John Christensen ■ The Finance Curse and Competitiveness: presentation at Max Planck Institute

This is the text of a lecture that John Christensen, Director of the Tax Justice Network (TJN), gave at the Max Planck Institute in Cologne this week.

National Competitiveness: A Dangerous Obsession

By John Christensen

Thanks to the exquisite timing of the Guardian newspaper, today’s edition carries a long read article about the very issue I plan to address this afternoon. The British Channel Island of Jersey – where I grew up – was an early adopter of a development model based on the state working with international financial Capital to create a “competitive” regulatory and tax environment.

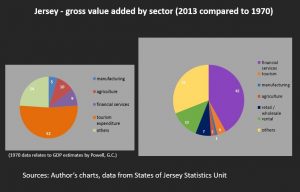

In the 1970s Jersey rapidly transformed itself into an offshore tax haven satellite of the City of London. Within a decade the tax haven activity had crowded out the island’s pre-existing industries (tourism, light manufacturing and horticulture). By the 1990s the island was perilously over-dependent on its offshore financial centre role, and the state had become captive to the dictates of the finance nexus: Jersey had succumbed to the phenomenon of the Finance Curse.

As the Guardian points out, however, what applies to Jersey arguably applies also to Britain — which poses a far greater threat to global economic and social stability. Britain’s commitment to a “competitive” development strategy, sounds ominously similar to what has brought the island of Jersey to its downfall.

There is an urgent need to shift the academic discussion of state “competitiveness” into the wider arena of public debate. TJN has a role to play in this process, and our recent publications on tax competitiveness (slide one) and the Finance Curse (slide two) are the core of my talk today.

Tax competition

Tax competition is back in the frame:

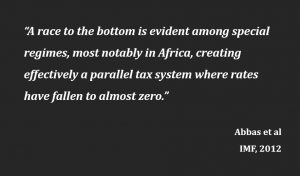

• Evidence is mounting that lobbying pressure to grant tax holidays, accelerated depreciation rates, preferential treatments, export processing zones, and other incentives to investors in Africa is driving

effective tax rates down to near zero, with subsidies in some sectors taking the effective rate into negative territory (slide three);

• In Europe the advanced tax agreements negotiated by PWC with the Luxembourg government are under challenge on the basis that they constitute illegal state aid which harms competition within the single market (slide four);

• Inter-state tax competition has increased steadily in the United States, with a huge variety of economic subsidies being available at state, county and city level. Specialised ‘location’ consultants act on behalf of businesses to pressure state and city authorities to maximise subsidies and tax breaks for their clients (slide five);

• Republican candidates for the US presidential elections in 2016 are calling for complete abolition of the Corporate Income Tax (CIT) on the grounds that the U.S. needs to ‘compete’, and most are committed to abolishing FATCA, a cross-border information-sharing mechanism;

• In the United Kingdom, prime minister David Cameron is committed to Britain leading the global race to the bottom on tax, and to pushing for radical reform of the EU to increase state ‘competitiveness’ (slide six).

The Tax Justice Network and transparency

Since launching TJN in 2003 we have largely concentrated our research and advocacy effort on strengthening international transparency measures. The rationale behind this focus was based on our view that improved information exchange can significantly strengthen national attempts to tackle tax evasion by owners of offshore portfolio capital, while a new accounting standard for country by country reporting by multinational companies will help tax authorities identify when profit-shifting is occurring.

In 2004 we put out a call for a new global accounting standard for multinational companies which we called country by country reporting. Initially our proposal was rejected as impractical and expensive. More recently MNCs have tried to block CBCR on the basis that the tax information it disclosed is commercially confidential. CBCR is now being developed as a global standard by the OECD, and last week the French National Assembly rejected strong MNC lobbying and voted in favour of public reporting.

In 2005 we called for rejection of the OECD’s impractical standard for information exchange between countries on a by request model and proposed instead a multilateral standard for automatic information exchange. For 7 years our demand was blocked by governments of tax havens, but in 2012, with

support from the Indian government, AIE was agreed as the new global standard by the G20. The OECD is currently developing a Common Reporting Standard for automatic information exchange.

