Nick Shaxson ■ Tax Justice Research Bulletin 1(5)

May 2015. Welcome to the fifth Tax Justice Research Bulletin, a monthly series dedicated to tracking the latest developments in policy-relevant research on national and international taxation.

This issue looks at a fascinating thesis on the different people and organisations that influence the OECD revision of corporate tax rules; and a new analysis from the IMF on the scale of corporate profit-shifting, with particular attention to developing countries’ revenue losses. The Spotlight falls on the Financial Secrecy Index, which has just been published in Economic Geography.

This month’s backing track, suggested by Nick Shaxson, goes out to free-riders everywhere: ‘No Charge’. (Have tissues handy while listening.)

Octopuses and arrows: Who makes and influences the international tax rules?

Last month, TJRB 1(4) looked at the OECD’s review of research on base erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) by multinational enterprises (MNEs). BEPS is the OECD’s fancy way of saying ‘corporate tax dodging.’ That review revealed a dearth of findings in a number of areas, as well as broad consensus on the importance of the problem. Untouched in that review, and little researched in generally, is the process by which policy on BEPS is made.

The historical record, back to the League of Nations and beyond, has been laid out by Prof. Sol Picciotto. (Cambridge University Press has kindly allowed TJN to republish his book International Business Taxation, first published in 1992: it’s available in pdf form, here.) Sol, one of our senior advisers, now leads the BEPS Monitoring Group, the hub for technical submissions to BEPS from civil society. And the BEPS process itself has now been subject to a detailed process analysis, in a seriously impressive Copenhagen Business School Master’s thesis by Rasmus Corlin Christensen.

The main focus is on what is known as “BEPS 13,” a point that deals with transfer pricing documentation including country-by-country reporting (CBCR). His findings reflect many interviews as well as analysis of submissions and consultations. The summary of literature, and details of the methods, are well worth the time.

