Alex Cobham ■ Progress on global profit shifting: no more hiding for jurisdictions that sell profit shifting at the expense of others

![Cobham Jansky 2017 WIDER 2[3]](https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/fly-images/3408/Cobham-Jansky-2017-WIDER-23-1-1400x600-c.png)

The world’s largest economic actors are also the least transparent. Multinational companies and their big four advisers have been so effective in lobbying for opacity that their reporting requirements are actually less than is required from even small and medium-sized, purely domestic businesses. But change is coming…

The OECD has confirmed today that from late 2019 it will start publishing aggregate and anonymised data from the country-by-country reporting of multinational companies. The exact quality of the data remains to be seen, but this does seem to represent a massive step forward in global corporate disclosure – and is likely to be the best we’ll get until companies are required to publish their own reporting. [The OECD has always been against making individual companies’ country-by-country reporting data public; and the EU’s proposals for public reporting may unfortunately not happen for the moment anyway, as we covered here recently.]

And while the aggregate data will still allow individual multinationals to hide all sorts of things, it does have the potential to support powerful progress towards accountability for corporate tax havens that leech revenues from lower-income countries all over the world – undermining commitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The opacity of profit shifting by multinationals

While there are reasons to be cautious about comparing the revenues of individual governments and the turnover of individual companies, it is nonetheless striking that on this basis, 69 of the largest 100 economic entities in the world are companies rather than governments. And this is all the more striking when we consider how much information each is required to publish on their activities. Governments have greater responsibilities to citizens than do companies to their various stakeholders, perhaps, but not to the extent of the discrepancy in data disclosures.

For example, we know the line-by-line breakdown of government revenues. But for most multinationals, we don’t even know the level of sales in different countries. Or of staff. Or assets. Or profits. Or tax paid. Or all the companies or names under which a multinational operates…

Consider instead, a company operating in a single jurisdiction – as was the case for all companies at the time when corporate law and accounting norms began to emerge, with rare exceptions like the East India Company and Royal Niger Company operating on behalf of imperial powers. For single-jurisdiction companies, most of this information is contained in the annual accounts. And those annual accounts, in many jurisdictions, have long been required to be placed in the public domain.

This reflects a crucial decision in the development of entrepreneurship, by which governments allowed the liability of those running companies to be capped – so that commercial activity was not held back, for example, by the risk that business failure would also mean the loss of one’s family home. While having sporadic use across millennia, it was only from the early 19th century that limited liability companies were the subject of formal legislation, followed by widespread use.

The effective quid pro quo for this protection was the publication of company accounts, signed off by an approved auditor. Limited liability socialises (some of) the private risks of business failure. The publication of audited accounts, in exchange, provides transparency to allow external stakeholders and investors to manage their own exposure to those risks.

In the 20th century, the growing emergence of business groups operating trans-nationally necessitated major changes to national regulatory frameworks that had hitherto been purely domestically focused. Most obviously, this process saw the League of Nations take a leading role in establishing the basis for international tax rules that first governed the imperial interactions in the multinational tax sphere, and were later taken up by the OECD.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, compared to tax, there was less pressure to ensure transparency regulations were adapted for the globalising world. With most multinationals headquartered in, and owned from current or former imperial powers, these OECD country governments were largely confident in their ability to ensure domestic regulatory compliance and to access any data they required to ensure appropriate tax was paid – in their own jurisdictions.

