Nick Shaxson ■ Three Illicit Flows Targets for the Post-2015 Framework

From Alex Cobham at the Center for Global Development, with hat tip to Tax Research. For an earlier article about the post-2015 framework, please click here.

Three Illicit Financial Flows Targets

There is broad consensus on the need for the post-2015 successor framework to the Millennium Development Goals to respond to the challenge of illicit financial flows (IFF). Typically IFF involve the hidden movement of profits, hidden transfers of ownership, or hidden income streams. The main motivations are tax evasion (corporate and individual); laundering the proceeds of crime (largely human trafficking and drug trafficking); and corruption (including the theft of state assets and the bribery of public officials).

Current proposals reflect the need for international action to counter IFF, since the damage done by IFF in one jurisdiction is typically dependent upon the financial secrecy provided by another. But they are framed only at the most general level in terms of reducing IFF (without saying who should do this, or how), or of “international support to improve domestic capacity for tax collection” (without outlining the international obstacles that prevent domestic progress).

What is lacking, above all, is the specificity to hold policymakers accountable, globally and in individual jurisdictions, for meeting the responsibilities that these broad commitments entail. To have a chance of being effective, the targets must make explicit that which is currently implicit only. For the many jurisdictions that provide financial secrecy that damages others, from Switzerland and Delaware to Jersey and Singapore, that means specific, measurable commitments to the emerging norms of transparency. For those countries that suffer as a result, it means an empowering measure of progress in the transparency of trade and investment partners – and the opportunity to challenge those partners which fail to show progress.

In a new paper for the Copenhagen Consensus, I propose three post-2015 targets to curtail illicit financial flows. Not only do these targets offer a level of policy accountability that current proposals simply do not, they are also characterised by high benefit-cost ratios — even allowing for the inevitable uncertainty. In net present value terms, over the framework’s likely period of 2016–2030, the potential net benefits are in the very high billions or low trillions of dollars.

New targets

The three targets I propose:

- To eliminate anonymous ownership of companies, trusts, and foundations.

- To ensure all bilateral trade and investment flows occur between jurisdictions which exchange tax information on an automatic basis.

- To ensure all multinational corporations publish data about their economic activity and taxation on a country-by-country basis.

Each of these is already part of its own well-established process. The G-8 meeting of 2013 saw high-level rhetoric, and some country progress, around the need to end anonymous ownership. Sixty-four countries and jurisdictions are now committed to the OECD’s new standard for automatic information exchange, starting multilaterally from 2017. And country-by-country reporting is increasingly required for a range of industries in the European Union and US, while the OECD is drafting a reporting template for all multinationals to report to all tax authorities; the remaining issue relates only to publication of the resulting data.

Cost-benefit analysis

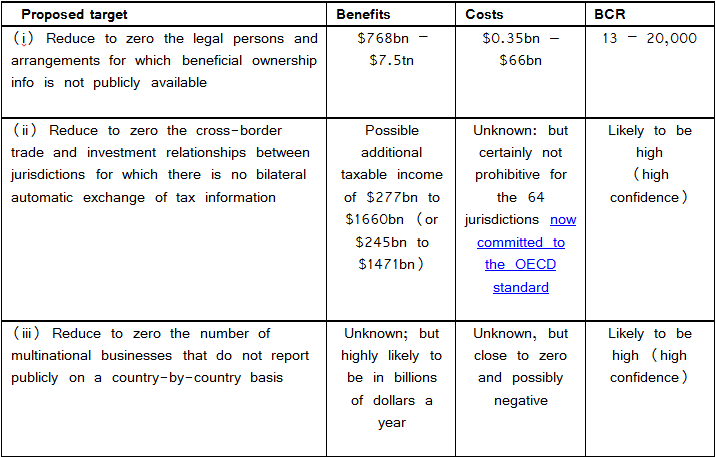

The basis for the specific proposals and their potential to contribute to reductions in illicit financial flows is detailed in the full paper. The additional contribution is to use available cost and benefit data to estimate overall benefit-cost ratios.

As the table shows, the ranges are either very wide or unknown. It should be made a priority in each of the processes discussed for better data on costs and benefits to be collected on an on-going basis. Even with the existing data, however, and making broadly conservative assumptions throughout, it is evident from the analysis that the potential benefits are likely to exceed the costs many times over.

Full details of the calculations are provided in the paper, and as part of the process the Copenhagen Consensus has also commissioned valuable, critical commentaries from Prof. Peter Reuter, from Global Financial Integrity, from UNODC, and from Policy Forum (Tanzania). [The Copenhagen Consensus is in the process of putting together equivalent work across the range of post-2015 themes; equivalent proposals and critical commentary are already available for education.]

There is scope to improve significantly the evidence base over the next two years, as initiatives in each area go forward — and those involved, not least the OECD, should ensure that the collation of performance data is prioritised so that these gains do indeed crystallise. But the evidence already points towards what are likely to be very large net benefits indeed from global measures to address illicit flows that include the specific, accountable targets detailed in the paper.

Range of benefit-cost ratios for proposed targets

See also: Bjorn Lomborg’s op-ed in Graphic Online (Ghana) and a piece from the WSJ’s Matina Stevis

Related articles

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The myth-buster’s guide to the “millionaire exodus” scare story