In 2005 we also called for new public registries of the beneficial ownership of companies as a means of tracking corrupt transactions hidden behind secretive offshore shell companies. In 2013 G20 committed to taking action on this front as well.

Clearly significant progress is being made – albeit slowly and in the face of strong resistance – towards a degree of greater transparency of the global financial markets. However, this does not mean that we are necessarily rolling back the problem of taxing and regulating Capital in an era of near perfect capital mobility.

The problem of taxing capital

For several years, and particularly since our campaign of naming and shaming prominent tax avoiders forced governments to at the very least appear to be taking action, MNCs and wealthy people have been fighting back against efforts to tackle tax evasion and avoidance.

With public opinion in most countries strongly against tax dodging, they have opted to use their immense lobbying strength to

(i) Resist pressure for stronger international cooperation on tax information exchange

(ii) Deepen political commitment to tax competition

In practice it seems increasingly clear that the ultimate goal is the complete abolition of the corporate income tax (which, by the way, several Republican candidates for the US presidency have signed up to).

Their political strategy is to target key political allies in countries like Britain and the USA, and to degrade the CIT to the point where it becomes politically viable to call for its abandonment. In response we have issued a report on why keeping the CIT is crucial to maintaining a balanced and equitable tax regime.

But the political rhetoric in favour of tax and regulatory competition has increased significantly in the past three years, and that is the subject I aim to address today.

Tax competition has been on TJN’s agenda since our launch in 2003, and some of our regional chapters have given this priority over global transparency initiatives. TJN Africa, for example, has been addressing regional tax competition in eastern Africa, and more recently western Africa, challenging governments over the incentives they offer to MNCs wanting access to their markets or their resources. In almost all cases these tax incentives serve no useful purpose whatsoever (slide seven).

At country level our colleagues in Kenya have challenged that country’s government over its double tax treaty arrangements with the tax haven of Mauritius, which make far too many concessions on the taxing of investment routed via Mauritius.

Britain: leading the race to the bottom

I want to focus on Britain, where successive governments have put tax competition at the heart of economic development strategy. Both the government and its opposition have stated their intention of making Britain the most tax competitive nation in the OECD. Prime Minister David Cameron has used the hashtag #global race to signal the importance he attaches to the Competitiveness Agenda, and when he talks about boosting Europe’s ‘competitiveness’ he is actually offering a radically different model to the cooperative ideal of the EU’s founders. A clear choice is now being proffered between the welfare state on the one hand and the competitive state on the other. Cameron’s strategy is to use race to the bottom tactics to undermine the former and reinforce the latter.

In the past decade the nominal UK corporate income tax rate has been reduced from 30 percent to 18 percent. But for many MNCs the effective tax rate is in single figures, partly due to relaxation of Controlled Foreign Corporation rules and the introduction of a patent box provision, which encourages MNCs to locate royalty payments in the UK. What is extraordinary about this provision is that HM Treasury has conceded that the patent box tax break will allow MNCs to reduce their tax payments by many billions annually without ever paying for itself at any time in the foreseeable future.

Why would any responsible government want to adopt such a tax policy? I fear the answer lies not in the realms of economics – this is clearly not efficient in any meaningful sense of that term [and there is no evidence that the patent box will actually incentivise any research into innovation.] Rather, this extraordinary political concession to Capital has been made because the political processes in Britain have succumbed to the political economic phenomenon known as the Finance Curse (which I will discuss later on) – slide eight.

Fiscal policy in Britain, especially relating to corporate tax and corporate subsidies, is now largely controlled by MNC lobbies, with major accounting firms acting as close advisers to both government and opposition. To exemplify the extent to which control has been passed to Capital, in 2010 the incoming coalition government appointed a committee almost entirely consisting of MNC representatives to review UK tax policies relating to corporate taxation. Unsurprisingly the MNCs – like a bunch of children let loose in a cake shop – grabbed whatever they could take, including relaxed CFC rules, patent boxes, and lower tax rates.

Has this resulted in increased investment or innovation or productivity? None of those objectives have been achieved.

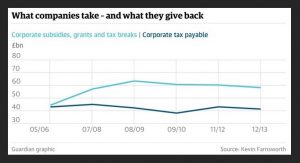

Britain finds itself in the perverse situation of apparently receiving significantly less revenue from the CIT than it pays out in direct and indirect subsidies to the corporate sector (slide nine). These estimates from Kevin Farnsworth at Sheffield University are contested, however the UK government has not produced data of its own, and this chart suggests the general direction of travel of capitalism in the current era; the ability to free ride, and to extract state subsidy is taking us in the direction of the corporate welfare state.

Prime Minister Cameron’s #globalrace hashtag doesn’t simply relate to a race to the bottom on corporate tax rates. His ‘competitiveness agenda’ also touches on energy policy, environmental policy, welfare, labour protection and financial regulation. Despite the financial crisis, which had strong roots in the famously ‘light touch’ regulation of the City of London, the UK government is strongly resistant to measures aimed at strengthening regulation of the City of London and crucially, of its tax haven satellites.

And it’s the City’s tax haven satellites that I want to turn my attention to now, because these have been my focus of research for over three decades, and in many respects these places serve as indicators of how financial capitalism – especially banks, hedge funds, private equity funds, and accounting firms – have shaped, and are still shaping, a Competitiveness Agenda to suit their purposes.

As you’ve already heard, for 11 years I was economic adviser to the government of Jersey, a British tax haven with close political and economic links to the City of London (the island likes to describe itself as “an extension of the City of London”).

Jersey was an early adopter of the Competitiveness Agenda. In the mid-1970s, when the island’s offshore financial sector started to take off, it adopted highly permissive company and trust laws. Banks from around the world were licensed to operate in a virtually non-existent regulatory framework, and the vast majority of companies registered in the island were exempted from paying any tax whatsoever.

Competitive advantage and comparative advantage: two different beasts

In 1981, when I first interviewed the government’s then Economic Adviser, he told me that tax and regulatory competitiveness was central to the island’s development strategy. The island’s Bailiff (the president of the parliamentary assembly) subsequently said that Jersey has a comparative advantage in legislation and taxation of trusts and companies.

I have heard similar claims about comparative advantage made by politicians and bankers in Ireland, Cayman and Delaware. Having studied Ricardo and subsequent theorists’ work [also see here] on comparative advantage, I’m at a complete loss as to what this means, other than that these tiny jurisdictions are able to use their sovereignty as a tool for providing mechanisms that enable Capital to escape its legal, fiscal and moral obligations elsewhere.

Jersey: the ‘flexible’ captured state

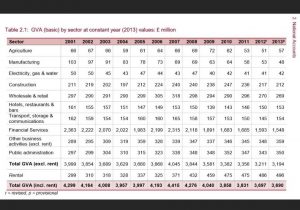

Jersey’s development goal was not to attract FDI into its pre-existing industries. As these charts show, the tourism, light manufacturing and horticultural sectors that thrived in the 1970s have almost entirely disappeared as investment switched to offshore portfolio flows and MNC profit-shifting (slide ten).

What Jersey offered was deep secrecy to the owners of portfolio capital from other countries, combined with a highly permissive tax and regulatory environment for the banks, shadow banks, hedge funds and other users which could book profits generated in other countries, and avoid regulatory scrutiny.

Jersey’s Competitiveness Agenda, in other words, lay with acting as a platform from which the City of London can promote its programme to deregulate or sidestep financial regulation elsewhere and catalyse race to the bottom dynamics around the world.

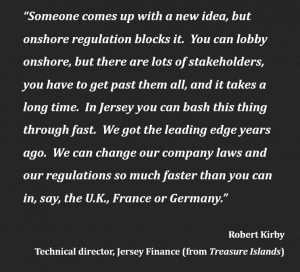

As you can see from this quote from an interview with Robert Kirkby of Jersey Finance (an industry lobby which works closely with the government) Jersey takes pride in its nimbleness when it comes to financial regulation (slide eleven). Pre- financial crisis few people paid attention to how these offshore satellites were being used by international banks to shape a permissive regulatory environment for their offshore operations in places like Jersey or Ireland. Nor have many people understood how the permissive measures adopted in Jersey might be transferred to the mainstream capital markets by using leverage on governments like the UK government to degrade its own tax and regulatory regime in a race to the bottom led by tax havens like Jersey operating at the margin of public scrutiny (importantly, there are no universities or think tanks on Jersey and the island’s only newspaper is entirely uncritical in its coverage of offshore finance).