Cracks in the wall

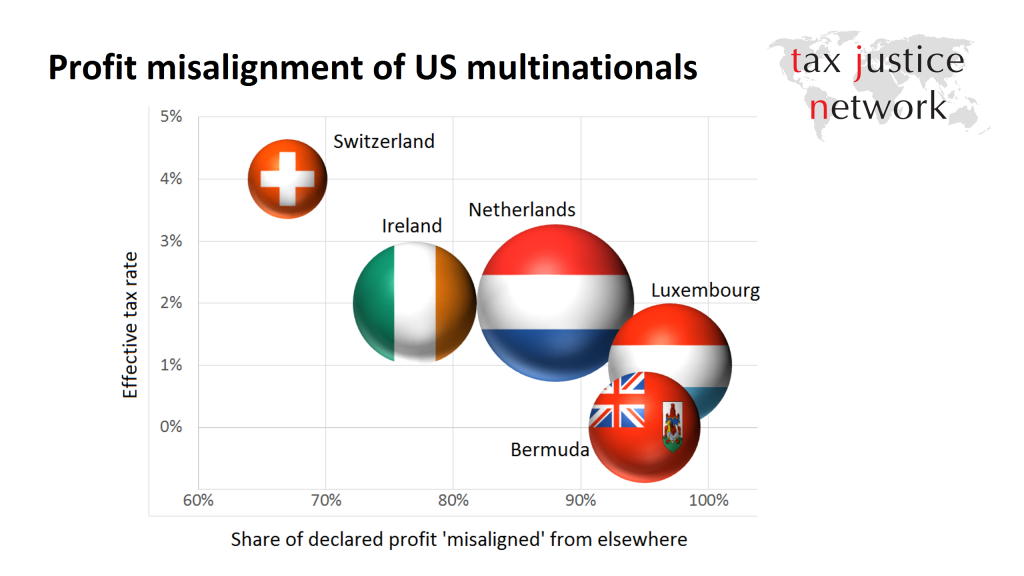

As we have documented (Cobham & Jansky, 2017) for US multinationals, the real explosion in profit shifting began in the 1990s. At this point, a ‘mere’ 5-10% of global profits were declared away from the jurisdictions of the underlying real economic activity. By the early 2010s, that had soared to 25-30% of global profits, with an estimated revenue loss of around $130 billion a year – broadly in line with estimates of around $500 billion in revenue losses from the profit shifting of all multinationals. – And just a handful of jurisdictions offering near-zero effective tax rates and benefiting at the expense of all others. Following the financial crisis of the 2008-9, OECD countries and their publics felt, for the first time, some of the anger at these revenue losses that policymakers in lower-income countries had long known. In 2012, the G20 group of countries gave the OECD the mandate to start work on reforming their international tax rules, and from 2013-2015 the BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) Action Plan was rolled out.

Following the financial crisis of the 2008-9, OECD countries and their publics felt, for the first time, some of the anger at these revenue losses that policymakers in lower-income countries had long known. In 2012, the G20 group of countries gave the OECD the mandate to start work on reforming their international tax rules, and from 2013-2015 the BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) Action Plan was rolled out.

Among reforms that were largely seen as ineffectual, the OECD also introduced – at the specific direction of the G20 and G8 groups – a standard for country-by-country reporting, closely based on the original Tax Justice Network proposals.

Although this momentous shift in corporate disclosure was deliberately hamstrung by requiring that only home tax authorities would receive the data, and share it with their counterparts elsewhere under strict confidentiality criteria, the specious arguments about compliance costs were eliminated at a stroke. Now individual champions such as Vodafone have committed to publish their OECD standard reporting (from next year), and the EU is considering requiring all such reporting to be made public.

Today’s announcement

In the meantime, however, the OECD has now obtained agreement from the BEPS Inclusive Framework members to collate and publish aggregate and anonymised country-by-country reporting data. After a technical design process in which the Tax Justice Network was happy to participate, the OECD has today published the outline of what will be published – and it represents a major step forward.

While individual multinationals’ data will remain confidential, (which we oppose), the country-level aggregation will mean that for the first time, we will have public information on the scale and distribution of declared profits and taxes paid, as compared with the location of real economic activity. There will be no more hiding for the jurisdictions that procure profit shifting at the expense of all others.

And on top of this, the aggregate data if of sufficiently high quality will provide the basis for a proposed indicator in the UN Sustainable Development Goals framework, to capture the profit shifting component of the illicit financial flows that pose such a threat to development.

This is one of those technical moments that are politically significant. Below we reproduce in full Annex C of the OECD Secretary-General’s report to the G20 finance ministers, where this technical moment was first made public.

Annex C. Using Country-by-Country Reporting Data

to Measure BEPS

118. The collection of aggregated and anonymised data from the Country-by-Country

Reports (CbCRs) was a key recommendation of the BEPS Action 11 final report and

will play an important role in supporting the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework’s

ongoing work on the measurement and monitoring of BEPS. The aim of collecting these

data is to provide governments with a more complete view of the global activities of the

largest MNEs and to improve the analysis of BEPS and the effect of BEPS

countermeasures in conjunction with other data available to governments. At present,

one of the major challenges associated with measuring BEPS is that only limited

information is available on the location of MNE groups’ income, taxes, and business

activities CbCRs represent a step forward in supporting the measurement of BEPS since

they will provide jurisdiction-specific information.

