Nick Shaxson ■ Switzerland is handing back looted money. How big a deal is this?

In the context of a fun Twitter fight and finger-pointing between the Swiss Bankers’ Association and the German Finance Ministry, there’s a newish story on Quartz entitled Swiss bankers swear they are trying to help Africa get its dirty money back. It begins like this:

“It irritates Valentin Zellweger that ‘no longer than six minutes into any James Bond movie, a sleazy Swiss banker still appears.’ “

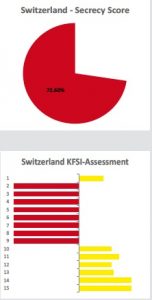

This is, of course, the story that Switzerland, which is still ranked top of our last Financial Secrecy Index, has not only made *some* improvements to its egregious and globe-harming secrecy regime, but it is engaged in a furious domestic and international public-relations exercise to try and distance itself from a deeply criminal past. Nobody should ever forget Swiss bankers’ efforts to use deception, fraud and other tricks to hang onto assets belonging to the families of Jews murdered by Hitler’s regime, before being dragged into making some amends by global outrage. And as if that weren’t bad enough, there’s oceans of other murderous and criminal stuff that we shouldn’t forget either.

Well, the Quartz article continues:

“That stereotype is now something of an anachronism, insists Zellweger, director general of public international law and legal Advisor of the Swiss foreign ministry. He says his country is now indeed at the forefront of international efforts to recover and return such loot, and to cast light into its bank vaults.”

So: is he right? Just how far has Switzerland gone with its clean-up?

The short answer is: Switzerland has improved – but from an appallingly low level: a level so low that it requires extraordinary, life-altering efforts to change, if it wants to be considered part of the community of responsible nations. Its efforts have fallen far short of what’s required, and it is continuing to create new secrecy schemes, even after all the deserved opprobrium of recent years.

The longer answer is as follows.

This particular Quartz story deals mainly with the question of “restitution” – that is, when potentates and their cronies loot countries and stash their winnings offshore, can those countries get that looted wealth back, once those rogues are deposed?

It’s not a straightforward thing, in fact. You can’t just clear out a bunch of bank accounts and shell companies and return it to the victim country, without going through a lot of legal checks and balances first. And:

“Zellweger said they were helpless without the legal cooperation of the governments in the countries where the money came from. Which was not always forthcoming, surprisingly.”

Quite often, the wealthy élites that enriched themselves don’t just go away: they hang around and stay influential. For example:

“The two Kabila administrations in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) had given Switzerland zero cooperation in recovering Mobutu Sese Seko’s millions. The reason was that Mobutu’s eldest son—and heir—François-Joseph Mobutu Nzanga Ngbangawe had become deputy prime minister. He blocked the release of the money to the DRC state.”

So far, so fair enough. And in fact, it is true to say that Switzerland has been better than other jurisdictions in getting stolen money returned: most famously with funds looted by crooked Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha. A Swissinfo tally from March states:

2002: $77m looted by the former spy chief Vladimir Montesinos is returned to Peru.

2003: The return to the Philippines of $600m looted by former President Ferdinand Marcos

2004-2009: Swiss return $700m in Abacha money to Nigeria. Under an agreement in March this year, Geneva prosecutor announces the return of a further $380m to Nigeria, from accounts in Luxembourg (yes, them again.)

2007: Switzerland starts returning funds to Kazakhstan. By last December, $115m had been returned.

2008: Switzerland returns $84m looted by Raul Salinas, brother of former president Carlos Salinas, to Mexico.

2012: Switzerland announces the return of $43 million to Angola. It isn’t clear if the money has been returned yet.