Banks and shadow banks weren’t the only agencies propelling this race to the bottom push for tax breaks and deregulation. In the 1990s, while serving as a economic adviser to Jersey, two global accounting firms – E&Y and PWC – approached senior island politicians with a proposal to introduce a Limited Liability Partnership Law. At that time both global partnerships were facing potentially ruinous law suits over failed audits in the USA and Europe. They were urgently seeking to restructure themselves to enjoy limited liability protection of their partners, which still enjoying the tax breaks given to partnerships. The US government and the UK government were resistant to their lobbying.

By the time they approached politicians in Jersey they had already drafted a model law that was highly permissive on matters such as disclosure, and what they needed was a pliant jurisdiction that would be an early adopted and could be used to force other governments to play copycat.

Once the government of Jersey adopted their permissive version of a Limited Liability Law, they used the threat to relocate headquarter operations from London to Saint Helier as political leverage on the UK government to introduce similarly permissive legislation. This is exactly what happened. Partners from E&Y and PWC subsequently boasted about their success in forcing through legislation which had no relevance to Jersey but forced the UK government to participate in a regulatory race to the bottom (slide twelve). [for more on this episode, see Chapter Six here, or the “Ratchet” chapter in Treasure Islands, embedding it in a wider political-economy framework.]

Now the reason why E&Y and PWC could successfully use Jersey as a legislative battering ram to force regulatory and tax competition on other states is because Jersey is a case study of a phenomenon known as the Finance Curse.

From Resource Curse to Finance Curse

Most if not all of you are familiar with the notion of the Resource Curse (slide thirteen).

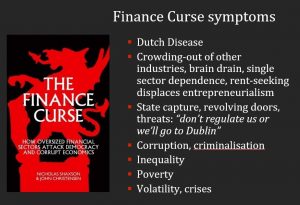

The Finance Curse has similar attributes (perhaps not surprisingly given the immense political power that both banks and fossil fuel producers enjoy), but differs in some important respects: notably that while the harmful potential of the Resource Curse is largely domestic in its impact, this is not the case for the Finance Curse (slide fourteen).

The ability of mobile international capital to capture the legislatures of small island states like Jersey, Bahamas, Cayman and so on, provides it with powerful political levers to exert pressure on Whitehall in London to similarly degrade

regulation and tax in the City. The Finance Curse has played a significant part in driving the ‘competitiveness agenda’ of international Capital.

In practice the island’s ‘competitiveness’ based strategy has not served the island well. Other small state tax havens like Cayman and Luxembourg have been able to outcompete in the US and EU markets respectively, while Mauritius, Dubai and Singapore have captured significant shares of growing demand for offshore financial services in Africa and Asia.

Jersey’s economy has become to all intents and purposes dependent on a single geographically mobile sector. In response to pressure from the EU’s Code of Conduct Group on Business Taxation, the island cut its corporation tax rate from 20 percent to zero, mistakenly believing this would attract more banks and hedge

fund activity (slide fifteen) but the government now faces its first budget deficit in over 70 years. Overall the economy is sluggish, with the only significant growth over the past ten years occurring in the rental sector of the economy (slide sixteen).

Faced with path dependency issues and no alternative skills base to draw upon, the island now finds itself incapable of diversifying its industrial base. The Competitiveness Agenda combined with extreme Finance Curse symptoms has left the island in a cul de sac.

Similar Finance Curse symptoms apply to the UK. The City of London’s sectoral interests have driven a tax cutting and deregulating agenda that has had little if any benefit to the rest of the UK economy. The City argues that without the tax

cuts and deregulation it will be unable to ‘compete’ with Hong Kong and Dubai (both emerging as regional and global offshore financial supercentres).

British politicians argue they face a prisoner’s dilemma which forces them to join the race to the bottom; we argue that this is based on a fundamental mis-understanding of competition dynamics.

First, the City of London charges about the highest fee rates in the world. If there is a concern about a lack of competitiveness the obvious solution lies with lowering the price of their services, which after all is the normal response to microeconomic competition at the level of the firm.