119. CbCRs provide information on income, taxes, and business activities of MNEs

on a tax jurisdiction-by-tax jurisdiction basis. This is very important information for tax

administrations in order to assess high-level transfer pricing and other BEPS-related

risks of specific MNEs. It may also be a valuable source of information that can

contribute to the measurement and monitoring of BEPS at a macro level. Consequently,

the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework members have agreed to provide three main data

tables summarising the information reported on CbCRs according to the jurisdictions

where MNEs operate and the tax rates faced by MNEs.

Table 1: Where do the business activities of MNEs take place?

120. The first table to be provided by the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework members

will include an overview of MNE activities based on the jurisdictions of their operations.

It will contain aggregated tabulations of the data provided on CbCRs grouped by the

jurisdictions reported on the CbCRs. Stateless entities will be considered as a separate

jurisdiction though there will be variation across jurisdictions as to which entities are

considered stateless. For each jurisdiction, the total of each of the variables (i.e., income,

taxes and business activities) pertaining to that jurisdiction on all CbCRs filed will be

reported. Two separate panels will be reported for this table: one panel that contains

only data from jurisdictions where MNE groups have reported positive profits, and one

panel that contains only data from jurisdictions where MNE groups have reported losses.

This will be important for the calculation of tax rates and to provide an overview of the

geographic distribution of profits and losses. If necessary to preserve the confidentiality

of the data, OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework members can aggregate jurisdictions for

which information cannot be released individually into broad geographic groupings.

Table 2: What are the tax rates paid by MNEs?

121. The second table will provide an overview of MNE activities based on the tax

rate faced by MNEs. MNEs will be categorised according to the overall tax rate they

face, and MNEs with total profits that are negative or zero will be included in a separate

category. For each category of MNEs, the total of each of the variables recorded on the

CbCRs filed by the MNEs in that category will be reported. Within each category of

MNE, information will also be broken down at the jurisdiction level. The OECD/G20

Inclusive Framework members may aggregate jurisdictions into geographic groupings

where this is necessary to preserve the confidentiality of the data.

Table 3: What is the relationship between tax rates and the business activities of MNEs?

122. The third table will provide an overview of MNE activities based on the tax rate

faced by MNEs in the jurisdictions where they operate. In order to create this table, a

tax rate will first be calculated for operations in each jurisdiction listed on an MNE

group’s CbCR. That is, for each MNE, jurisdiction-specific tax rates will be calculated.

The operations in each jurisdiction will then be categorised according to their tax rate.

In Table 3, the total of each of the variables recorded on CbCRs will be reported broken

down by this tax rate category. In this table, no jurisdictions will be specifically listed

by name.

123. After these data tables are prepared, the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework

members have agreed that ratios can be computed from the variables reported on the

tables to examine the relationships among MNEs’ income, taxes, and business activities.

These ratios will be grouped into three categories. The first category will include

measures of tax burden, such as the ratio of income tax to profits and the ratio of income

tax to total revenues. The second category will include measures of profits relative to

economic activity, such as the ratio of profits to total revenue and profits to the number

of employees. The third category will contain other measures, such as the ratio of related

party revenues to total revenues.

Preserving the Confidentiality of CbCRs

124. CbCRs contain confidential information regarding MNEs, and preserving the

confidentiality of this information and the anonymity of MNE groups reporting this

information will be of paramount importance. In order to preserve the confidentiality of

individual CbCRs, governments will perform the analyses and then provide the

aggregated and anonymised data to the OECD. Governments will only provide these

analyses for CbCRs filed directly in their jurisdictions in order to avoid disclosing any

information from CbCRs obtained through exchange agreements. It will be critical that

these analyses be performed and presented by OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework

members in as consistent a way as possible in order to improve comparability of the

data and to facilitate the study of BEPS behaviour. Some flexibility in the level of

aggregation is provided to ensure that the reported statistics are anonymised and

preserve the confidentiality of the filing taxpayers.

Monitoring BEPS through CbCR Data

125. By gathering and publishing these aggregated analyses, governments and the

public will have an overview of global MNE activity that was not be available otherwise.

The aggregated analyses of CbCR data may provide indications of the extent of the

misalignment of taxes, income, and business activity. However, it is important to note,

that due to the aggregated nature of the CbCR analyses and the limited number of items

on the CbCR itself, definitive conclusions about BEPS will not be able to be drawn from

the analyses alone. The analyses will be made publicly available.

Related articles

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

The State of Tax Justice 2025

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

Bad Medicine: A Clear Prescription = tax transparency

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Lessons from Australia: Let the sunshine in!

Strengthening Africa’s tax governance: reflections on the Lusaka country by country reporting workshop