Nick Shaxson ■ Not In My Name: remarkable, rare voices of remorse and mortification in Luxembourg

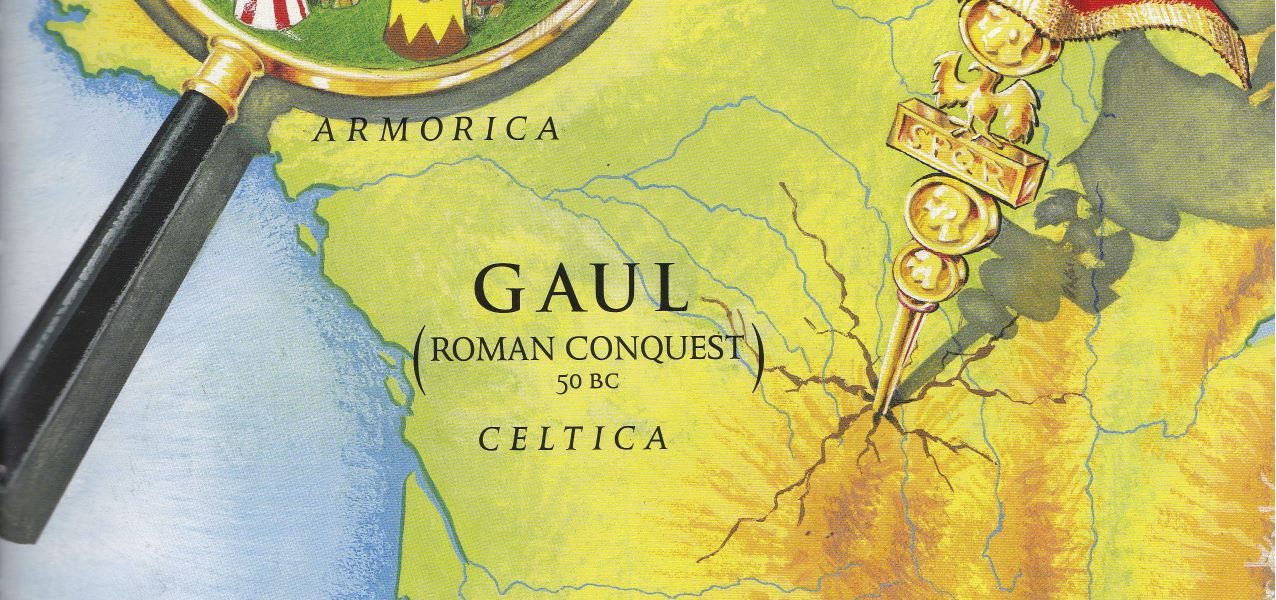

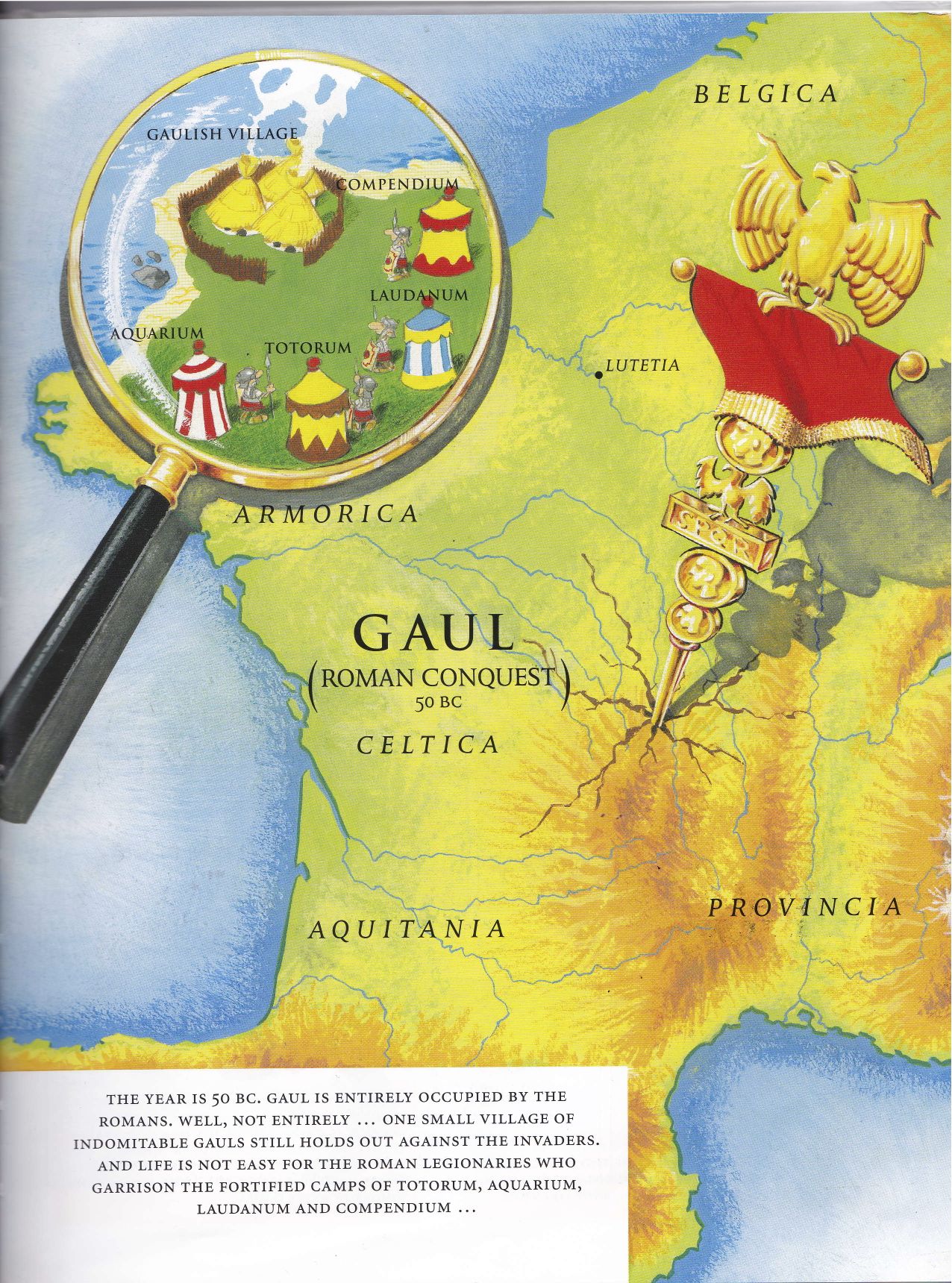

Luxembourg is entirely occupied by the offshore financial consensus. . . . well, not entirely: small bands of indominatble Luxembourgers still hold out . . .

We have often remarked on how easy it is for financial services interests to “capture” small tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions. It’s a common pattern and a woefully under-studied phenomenon where the capture by global offshore finance extends beyond the policy-making apparatus and successfully neutralises democratic dissent against the offshore finance industry.

This capture is achieved through creation of a financial consensus, the fruit of a sophisticated, loosely coordinated (or uncoordinated) long-term political, cultural and economic project (such as this one) which sees the broad spectrum of media, police and entire societies buying wholesale into a see-no-evil, we-like-the-money, screw-you-foreigners approach to tax havenry. The whole thing is sewn together by a carefully constructed theatre of probity and culture of denial that the jurisdiction in question is doing anything wrong, and that the critics ‘don’t understand’ and are out to get them.

This is usually enough to get the job done, although there are always harsher measures (such as this or this) if more is needed.

We’ve seen this capture, an important element of a broader phenomenon we call the Finance Curse, again and again, and there’s been plenty of it in Luxembourg following the large-scale “Luxemboug Leaks” revelations, which continue to reverberate.

