainable Use and Protection of Water and Marine Resources; Transition to a Circular Economy; Pollution Prevention and Control; Protection and Restoration of Biodiversity and Ecosystems. See more https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_19_6793

[5] The Technical Expert Group is in the process of identifying the list of activities and the attending quantitative standards across the six objectives.

[6] Enabling activities are defined as those activities that enable other activities to make a substantial contribution to one or more of the objectives, and where that activity: i) does not lead to a lock-in of assets that undermine long-term environmental goals, considering the economic lifetime of those assets; and ii) has a substantial positive environmental impact based on life-cycle considerations.

[7] Transition activities are defined as those ‘activities for which there are no technologically and economically feasible low-carbon alternatives, but that support the transition to a climate-neutral economy in a manner that is consistent with a pathway to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, for example by phasing out greenhouse gas emissions.’ See https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_19_6804

[8] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2020/the-road-to-glasgow-speech-by-mark-carney.pdf?la=en&hash=DCA8689207770DCBBB179CBADBE3296F7982FDF5

* Daniela Gabor is Professor of Economics and Macro-Finance, Department of Law University of the West of England

Related articles

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Two negotiations, one crisis: COP30 and the UN tax convention must finally speak to each other

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Taxation as Climate Reparations: Who Should Pay for the Crisis?

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition