Andres Knobel ■ Passports and residency for sale: the OECD is sitting on its hands. Here’s how to fix the problem…

Passports and residency issued by many tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions in exchange for money (promoted as “golden visas”), are not only “golden” because they are valuable, but because they are expensive. They aren’t meant for the typical refugee fleeing a civil war, but for the very rich who have no intention of leaving their home, but want to pretend that they have (by using their newly purchased citizenship or residency) to escape from taxes and other laws, if necessary.

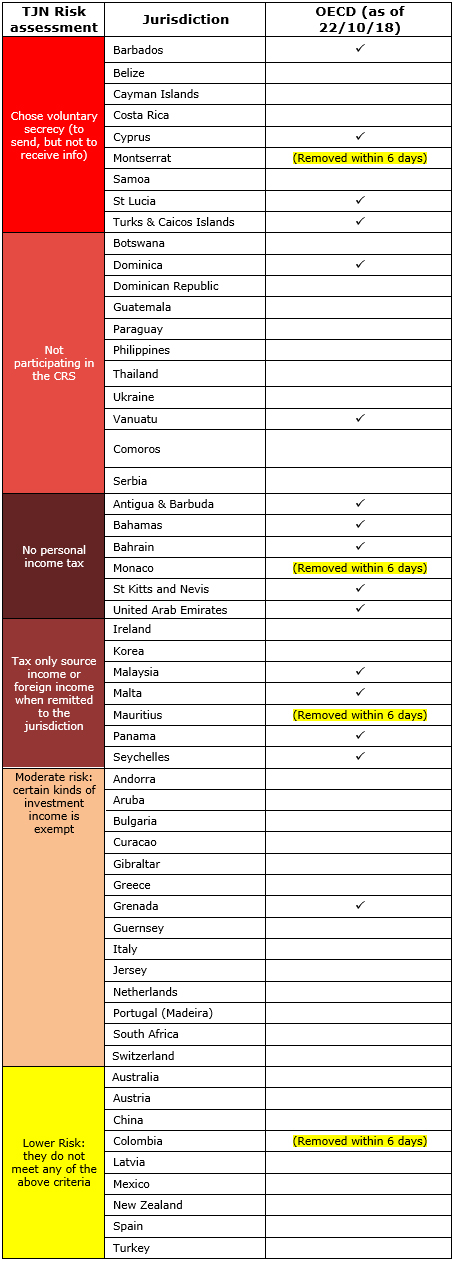

The Tax Justice Network has been warning about the risks of the sale of passports and residency to circumvent automatic exchange of information since 2014. It took four years for the OECD to take this matter seriously and in February of 2018 it opened a consultation about how to address this risk. As a response to this, the Tax Justice Network published a list of 56 risky jurisdictions offering passports and residency in exchange for money, based on the Financial Secrecy Index. Eight months later, on October 16th 2018 the OECD published a list of 21 jurisdictions whose residency and citizenship by investment schemes potentially pose a high-risk to the integrity of the automatic exchange of information. But within six days, four jurisdictions had already been removed from the blacklist, at a pace of one kosher “passport for sale” scheme every 1.5 days. I don’t know how she does it…

We explained in this blog post how residency and citizenship by investment schemes can be used to trick banks into believing that a person resides in some far away tax haven, while in reality they never left their home country. The bank would then (wrongly) report banking information to the tax haven that sold the passport or residency (or worse: the bank may not report any information at all, if that tax haven chose not to receive information under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard [CRS] for automatic exchange of information).

As described by our Bilateral Financial Secrecy Index policy paper, these passports and residencies for sale “create particularly high levels of risks for European tax revenues if they are coupled with an incomplete or low personal income tax system in the jurisdiction offering the schemes, as is the case in the EU for Cyprus, Ireland and Malta, and in Monaco among EU’s associated territories. This combination of lenient rules entices wealthy individuals both from within and outside of the EU to obtain a (fake) residency in such jurisdictions, while continuing to reside, live and work in their original jurisdiction of residency”

In essence, we have three issues with the current OECD’s blacklist for citizenship and residency by investment schemes:

- It doesn’t include all relevant (risky) jurisdictions – just as happens with the EU blacklist

- Countries may easily lobby (or make promises?) in order to be removed from the backlist (four are already gone) – just as happens with the EU blacklist

- Measures to address risks aren’t enough

Here is the actual list of risky jurisdictions according to the Tax Justice Network (ordered by category, highest risk at the top) vs the OECD current blacklist

Not only are there more than 30 jurisdictions, such as Cayman Islands, Belize, Costa Rica or Samoa, missing from the OECD blacklist, but a few correctly blacklisted jurisdictions have already been removed, including Colombia, Mauritius, Monaco and Montserrat. Cyprus is now asking for the same fast route out. Worryingly, the OECD hasn’t published any information about why those jurisdictions were removed from the blacklist.

Source (columns 1 and 2): http://taxjustice.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/20180305_Citizenship-and-Residency-by-Investment-FINAL.pdf; (Column 3): http://www.oecd.org/tax/automatic-exchange/crs-implementation-and-assistance/residence-citizenship-by-investment/

How to address the risk of passports and residency for sale

The OECD is advising banks that, if in doubt about the accuracy and reliability of the declared residency of their account holders, they could ask account holders additional questions including:

- Did you obtain residence rights under an CBI/RBI scheme?

- Do you hold residence rights in any other jurisdiction(s)?

- Have you spent more than 90 days in any other jurisdiction(s) during the previous year?

- In which jurisdiction(s) have you filed personal income tax returns during the previous year?