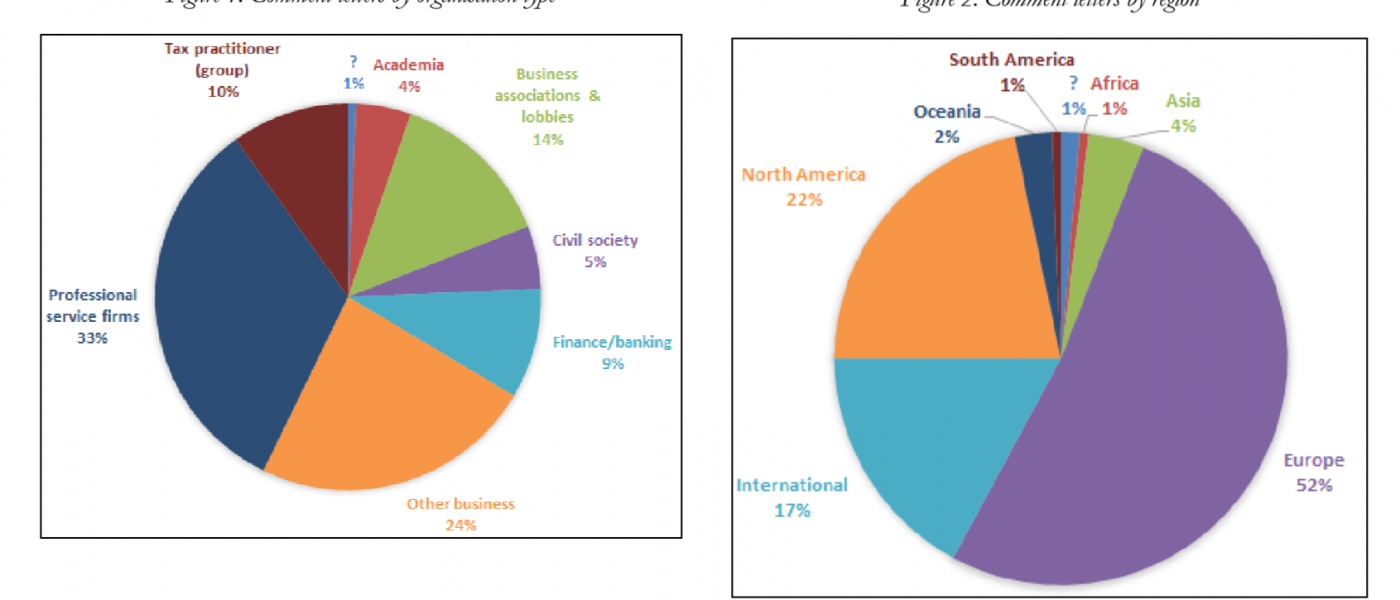

Figures 1 and 2 (click to enlarge) show the simple range of submissions to BEPS 13, in terms of organisation type and geographical origin. There’s little surprise to find that less than a tenth of the submissions came from academia and civil society; and even fewer submissions came from South America, Africa and Asia combined.

Figures 1 and 2 (click to enlarge) show the simple range of submissions to BEPS 13, in terms of organisation type and geographical origin. There’s little surprise to find that less than a tenth of the submissions came from academia and civil society; and even fewer submissions came from South America, Africa and Asia combined.