And yet. Financial capture is never quite complete, no matter how small the jurisdiction, or how aggressive the financial industry. In 2009 we wrote about an NGO report critical of the offshore financial sector, which was rapidly squashed.

Now we are delighted to see this wonderful, thoughtful, and perhaps surprising contribution from two indomitable Luxembourgers, Luc Dockendorf & Benoît Majerus, who have stuck their necks out at some professional risk, and – speaking from our knowledge of how it’s happened in other tax havens – perhaps at risk of personal friendships and other things too. Their words do confirm plenty of what we’ve been saying all along. We reproduce it here, with permission.

For a new social contract for Luxembourg

In the words of American author Upton Sinclair, written 80 years ago: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

These past two weeks, the so-called #LuxLeaks affair has been the talk of the town: between 2002 and 2010, over 340 multinational corporations have “saved” massive amounts of tax with the help of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), benefiting from Luxembourg’s legal system and the proactive help of Luxembourg’s authorities. This was done thanks to creative accounting trickery, commonly known as “base erosion and profit shifting” (BEPS).

Our government reacted quickly, with three main arguments:

1. such tax rulings exist in very many countries (more to the point: “everybody else is doing it, so why shouldn’t we?”)

2. this practice is legal and in conformity with existing rules (“we haven’t done anything wrong”)

3. we’re not proud of what has been done, so we’ll change things (“we’re going to get serious about transparency”).

There were myriad reactions in the local press and on social networks. Most ran along the lines of “we’re not the only ones doing this” or “they’re all just jealous”. However, this simply doesn’t tackle the actual, underlying issue.

We would like to submit a simple statement: what’s been done in our name all these years isn’t right.

Even if something is legal, it can also be profoundly unjust.

If we do not understand the difference between these two concepts, we have to go back to history class or look no further than the many countries the world over in which injustice and human rights violations are happening on a daily basis behind a smokescreen of legality.

Just because others are doing something doesn’t imply that we have to do it as well.

The #LuxLeaks affair is symptomatic for a Luxembourgish model which relies on financial niches which damage other countries: another well known example is the so-called tobacco- and petrol tourism.

We feel that the argument “others are doing it as well” is fallacious: societal models must be grounded in positive choices, not in the best possible capacity to cheat.

We have all reaped the benefits of that system; we’ve been living the good life, but we’ve been living well beyond our means. Most of those who live and/or work in Luxembourg earn unrealistically high wages in order to pay for unrealistically high costs of living. We have long shied away from recognising this, but our productive economy is significantly too small compared to the financial sector and the civil service.

And worst of all: we’ve been living at the expense of others. Not just other states, but other people, like ourselves, who have been paying their taxes, while corporations in their own countries have been dodging them. It is no longer possible to pretend that the Luxembourgish model has no negative consequences for other countries.

It’s high time that we rethink our model. Economic diversification can no longer simply be understood as an ever greater diversification of the financial sector.

We have to learn to live simpler and less materialistic lives. We have to encourage and incentivise creativity, courage and integrity, wherever possible. We have to undertake far-reaching reforms in the civil service and in public finance. We have to break every taboo about the financial sector. The (financial) burden that we shall have to bear in order to change our model will have to be shared in an equal manner – the bill cannot be footed exclusively by the workforce.

BEPS is a part of a deregulated financial system – the offshore system – which makes the rich grow richer while keeping the poor trapped in poverty, be it in Mexico, Nigeria, China or Luxembourg. There is a global tendency towards ever greater inequality: Oxfam calculated that in 2014, the 85 richest people on the planet own as much as the poorest half of humanity. That’s over three and a half billion human beings.

We have to understand that the offshore system deepens inequality by creating endless possibilities to hide money “elsewhere”. This undermines the capacities of states throughout the world to collect tax revenue which is indispensable for the socio-economic development of their countries. We must in ask ourselves whether we agree to be a part of such a system, which, at the end of the day, works only for very few people – and certainly not in the interest of sustainable development. Sustainable development needs tax justice.

