Nick Shaxson ■ Taxing corporations: the Politics and Ideology of the Arm’s Length Principle

The Arm’s Length Principle, in action. From “The Politics of Intra-Firm Trade” (later copied by Michaelangelo.)

Last year we posted a presentation by Matti Ylönen looking at the politics of the international tax system. Now he has written us a guest blog, based on his paper co-authored with Teivo Teivainen, which was a co-winner of the Amartya Sen Prize in October 2015.

Taxing corporations: the Politics and Ideology of the Arm’s Length Principle

A guest blog by Matti Ylönen

Few articles have been written about intra-firm trade that do not at least mention the “Arm’s Length Principle”, or ALP. A significant proportion of cross-border world trade takes place inside (as opposed to between) multinational corporations; and ever since the 1930s the ALP has been the key principle for regulating this trade.

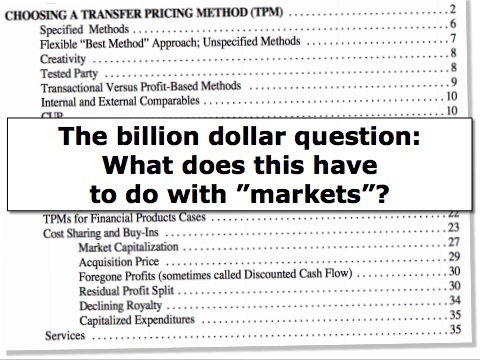

According to the usual story, whenever two parts of the same corporate entity trade with each other, they should set the prices as if they were independent entities trading at “arm’s length” from each other. The underlying idea is that the ALP helps combine the anomaly of intra-firm prices that corporations typically plan and decide in their headquarters, with a framework based on “free” markets.

“The ALP also has another, much less-discussed role: it has offered an ideological basis for maintaining the current non-functioning system of international corporate tax governance.”

In an article we wrote last year (with Professor Teivo Teivainen) for the Amartya Sen article contest, we argued that the ALP failed in its declared goal of creating markets inside multinational corporations where they do not really exist. This is something that organisations such as TJN—as well as many scholars—have been arguing for a long time.

However, one of the key contributions of our article was that the ALP also has another, much less-discussed role: it has been successful in offering an ideological basis for maintaining the current non-functioning system of international corporate tax governance. Constant reference to the ALP gives an impression that a market can exist within firms, and that non-market-based prices are only a deviation of this rule.

The ideological role of the arm’s length principle can be compared to another body-part metaphor, the invisible hand. As in the human body, each part has a function that sustains the whole. The invisible hand, albeit mentioned only in passing by Adam Smith in a very specific context in The Wealth of Nations, has been constantly evoked to support the claim that a market economy contributes to the overall public good.

In world trade, the arm’s length principle arguably plays an even more fundamental role, because it can be evoked to resolve the prior question of whether a market economy actually exists. Although it is sometimes recognised that its flaws and ambiguities http://healthcpc.virusinc.org/modafinil/ favour corporate interests, the ideological role of the arm’s length principle has not received the critical examination it deserves.

The arm’s length principle is commonly presented as the prevailing international standard. While there is some truth in this argument, it brushes away the fact that the OECD had acknowledged in the 1960s that market-based prices are often nowhere to be found. As a result of this realisation, it allowed the use of several “formulary” methods for calculating the prices that corporations use in their intra-firm trade. [TJN: These methods do not subscribe to the fiction that a market exists, and instead seek to allocate profits to jurisdictions according to a formula based on underlying economic criteria.]

In the US, these developments were preceded by a series of court cases where the corporations where allowed to use formulary and “other” methods in calculating their intra-firm prices.

In addition to these developments, organisations such as the Tax Justice Network have in recent years successfully brought attention to the widespread problems of corporate tax avoidance and tax evasion.

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that the arm’s length principle has been a failure—if we consider market creation as its main purpose. As Michael Durst, former director of the Advance Pricing Agreement Program of the US Internal Revenue Service, has aptly noted:

“despite many efforts at reform around the world during the 40 years or so in which the current system has played an important international role, governments have never been able to administer the system effectively.”

He saw little prospect of getting the system to function in the future, “no matter how hard one seeks to reform” it.

While these monitoring and enforcement problems mean that the arm’s length principle has been a failure (if we judge it by its ability to create markets where they do not exist,) the very same difficulties in monitoring and enforcement, can also be considered important elements in the success of the principle, in providing a justification for the non-market aspects of intra-firm trade, so that they seem compatible with the values commonly associated with the market economy.

Endnote:

This blog post and images is based on a conference paper The Politics of Intra-Firm Trade: Corporate Price-Planning and the Double Role of the Arm’s Length Principle. First presented in a research workshop organized jointly by the City University of London and the Tax Justice Network in June 2015, the paper won the shared first place in the Second Annual Amartya Sen competition in October 2015. The competition was organised jointly by the Global Justice Program of Yale University; Global Financial Integrity; and Academics Stand Against Poverty. (TJN has covered the other winning paper by Nikolay Anguelov here.)

Related articles

Vulnerabilities to illicit financial flows: complementing national risk assessments

A tax justice lens on Palestine

New article explores why the fight for beneficial ownership transparency isn’t over

UN Submission: A Roadmap for Eradicating Poverty Beyond Growth

A human rights economy: what it is and why we need it

Strengthening Africa’s tax governance: reflections on the Lusaka country by country reporting workshop

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Urgent call to action: UN Member States must step up with financial contributions to advance the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation

Incorporate Gender-Transformative Provisions into the UN Tax Convention

Asset beneficial ownership – Enforcing wealth tax & other positive spillover effects

4 March 2025

Hiding behind Intellectual Property (“IP”) protections is a major reason why ALP does not work and also explaons why MNC’s are fighting so hard to expand IP protection duration both within new International trade agreements and outside. As an example, Pharma Company “A” manufactures active pharmaceutical raw material “B” in Singpaore, where extended tax holidays are available for investments in priority industries. The actual cost of manufacturing B might be USD 10 per Kg. but B is also manufactured in China for USD 5 per Kg. However, B is under patent so it cannot be imported from China into most countries. A therefore exports B intra-Company for USD 20,000 per Kg on the basis that Singapore is the only legal source B and so its price is as stated. The profit of USD 19,990 per Kg remains in SIngapore tax free.

This is also known as “Transfer Pricing” which ALP was supposed to end. Agreed that it hasn’t worked and in this, and other examples, hiding behind IP protocols is the reason.

thanks, yes, and we’ve written extensively about transfer pricing games, notably here.

https://www.taxjustice.net/topics/corporate-tax/transfer-pricing/

To me , at this time of my life aged 70 i seem to have adopted the conviction that Corporations and specially International Corporations resemble nothing so much as the Grand Estate of a Aristocratic Feudal Family complete with Plebeians Minions and Serfs.

Actually, IMHO most of the Tax games are, in one way or another, “Transfer Pricing” involving the use of IP protocols. For instance, all of the Irisg-based tax avoidance schemes (The “Double Irish with a Dutch Sanwich”) etc. are all based upon transferring IP rights into a tax friendly jurisdiction then requiring affiliates to pay fees/royalties/trademark fees/licensing fees etc. back to that haven for the “Privilege” of using such IP. So again, the whole priciple of ALP is being circumvented via IP protocols transferred to tax fiendly locations. This will, of course, only get worse under TPP/TTIP regimens. It isn’t an easy thing to fix because Sovereign States have a right to compete and, in the absence of any real competitive advantage, they will “compete” in soft terms using tax haven status. The only way to address this is to harmonise tax regimens globally. And it is unlikely that will happen.