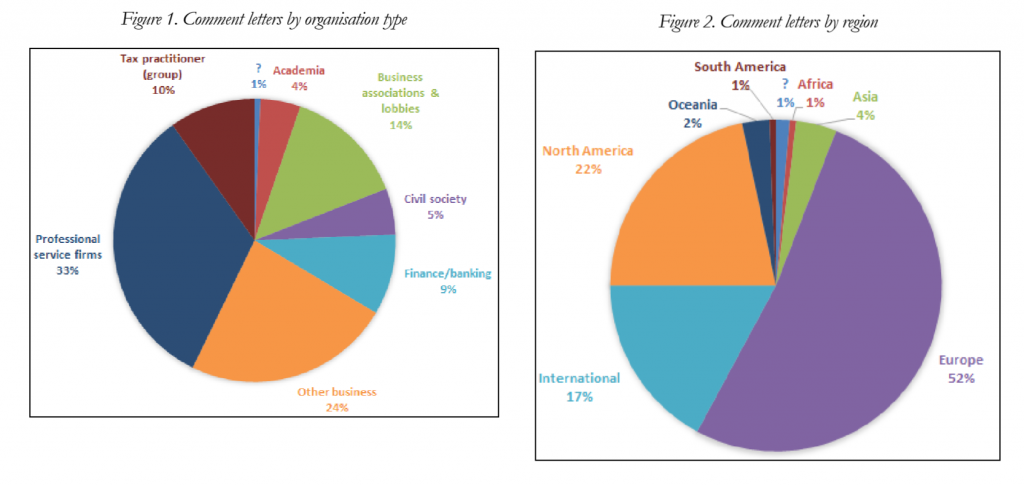

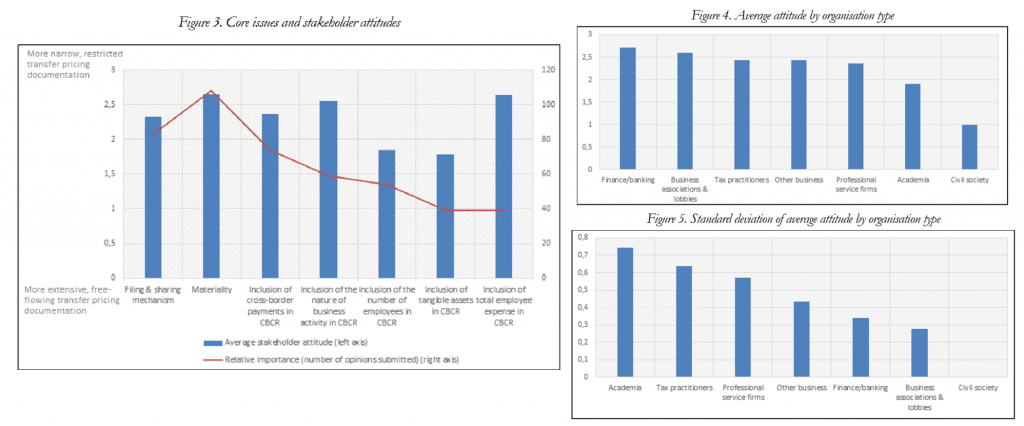

Similarly, figures 3 and 4 confirm (surprise, surprise) that business groups and professional services firms seemed to prefer much more restricted transfer pricing documentation than did academia or civil society. Figure 5 shows tax practitioners with the greatest intra-group variation of views expressed, compared to other private sector groupings, with business lobbies the least; while academia provided the most varied range of views, and civil society the least. The latter point is perhaps unsurprising given the technical nature of the process (hence relatively limited engagement); and that BEPS 13 addresses an area in which civil society consensus has emerged over a decade or so. (Indeed, the content of BEPS 13 is in good part a product of successful influence by civil society in non-specialist, political processes, not least in the UK – but that would be a whole other study.)

The analysis gets more detailed still, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where

The analysis gets more detailed still, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where

“influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.”

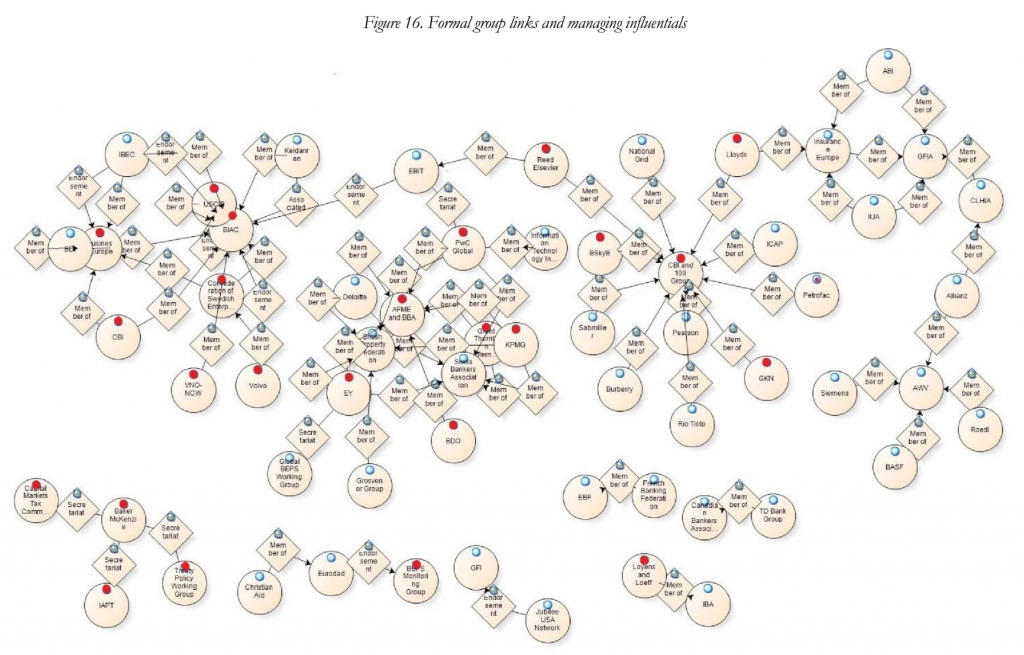

In Figure 16, the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process.