Second, using tax and regulatory competition to effectively subsidise financial capital is to transfer wealth from one set of actors (Labour and consumers) to Capital. There is no sign that this benefits the UK economy as a whole, and our Finance Curse analysis suggests the opposite.

Arguably, far from facing a genuine prisoner’s dilemma most politicians are captive to the ideological belief that the drive for ‘competitiveness’ forces governments to cut taxes on mobile Capital which might otherwise migrate, therefore tax cutting is virtuous since it attracts or retains investment which stimulates growth.

This argument leads politicians to the conclusion that tax competition between countries is beneficial. But just a few seconds thought reveals the circularity of the logic, which is based on a false assumption. In reality genuine productive investment (as

opposed to portfolio inflows) seeks out factors such as resource availability, infrastructure provision, labour productivity, which genuinely support productive processes. Tax breaks come way down the investment criteria, as this quote from former US Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill confirms (slide seventeen).

For the Tax Justice Network tax competition pressures pose particular threats to investment, job creation, innovation and social sustainability. Race to the bottom dynamics distort investment flows by encouraging CEOs to engage in bidding wars between states to see which will offer the highest rate of effective subsidy. Far from investment flowing to wherever it is most productive in the true economic sense, it flows to wherever MNCs can achieve the highest rate of

post-tax and subsidy profitability. In the process taxes are shifted onto Labour, reducing job creation and increasing inequality. This essentially rent-seeking behaviour of Capital is a clear negation of David Ricardo’s argument for cross border trade.

Tax ‘competition’ harms real competition

Furthermore, because tax competition is biased in favour of MNCs, preferential measures targeting FDI enable them to undercut their rival SMEs on a factor – tax – which harms innovation, job creation and consumer choice.

And so, coming to a wrapup, it is becoming clear from the limited research of recent years that the gross FDI benefits to developing countries from cutting taxes are limited while the revenue costs are substantial. In many instances attempts to measure the effectiveness of tax cuts in attracting FDI have failed to distinguish between genuine FDI flows and round-tripped capital. Tax incentives

targeting FDI have had the perverse effect of encouraging domestic capital to go offshore and return dressed up as FDI to secure preferential tax treatment and opportunities for tax avoidance.

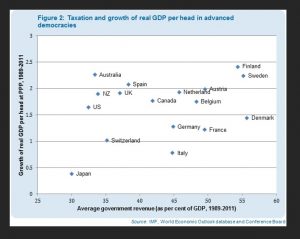

For developed economies the available research literature provides claims, counter-claims and deliberate obfuscation on the effectiveness of tax cuts in attracting FDI. Judging from the data we’ve extracted, it seems likely that tax levels have a somewhat neutral effect on economic growth, which is consistent with the view that taxes represent a transfer within an economy rather than a deadweight cost (slide eighteen).

This year TJN launched its new Fools’ Gold initiative (slide nineteen) in conjunction with Warwick University, to build a multi-disciplinary intellectual critique of ‘competitiveness’ and provide an alternative to the prisoner’s dilemma

narrative that encourages politicians to push for tax cuts and deregulation while those on the Left surrender progressive tax policies to the supposedly ‘overwhelming’ forces of globalisation.

What we hope is that a large coalition of researchers and activists can be built around a programme of policies that will bring all stakeholders of capitalism back under the control of democratic decision making (slide twenty). Without a framework for tackling tax and regulatory competition at national and international levels, it is inconceivable that we will able to bring Capital back into the Social Contract and renew the relative bargaining powers of Labour and Capital on a more equitable basis.

Thank you for listening. I look forward to your questions and comments.

Related articles

The Tax Justice Network’s most read pieces of 2024

Stolen Futures: Our new report on tax justice and the Right to Education

Stolen futures: the impacts of tax injustice on the Right to Education

31 October 2024

CERD submission: Racialised impacts of UK’s ‘second empire’

UN submission sets out racist impacts of UK’s ‘second empire’

Infographic: The extreme wealth of the superrich is making our economies insecure

Wiki: How to tax the superrich (with pictures)

Taxing extreme wealth: what countries around the world could gain from progressive wealth taxes

19 August 2024

A Call for Climate and Social Justice: Why Europe Needs a Wealth Tax