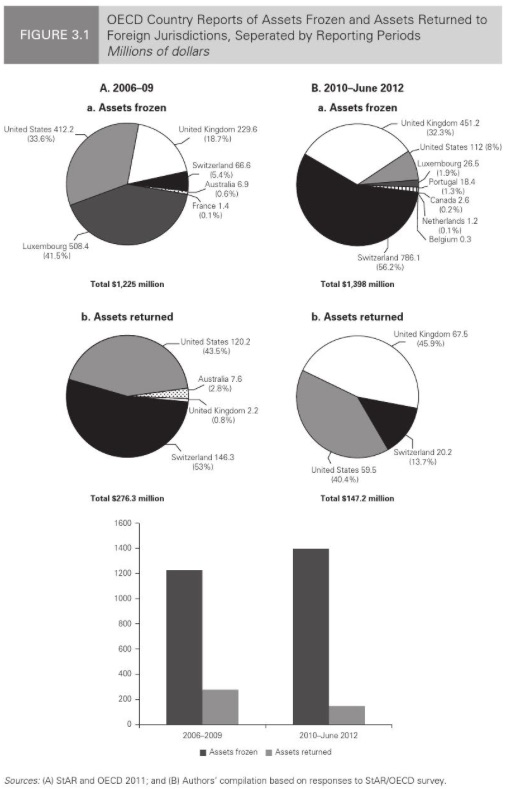

A bunch of other assets have been frozen, but not yet restituted. The grand total here is around US$1.6 billion. This is a hefty slice of the world total, as the World Bank’s STAR (Stolen Asset Recovery) programme estimated in 2014:

(This graph underlines a point in that Twitter fight we mentioned: where on earth is Germany, whose tax-exempt $2.5-3 trillion in non-resident assets make it a big player in this game.)

The Quartz story, which was written based on a speech by Zellweger at the South African Institute of International Affairs, fingered not just the United States as a key (and hypocritical) player in the game – which we’d roundly agree with – but also Dubai, which we have also identified as an especially nasty secrecy jurisdiction:

“Lewis [head of the South African NGO, Corruption Watch] fingered Dubai as one of those still highly secretive new financial centres that Zellweger said now needed to join the move to greater banking transparency. Lewis predicted that the many unexplained recent visits there by members of the South African government and its associates would eventually reveal something nefarious. ‘It if walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it probably is a duck,’ he said.”

And now the ‘buts’ . . .

. . . and they are big ‘buts.’

Though Switzerland is has led the way on the narrow question of restitution, there is now a long list of ‘buts.’

First, this figure for $1.6 billion in restituted funds isn’t an annual figure: it’s a total figure over history. Given that Thabo Mbeki’s High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows estimated that illicit financial flows out of Africa could be running at $50 billion per annum, this is small beer, especially given Switzerland’s historically central role in this dirty picture.

Second, ‘restituted funds’ is just one aspect of the “Swiss problem.” As we noted only a few days ago, Switzerland has aggressively been creating new secrecy facilities, in league with offshore interests in Luxembourg (as ever) and the United States. This is a big new problem, with Switzerland — to be precise, the Swiss government — among the most egregious players in this respect. This is a big, bad new story.

Third, Swiss banking secrecy is alive and well. Originally underpinned by the Swiss banking secrecy law of 1934, this law continues to be a foundation of the Swiss financial centre. Until they fully repeal this law, their claims to have cleaned up are bogus. And even then, take a look at the many ways in which Switzerland – beyond plain-vanilla banking secrecy – isn’t up to scratch.

Fourth, as we never tire of reminding people, Switzerland continues to make bilateral concessions to powerful countries that threaten their banking sector – most notably the United States – but they make very few concessions to weak, vulnerable countries that are the greatest victims of this looting — and when they do make (often limited) concessions on secrecy, they often force aggressive tax or other concessions out of them in return. It is what Andreas Missbach of Alliance Sud has called the “Zebra strategy” – white money for neighbouring or powerful countries, and black money for developing countries.

Fifth. Switzerland is continuing to this present day demanding — can you believe this? – that victim countries give their criminal élites amnesties before they will deign to exchange information with them. Criminal states leopards don’t change their spots easily, it seems.

Sixth. And this is a tax haven classic. Switzerland continues to persecute financial secrecy whistleblowers, and has corrupted its courts (if you don’t believe us, look at the underlying evidence here) to achieve the desired level of persecution. The whistleblower Rudolf Elmer, in fact, goes to court again in two new trials: one on June 23rd, and one on June 24th.

Save the date.

Read more about how Switzerland became (and remains) a secrecy jurisdiction, here.

Related articles

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition