Nick Shaxson ■ Colombia and civil war: the role of tax

A guest blog By Thomas Mortensen, with thanks. A bilateral ceasefire is due in Colombia in the coming weeks, hopefully December 16th.

Tax is not the most obvious remedy for civil war but in the case of Colombia, it could go a long way. The country has suffered an internal armed conflict for more than 50 years, which has left 7 million victims. One of the underlying causes of the war is economic inequality. Colombia is the most unequal country in Latin America and tenth in the world[1]. One of the reasons for this is that Colombia’s fiscal system has completely failed to reduce inequality.

In part this is because monetary transfers and especially pensions benefit the middle and upper classes rather than the poorest people. In addition, high indirect taxes hit the poorest hardest while capital gains – the province of wealthy people – are largely tax-exempt.

So much for Colombia’s regressive tax system. On the government spending side, peace building costs money. A report this year by the Bank of America and Merrill Lynch[2] estimated those costs at between 1.1 – 3.8 % of GDP[3].

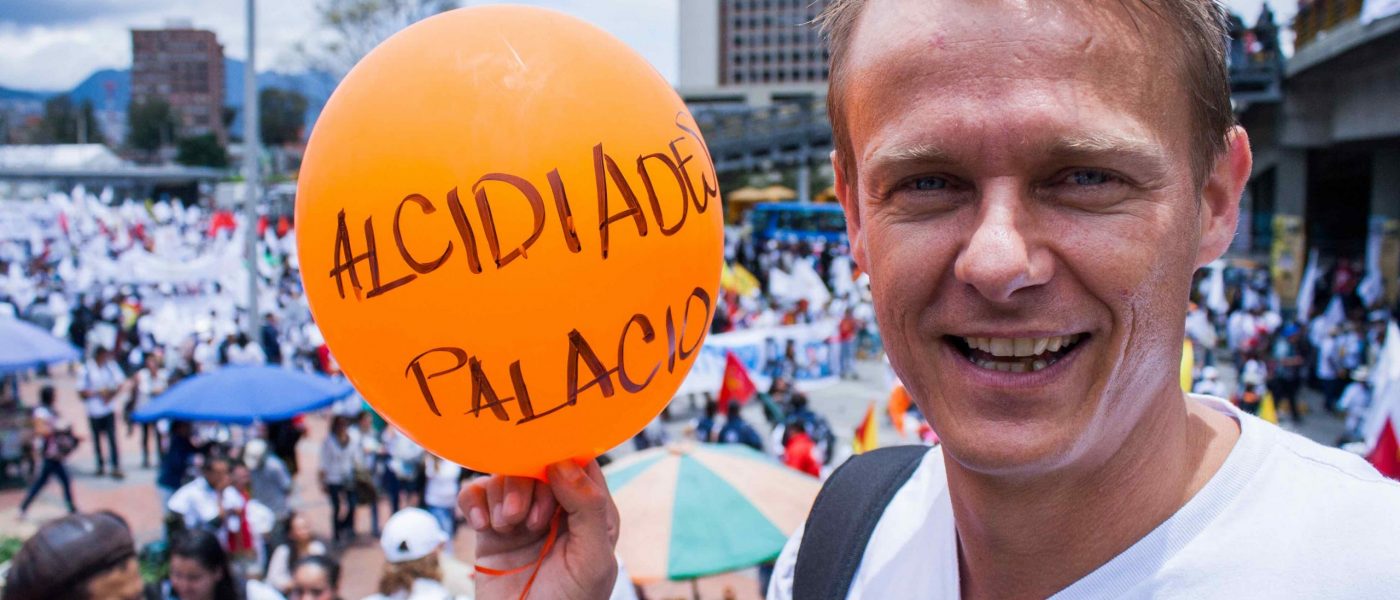

Community members from Buenos Aires. Families here have been repeatedly removed from the land which traditionally has provided enough food for their subsistence. Christian Aid / Federico Rios

The good news is that a lot of the “costs” associated with peace are ones that the state should be paying anyway. There is a lot of public debate about these costs but it could actually be a red herring in the sense that with or without a peace agreement, overall tax revenues from the more affluent sectors of society need to increase. This is in order to support public services and especially to enable the state to guarantee the constitutional rights of its citizens, especially women, and marginalised and rural afro, indigenous and peasant communities.

The costs associated with peace include, for instance, those of creating civilian authorities in rural areas, providing basic services and security to the population and enabling victims of the conflict to return to places they have fled.

A further incremental cost of peace building is that of demobilising and integrating former insurgents – but these are not especially high. For example, if 12,000 combatants demobilise[4], it would cost around US$156 million over six years, which is relatively insignificant compared to an estimate of the total cost of peace, of somewhere between US$5,300 million and US$18,000 million over 10 years. These relatively insignificant costs of demobilising and reintegrating ex-combatants from the guerrilla should be held against the enormous costs of maintaining a combined police and military force of almost 500.000 people. At least in the medium to long run these costs can be reduced substantially.

Taxes are also linked to peace in the sense that inequality must be addressed to ensure that the peace agreement is sustainable and leads to a far less violent society. There is an important lesson learned from Guatemala, where progressive tax reform was included in the peace agreement but never implemented. This failure to address the country’s extreme level of inequality is one of the main reasons why this country today is facing extreme levels of violence, even in the absence of formal war.

Academic literature on peace distinguishes between negative peace and positive peace. Negative peace is simply the absence of violence, while positive peace refers to the capacity of a society to fulfil the rights of its all citizens and reduce grievances and resolve remaining disagreements without the use of violence.

An equal distribution of resources is essential for positive peace because fulfilling the rights of all citizens is evidently easier in a society with an equal distribution of resources.

Likewise, grievances are reduced in a society with an equal distribution of resources. It is no coincidence that Latin America and the Caribbean is both the most violent region and the most unequal in the world.

Regarding how to redistribute resources via the tax system to address the concentration of wealth head on, and enable the region to finance its development comprehensively, the Colombian Tax Justice Network, supported by Christian Aid, has a number of well-documented proposals:

- The tax structure should be based on the principle of progressivity, relying more on direct taxes and less on indirect taxes, which affect the poorest most. Direct taxes should also address the high concentration of wealth, with taxation of assets (land, real estate) and capital gains. Taxing the rich properly would be by far the fairest and most effective way to increase tax revenues.

- The Government should publish all tax exemptions and start working towards removal of discretionary exemptions and incentives. The many tax exemptions benefiting the corporate sector, in particular, the financial sector and the extractive industries should be cancelled. These sectors are hugely profitable in Colombia, even without tax incentives.

- Concrete measures should be taken to make the system more transparent and able to prevent tax evasion including that through tax havens such as Panama [TJN adds: see our recent Panama country report.]

- Indirect taxes, which are regressive in nature but a very important source of tax revenue in Colombia, as in other Latin American and Caribbean countries, should be adjusted so that luxury items are taxed more heavily while basic household items are taxed less.

- Also, increased regional cooperation is necessary to work towards tax harmonisation and against tax competition and the race to the bottom.

- At a global level, increased cooperation is needed to tackle cross-border tax evasion through automatic exchange of tax information and a crack-down on financial secrecy and tax havens, as well as corporate transparency reforms such as public country-by-country reporting.

By Thomas Mortensen, Country Manager for Christian Aid in Colombia

Notes:

[1] Pobreza Monetaria y Multidimensional 2013, DANE (2014)

[2] Análisis de los costos y beneficios del acuerdo por el proceso de paz en Colombia, Francisco Rodríguez, Economista Sénior de la Región Andina, Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Research.

[3] Cuánto cuesta, cómo se paga y qué se puede ganar con una eventual paz en Colombia, BBC, July 20, 2015

[4] FARC has around 7,500 to 9,000 combatants and ELN a few thousands, according to most estimates.

Related articles

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The myth-buster’s guide to the “millionaire exodus” scare story

Money can’t buy health, but taxes can improve healthcare

The elephant in the room of business & human rights

UN submission: Tax justice and the financing of children’s right to education

14 July 2025