The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

[A]nalysis of the BEPS Action 13 consultation shows that it was dominated by Western tax advisers and business representatives, that there was a general preference for a limited [transfer pricing documentation] package, and that there was significant variation in attitudes between similar participating organisations. Furthermore, the discussions were highly complex, requiring substantial technical expertise, and thus limiting the range of participating organisations…

Finally, the significance of access to the right expertise and networks is visible in another articulation of professional competition in BEPS Action 13: lobby centres. Lobby centres are specific interest groups where different professionals and organisations collectively engage the policy process, spearheaded by one particular professional, who most often is influential. Peripheral professionals and groups without access will use this lobbying strategy to leverage the expertise and networks of influential professionals. This strategy highlights the importance of being able to access the right professional expertise and networks in order to make engage successfully in policy debates. However, this importance is not sufficiently recognised by the interest group literature, which emphasises organisational finances or issue attributes.

The Financial Secrecy Index: grappling with definitions of the term ‘tax haven’

Research that uses tax haven lists is inevitably compromised, showing at best a partial view. Tax haven lists matter – and so there’s a lot of political jockeying by tax havens to get off the blacklists. It is unfortunate, to say the least, that most economic analysis of tax-havenry has simply taken as read the politically-distorted identification.

The Tax Justice Research Bulletin won’t plug TJN’s own research very often. But the Financial Secrecy Index is one of the biggest research contributions the network has made. It adds the refreshing possibility of rigorous definition to the inevitable vagueness of debates on ‘tax havens’ (on which see e.g. my chapter in the World Bank volume); and it helps shifting views (and policy) away from seeing corruption as a poor country problem. The origin of the index lies in these two points.

The leading journal Economic Geography has now published our paper, which we hope will accelerate the ongoing process of its adoption into academic research. Here’s the abstract:

“Both academic research and public policy debate around tax havens and offshore finance typically suffer from a lack of definitional consistency. Unsurprisingly then, there is little agreement about which jurisdictions ought to be considered as tax havens—or which policy measures would result in their not being so considered. In this article we explore and make operational an alternative concept, that of a ‘secrecy jurisdiction’, and present the findings of the resulting Financial Secrecy Index (FSI). The FSI ranks countries and jurisdictions according to their contribution to opacity in global financial flows, revealing a quite different geography of financial secrecy from the image of small island tax havens that may still dominate popular perceptions and some of the literature on offshore finance. Some major (secrecy-supplying) economies now come into focus. Instead of a binary division between tax havens and others, the results show a secrecy spectrum, on which all jurisdictions can be situated, and that adjustment for the scale of business is necessary in order to compare impact propensity. This approach has the potential to support more precise and granular research findings and policy recommendations.

The ungated version of the research is published as a CGD working paper. We explain in some detail the definitional debates around the terms ‘tax haven’ and ‘offshore financial centre’, and the unresolved issues in each case that make them unsuitable for categories in research. In the case of tax havens, the impossibility of definition was most famously noted in a 1981 report to the US Treasury – yet it remains the most common term in research as well as media reporting. In policy, this has led to the use of subjective (and politically tampered-with) lists of jurisdictions, from the OECD, the IMF, and others.

Such lists reflect the politics of the creating institutions, and of the moment of creation, as well as the purpose. It is highly unfortunate, in terms of generating robust research findings, that economists in particular have tended to rely on such lists for their analysis of the effects of tax havens.

A similar dynamic affects the lists of “offshore financial centres” (OFCs); since everywhere (else) is arguably offshore, offshoreness lies in the eye of the beholder. Few deny the UK’s role in creating leading offshore financial markets; but few institutions have been willing to put the UK on their lists of OFCs. The United States is perhaps just as problematic. Once again, the absence of objectively verifiable criteria lead to a tendency to over-represent small jurisdictions, and to woolly research findings at best.

The alternative we propose is to focus on financial secrecy instead, defining ‘secrecy jurisdictions’ using objectively verifiable criteria (around e.g. banking secrecy, international tax cooperation, and corporate transparency), and combining this with a scale weighting based on each jurisdiction’s share of global financial service exports.

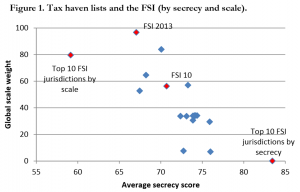

Figure 1 compares some FSI findings with the most commonly used lists (the blue diamonds). Two points can be seen clearly: first, most lists capture less than half of the global market (only one captures more of the market than the ten biggest jurisdictions); and second, most lists are a little more secretive than the FSI in general, or the top ten FSI jurisdictions (albeit not nearly as secretive as the ten most FSI secretive jurisdictions, which together account for c.0% of the global market).

Figure 1 compares some FSI findings with the most commonly used lists (the blue diamonds). Two points can be seen clearly: first, most lists capture less than half of the global market (only one captures more of the market than the ten biggest jurisdictions); and second, most lists are a little more secretive than the FSI in general, or the top ten FSI jurisdictions (albeit not nearly as secretive as the ten most FSI secretive jurisdictions, which together account for c.0% of the global market).

Scale matters; and so does objective analysis of secrecy. As the FSI is increasingly used in policy and research analysis, including political risk ratings and other indices, we hope to see the emergence of a much more rigorous evidence base on the effects and determinants of ‘haven’ activity. There’s nothing else out there like it.

Beyond the research, it’s also worth remembering that tax havens, or secrecy jurisdictions, or ‘offshore’ are political economic phenomena. Understanding what makes these places tick, politically speaking, helps us better understand many processes at the heart of financial globalisation. The Financial Secrecy Index also offers ways of thinking about this from a political economy perspective, here.

One last thing: with the launch of the 2015 FSI in November, we’ll be getting into a serious process of evaluation, which we expect to lead to some non-trivial changes in the construction of the index. If you’d like to weigh in on this, just drop me a line. (Or we may come and find you with a survey or interview request anyway…)

IMF: developing countries’ BEPS revenue losses exceed $200 billion

For as long as there has been civil society attention to issues of tax justice, there have been calls for the international financial institutions to provide analyses of the scale of various aspects of the problem. Raymond Baker has been particularly heroic in pursuing and prodding the World Bank and IMF to produce estimates of illicit flows to complement or challenge those of Global Financial Integrity. Long-term leader among bilateral donors, Norway even managed to seal a deal with Robert Zoellick to pay for his World Bank to produce such an estimate – until a senior Bank staff revolt led him to reverse course and deliver only a volume of work by outside authors.

While there are still no takers for estimates of the full breadth of illicit financial flows, the last year has seen a growing willingness to come up with big numbers for the scale of revenue losses due to the tax behaviour of MNEs. In addition to unpublished estimates by OECD researchers (I could tell you about this, but…), UNCTAD have prepared an estimate that one type of tax dodge (thin capitalisation via a small number of opaque jurisdictions) resulted in the manipulation of declared returns in developing countries, producing a revenue loss of around $100 billion p.a. (see also the critique suggesting the estimate should perhaps be nearer $300 billion).

The IMF – where the sole leadership of the OECD in the BEPS process still kinda rankles – has been increasingly active in this area. Its 2014 spillover analysis began by emphasising “the IMF’s experience on international tax issues with its wide membership”, and concluded with the finding that developing countries (i.e. those within the IMF’s remit but not the OECD’s) suffer from spillovers (i.e. tax losses due to behaiour of other jursidictions, and in particular revenue losses due to profit-shifting) that are “especially marked and important.”

In terms of the prospects for BEPS, the IMF was unequivocal:

“At issue here are deeper notions as to the ‘fair’ international allocation of tax revenues and powers across countries (which current initiatives do not address)” (p.12); and “Current initiatives, which operate within the present international tax architecture, will not eliminate spillovers” (p.35).

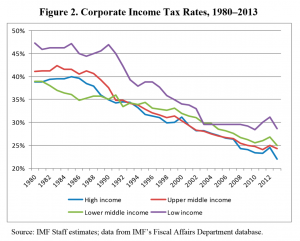

Strong stuff. And now researchers at the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Dept (FAD) have published a new study. Where the 2014 paper relied primarily on data on US MNEs, the currrent analysis uses the internal FAD dataset on tax revenues (unpublished, but thought to be not a million miles, at least in the approach used, from the ICTD Government Revenue Dataset). Figure 2 shows we’re on course for a near-halving of corporate income tax rates over 35 years.