In addition to these questions, the Tax Justice Network’s brief and the Financial Transparency Coalition’s submission in response to the OECD consultation proposed the following measures for banks and other institutions when determining their account holders’ real residency:

- Require all previous residencies and citizenships;

- Require a copy of the birth certificate (to see if the declared residency/citizenship matches that of the place of birth), and citizenship of parents;

- Require test of proficiency in the language of the declared residency/citizenship;

- Require proof of stay in the country of the declared residency, e.g. passport stamps showing presence in the country, attendance by children to a local school, groceries and other basic consumption throughout the year, etc.

In essence, banks should determine an individual’s “centre of vital interests”, rather than ask to see a passport and a utility bill that may be all too easy for a rich person to ‘fake’. The passport and utility bill may be ‘real’, but they can mislead in terms of where the rich individual actually resides, meaning where their centre of vital interests actually is: their friends, family, personal and economic relations, cultural and political activities, etc.

In addition, we have been asking for countries issuing passports or residency in exchange for money, to publish a list of all individuals who acquired these schemes, or at least to share their identities with the country of their previous (and very likely real) residence or citizenship.

Since then, we have heard of new ideas (thanks to Mark Morris and Christoph Trautvetter) that could also help:

Spontaneous exchange of banking information with the country of the past residency/citizenship.

Imagine Otto Müller, a German resident, acquires a residency certificate from St. Kitts and then opens a bank account in St. Kitts and one in Switzerland using the St. Kitts residency. Even if St. Kitts informs Germany that Otto acquired the residency certificate, how would the local banks and the Swiss bank know that Otto is potentially still resident in Germany so that his information is also sent to Germany?

In order to address this, St. Kitts, just like any other country selling passports and residency, should not only inform the former country about the acquisition of the passport/residency, but they should also forward any banking information that they received about the individual who acquired the passport or residency. In the above example, if St. Kitts receives information about Otto’s Swiss bank account, it should forward that information to Germany.

For example, it appears that Monaco was removed from the blacklist because it exchanges information about the individuals who apply to Monaco’s scheme with all existing countries of residency. The above proposal entails Monaco not only telling countries about the applicants’ identity, but also forwarding the banking information it receives about those applicants, to the past countries of residency.

Publishing a list of current taxpayers

Another idea is for tax authorities, all over the world, to publish a list of their taxpayers. This information is already public in some countries (e.g. in Argentina it’s possible to find a person’s tax identification number and status just by googling their name). Even for countries with high fiscal secrecy, this list could even be confidential and available only to financial institutions (after all, it’s in the interest of each tax authority to make sure that any current taxpayer accurately informs their bank about their tax residency). Nevertheless, there could be issues if a taxpayer changed their name in the passport, or if there are too many people with the same name. By adding for example the date of birth, the likelihood of two or more Otto Müllers born on the same date would be reduced.

An alternative to this would be for countries selling passports and residencies to publish the list of individuals who acquired them, and then banks could simply check if any of their account holders share the same name with anyone on that list. If many people with the same name are matched, additional details such as date of birth could be investigated in order to determine which one acquired the passport or residency.

Automatic exchange statistics

The only problem with all of the above proposals is that they depend on the actual banks and tax havens to publish names or do proper due diligence, when in fact these banks or tax havens may be deliberately trying to help individuals hide their money.

For this reason, the real solution to complement the above (and to identify other avoidance schemes) is to have public statistics about automatic exchange of information, as we have been calling also for years here, here and here.

How would statistics not suffer from the same deliberate wrongful reporting by banks and tax havens?

First, faking statistics that have to be reported and checked by the Central Bank and other international institutions, e.g. the Bank of International Settlements, may be different than a bank employee simply failing to ask all the relevant questions and proof to determine an account holder’s real residency.

Second, it’s not necessarily the same countries that would be doing the reporting. No matter how many shady attempts a person may make to try to keep their identity (or residency) hidden, everyone wants their money and assets to be safe. So, while someone may happily acquire a residency from a remote place, like St. Kitts or Vanuatu, their money will probably stay in safe places like the US, Switzerland, the UK or Germany. These major financial centres should be publishing automatic exchange statistics, or at least financial information statistics.

For example, the US and Switzerland should publish statistics on bank deposits including country of residence of the beneficial owner of the account. This is how avoidance schemes could be exposed. If deposits held by residents from Latin America and African countries in the US and Switzerland decreased after 2014, while deposits by residents in Vanuatu increased in parallel, then one could investigate further because it seems that residents from these Latin American and African countries are using residencies from Vanuatu to hold their bank accounts.

Even if such shifts from one country to another isn’t visible, the absolute number may be relevant. If public statistics showed that residents from Vanuatu hold billions of dollars in deposits in the US and Switzerland, while the population of Vanuatu (or their number of billionaires) is quite low, one could also guess that the residency by investment scheme from Vanuatu is being abused.

Statistics, in other words an aggregate amount of the actual data or facts, is the best way to ensure that banks and tax havens are complying with automatic exchange of information.

We have already shown examples of how this could be used here (using total liabilities by country of origin published by the US and Switzerland). Now more countries are starting to publish statistical information about automatic exchange of information. They just need to include more details to become actually useful.

For example, Argentina and Japan published information about the number of accounts they received pursuant to automatic exchange of information, and where their residents were holding most of their money. We are hoping Australia will lead by example.

Related articles

UN tax convention hub – updates & resources

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The bitter taste of tax dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

Taxing windfall profits in the energy sector

14 January 2026