Nick Shaxson ■ Foreign investment – smaller than you might believe

From Jesse Griffiths, Eurodad, with permission.

From Jesse Griffiths, Eurodad, with permission.

Foreign investment – much smaller than you might believe

You may have seen that foreign direct investment (FDI) was judged last month to have finally regained pre-crisis levels, and that a record percentage of all FDI – 52% – went to developing countries in 2013. The UN’s figures say $759 billion of new investment flowed into developing countries in 2013, right? Well, no actually they say nothing of the sort, but it requires a bit of digging to understand why. Below are four important caveats that everyone talking about FDI should bear in mind, which emerge when you read UNCTAD’s full analysis from its World Investment Reports (the one for 2013 comes out in June).

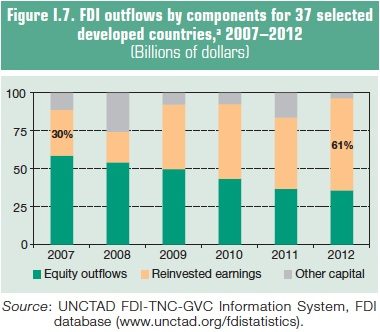

1. Much FDI is not new inflows, but the reinvestment of profits made in the recipient country. In 2012, reinvested earnings accounted for over 60% of ‘outward’ FDI from developed countries [see Fig. 1.7 here, added by TJN]. A strong case can therefore be made that this could be regarded as domestic investment.

2. Huge profits are extracted by the foreign investors. In 2011, profits flowing out of developing countries were equivalent to almost 90% of the investment flowing in.

3. Widespread rerouting of FDI through tax havens to facilitate tax avoidance and evasion mean the figures are overstated and extremely unreliable. For example, the British Virgin Islands – thirty thousand souls mostly living on a 20km strip of land in the Caribbean – was, in 2012, the fifth largest recipient of FDI and the tenth largest investor in the world. [See Fig 1.2, added by TJN. We’d add that round-tripping is a massive fly in this ointment] This absurdity is caused by investors routing their money through the islands – a British overseas territory – probably to dodge taxes. (In fact the figures would be even more absurd had UNCTAD not already tried to remove some distortions – by excluding FDI routed through special purpose entities in the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Hungary from its data.)

3. Widespread rerouting of FDI through tax havens to facilitate tax avoidance and evasion mean the figures are overstated and extremely unreliable. For example, the British Virgin Islands – thirty thousand souls mostly living on a 20km strip of land in the Caribbean – was, in 2012, the fifth largest recipient of FDI and the tenth largest investor in the world. [See Fig 1.2, added by TJN. We’d add that round-tripping is a massive fly in this ointment] This absurdity is caused by investors routing their money through the islands – a British overseas territory – probably to dodge taxes. (In fact the figures would be even more absurd had UNCTAD not already tried to remove some distortions – by excluding FDI routed through special purpose entities in the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Hungary from its data.)

4. FDI is heavily concentrated in a few countries – very little goes to the poorest countries, except to extract natural resources. In 2011, 70% of FDI to developing countries went to just 10 countries.

In 2012 there were 3,196 investment treaties globally, many of them affecting developing countries. There are also important investment chapters in free trade agreements. Companies are increasingly using these treaties to sue developing country governments. 2012 saw the highest number of international claims filed against states by foreign companies, with 66% filed against developing countries. All of this suggests we should care much more about the quality of foreign investment, rather than the quantity. Unfortunately, investment and trade treaties often undermine developing countries’ efforts to insist on quality investment that creates employment, respects standards, and doesn’t contribute to economic crises.

As the South Centre has noted, the treaties often discriminate against developing country governments through vague definitions of key terms such as ‘investment’ and ‘fair and equitable treatment’ that can make it impossible to make investors comply with domestic laws. In practice, these treaties and agreements can make it harder for developing countries to maximise the benefits of the FDI, for example by restricting their ability to require technology transfer or employment of local staff. They may also restrict the ability of governments to prevent ‘hot money’ outflows from destabilising their economies. Environmental and social standards? Not if they ‘discriminate’ against foreign companies. So rather than getting excited about the scale of FDI– it’s far smaller than the headline figures suggest – we should turn our attention, as ever, to the rules and policies that prevent developing countries from getting the best from it.

Related articles

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025