We need a paradigm shift, towards a responsible economy, coherent policies and an inclusive open society.

We, who live and work in Luxembourg, have to realise and accept that our country has become part of the offshore system; that our Rule of Law has been hijacked by financial interests. Only by acknowledging and naming the problem can we hope to be able to tackle it.

Luxembourg needs to rethink, retool and future-proof its societal model.

Most urgently: we can’t afford to waste any time. The so-called Luxembourgish model in its current form is no longer viable. At some point, even Luxembourg can no longer compete in the race to the bottom of fiscal dumping or tax wars. If we want to avoid to have a different societal model forced upon us, as has, for instance, been the case in Greece, we had better change it ourselves. Now.

Many of us are working towards this: in the private sector, in civil society, in the civil service. This is no declaration of war against the financial centre: we have a lot of knowledge and skills in Luxembourg, which we can and must use for good.

Beyond the recent proposals of the G20, there is a plethora of other international initiatives and partnerships. There are more informal ones, like the Open Government Partnership, or more formal ones, like the OECD, where we can share ideas and lessons with other states and societies, in order to become more transparent and competitive. We need a transparency and freedom of information act, like we need a more ambitious deontological code for all public office-holders, for politicians and civil servants alike.

Only by working together can we have the democratic legitimacy to make this into a national project for Luxembourg. We need a political consensus to break with the past and write a new chapter – a new social contract.

We owe this to our neighbours, as well as to all the people who live far away from us, but feel the impact of our financial centre.

But that’s not all; we also owe it to the generation of our parents and grandparents, who build our country. Their motto was not: “We want to retain what we have.”

And most importantly: we owe it to our children’s generation.

Luc Dockendorf & Benoît Majerus

This text was published in Luxembourgish in the Luxemburger Wort of 22 November 2014. It also exists in French, German, Portuguese and Spanish.

Benoît Majerus is a historian and teaches at the University of Luxembourg. Luc Dockendorf is a diplomat and is working at the Permanent Mission of Luxembourg to the UN in New York. He has written this text strictly in his private capacity; the opinions contained therein do not commit his employer. He is not politically affiliated.

Related articles

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The myth-buster’s guide to the “millionaire exodus” scare story

Money can’t buy health, but taxes can improve healthcare

The elephant in the room of business & human rights

UN submission: Tax justice and the financing of children’s right to education

14 July 2025

We should not forget that a much greater source of income is VAT on Internet sales and petrol, which is a very simple “business”.

I am very impressed by this enlightened article that comes after a period of time when we as a group have despaired of the Luxembourg judicial system. It clearly illustrates the reason behind the quite impossible obstacles that have been placed in our path to seek justice and a fair hearing for our cause within the borders of Luxembourg.

We have been fighting the administration of Landsbanki Lux for 6 years having been sold an equity release scheme that was, with the knowledge we have acquired over that time, blatantly fraudulent, and dishonest. A scheme devised by individuals whose main aim was to strip assets from the unsuspecting elderly pensioners that they enticed into their web of promises of a safe investment and offering security in their twilight years.

The door to sensible dialogue prior to legal proceedings has been firmly closed reminiscent of Charles De Gaulle and his famous “NON”. We have been informed that there has been absolutely no wrong doing in our many cases without the chance of any meaningful discussion. This means that Luxembourg is blatantly ignoring the basic principles of administration and that hundreds of pensioners are facing the prospect of eviction in the future.

As Dockendork & Majerus say in their article “”that the rule of law has been hijacked by financial interests” It is indeed time for change, and the sooner the better.

Nina Foster for:

http://landsbankivictims.co.uk/

https://www.facebook.com/605068499505134/photos/a.619265181418799.129660.605068499505134/639779722700678/?type=1

I should add that these actions fly in the face of actions taken by other countries in the Landsbanki affairs where action is being taken by the supreme court in Paris, and 3 directors of the bank have recently been imprisoned.