The aim of the analysis is to understand the impact of CIT rates (domestic and foreign) on individual countries’ corporate tax base. The authors use the difference between ‘tax havens’ and non-havens to shed a little light on the relative importance of base effects that stem from shifting of real economic activity, as against profit-shifting. An interesting and important additional result, a ‘horse-race’ between the base effects of GDP-weighted and ‘haven-weighted’ tax rates of other jurisdictions, sees only the latter emerge as significant – suggesting “the primacy of avoidance over real effects” (p.18). Which is just TJN has long argued.

The aim of the analysis is to understand the impact of CIT rates (domestic and foreign) on individual countries’ corporate tax base. The authors use the difference between ‘tax havens’ and non-havens to shed a little light on the relative importance of base effects that stem from shifting of real economic activity, as against profit-shifting. An interesting and important additional result, a ‘horse-race’ between the base effects of GDP-weighted and ‘haven-weighted’ tax rates of other jurisdictions, sees only the latter emerge as significant – suggesting “the primacy of avoidance over real effects” (p.18). Which is just TJN has long argued.

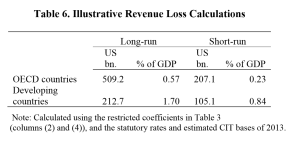

The authors also consider the question of the relative scale of effects between developing countries and OECD members (make of that choice of comparator groups what you will). Results for developing countries only suggest that both real effects and profit-shifting “matter at least as much”. And finally, a “simple, albeit highly speculative” revenue assessment produces table 6.

In line, as the authors note, with Gravelle’s (2013) study of US losses, they find a long-run annual revenue loss for OECD countries of toward 0.6% of GDP (some $500 billion). For developing countries however, the losses are nearly three times as high in GDP terms, exceeding $200 billion. This doesn’t immediately seem inconsistent with the UNCTAD findings of $100 billion lost through thin capitalisation alone – although it would certainly seem conservative if there is merit to the critique mentioned that revises this number towards $300 billion.

In line, as the authors note, with Gravelle’s (2013) study of US losses, they find a long-run annual revenue loss for OECD countries of toward 0.6% of GDP (some $500 billion). For developing countries however, the losses are nearly three times as high in GDP terms, exceeding $200 billion. This doesn’t immediately seem inconsistent with the UNCTAD findings of $100 billion lost through thin capitalisation alone – although it would certainly seem conservative if there is merit to the critique mentioned that revises this number towards $300 billion.

I’m hoping the authors are happy to share the code, and consider a couple of extensions. One could be to use actual effective rates from the US MNE data (which tend to show a sharper fall than other sources find); another to complement the tax haven list approach using the – ahem – Financial Secrecy Index.

Endpiece

Just one thing to flag this month – the imminent launch of the report of the Independent Commission on Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT).

I can’t say for sure what Joe Stiglitz and colleagues (economists, tax folks and others) from around the world will have made of their analysis of current tax rules, but it can only be useful to have a high-level, critical expert intervention. Those closed circles of tax professionals may be useful for channeling a certain policy convergence, but perhaps less so for the kind of wider thinking that may be needed.

As ever, submissions for the Bulletin, including musical offerings, are most welcome.

Related articles

Vulnerabilities to illicit financial flows: complementing national risk assessments

UN Submission: A Roadmap for Eradicating Poverty Beyond Growth

A human rights economy: what it is and why we need it

Strengthening Africa’s tax governance: reflections on the Lusaka country by country reporting workshop

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Incorporate Gender-Transformative Provisions into the UN Tax Convention

Just Transition and Human Rights: Response to the call for input by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

13 January 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

The Tax Justice Network’s most read pieces of 2024