John Christensen ■ The Tax Justice Research Bulletin – 1(1)

January 2015

The Tax Justice Research Bulletin is written by Alex Cobham

This is the inaugural Tax Justice Research Bulletin, the first of a monthly series dedicated to tracking the latest developments in policy-relevant research on national and international taxation. This issue looks at a new paper using the longest series of tax data that exist for any one country (challenges to this very welcome!), and an article on property taxation in Africa. The Spotlight section focuses on inequality and redistribution – including an important study from UN-DESA, Joe Stiglitz’s take on Piketty, and answers to that question you’ve been quietly pondering: just how much could you tax the 1%?

Its gotta be paid!

Welcome to the bulletin and best wishes for a justly taxed and well-researched 2015.

Lo-o-ng run tax data: Sweden, 1862-2013

Sweden’s IFN (the Research Institute of Industrial Economics) has undertaken a fascinating project, to bring together and analyse what seems to be the longest single-country span of tax data ever compiled. Published this month is the overview paper, by IFN researchers Magnus Henrekson and Mikael Stenkula. There’s a wealth of insight in it, and the individual papers that it draws upon, so I’ll just pick out a couple of points here.

Sweden’s IFN (the Research Institute of Industrial Economics) has undertaken a fascinating project, to bring together and analyse what seems to be the longest single-country span of tax data ever compiled. Published this month is the overview paper, by IFN researchers Magnus Henrekson and Mikael Stenkula. There’s a wealth of insight in it, and the individual papers that it draws upon, so I’ll just pick out a couple of points here.

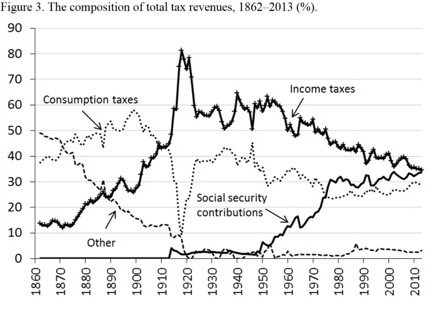

First, the Swedish system has seen major swings over time in both structure and scale. The authors identify three major stages: a low and stable tax-to-GDP ratio until around 1930, with consumption taxation the major component; sharply increasing tax-to-GDP to around 50% and then stable until 1990, with income taxes important, and VAT and social security contributions increasingly so; and then a declining tax-to-GDP ratio post the 1990–1991 reforms, with income taxes decreasing, wealth and inheritance and gift taxation abolished, and a growing relative reliance on consumption tax and social security contributions.

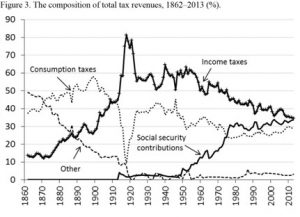

The second broad point that emerges very clearly is that the type of tax headings I’ve just used are not always helpful, especially in long-term analysis. The consumption tax revenue pattern in figure 3 conceals the same shift seen in most developing countries, albeit compressed into the last few decades, of customs duties being less than fully replaced by general consumption taxes (with possible though uncertain regressive impact). In Sweden’s case, there has also been a major reduction in revenues from ‘specific’ consumption taxes (sin and luxury taxes in particular).

The second broad point that emerges very clearly is that the type of tax headings I’ve just used are not always helpful, especially in long-term analysis. The consumption tax revenue pattern in figure 3 conceals the same shift seen in most developing countries, albeit compressed into the last few decades, of customs duties being less than fully replaced by general consumption taxes (with possible though uncertain regressive impact). In Sweden’s case, there has also been a major reduction in revenues from ‘specific’ consumption taxes (sin and luxury taxes in particular).

Two areas in which the research could be usefully extended are to consider the associated developments in inequality (see Spotlight below), and in political representation. The latter is a slightly odd omission, where the authors motivate the work by setting out the other four of the five Rs of taxation.

But this is quibbling, of course. The paper, and the project, represent exactly the type of work that, as Morten Jerven has pointed out, is necessary to complement the improvement in cross-country data represented by the ICTD’s Government Revenue Dataset. It would be valuable for the authors to share further details on the process and resource demands of the project, as an input to others considering the same in other countries.

Property tax and state-building

Property tax and state-building

In a new article for the Africa Research Institute, ‘How Property Tax Would Benefit Africa’, Nara Monkam (ATAF) and Mick Moore (ICTD) provide a useful overview of the current state of play, while making the case for a greater role for property tax – not least because of its potential in respect of accountability. Unsurprisingly, the continent contains a ‘spaghetti soup’ of different approaches to property tax, operated by various tiers of government, and with widely varying revenue importance. The ‘soup’ includes specifically land value taxes (LVT), as well as those focused on buildings, and many combinations thereof.

Two complementary avenues for improvement are identified. Investment in administrative capacity, most obviously through (re)building cadastres, digitising ownership records and harmonising with other databases such as utility company records, is vital. (And far from being a low-income country problem only – see for example Andy Wightman’s sweeping work on Scottish land, The Poor Had No Lawyers).

But also necessary is a hefty dose of political will.

The authors compare 3 Sierra Leone city councils to illustrate the point:

In Bo, 93% of business owners surveyed in 2012 were able to produce a property tax receipt and 87.5% believed that local elites were successfully prosecuted for non-compliance.

In Makeni and Kenema, however, only around 40% were able to produce a receipt, and just 30% were confident of successful prosecution. All three cities had demonstrated rapid revenue gains, but in Makeni and Kenema annual increases stagnated as elites proved resistant to the tax, while the municipal authorities in Bo made further progress due to sustained political will.

Monkam and Moore conclude: “The future of African national and municipal governments will depend on institutions and tax policy that are equitable, improve local service delivery and encourage compliance through establishing a social contract between taxpayers and the state. Property tax is one of the more effective means of realising these goals.”

I tend to agree, though we’re still short of definitive evidence for that last statement. In some ways this article highlights the dearth of rigorous research on which to draw – but it’s certainly building, and the case for greater research focus (at least) on property tax is clear.

One area of particular caution: there is evidence that property taxes at sub-national levels are often regressive (see e.g. ITEP’s report this month on the US), albeit less so than consumption taxes. Issues of political commitment therefore go beyond whether elites comply or not, to whether a progressive design (quite possibly LVT) can be put in place and maintained.

Spotlight: Redistribution, assets and inequality

Talking of progressive… UN-DESA’s Pierre Kohler has produced a really useful and broad – yet far from shallow – overview, ‘Redistributive Policies for Sustainable Development: Looking at the Role of Assets and Equity’.

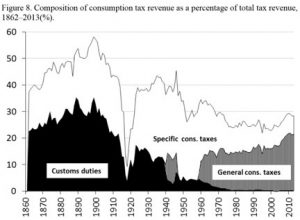

Part of the basis is figure 3 on the left, which shows the extent to which redistribution has remained relatively static in the facing of rising market inequality – leaving final inequality to mirror that rise. But Kohler’s real focus is on the distinction between stock inequality (in e.g. land and capital), and flow inequality (in derived income streams).

Part of the basis is figure 3 on the left, which shows the extent to which redistribution has remained relatively static in the facing of rising market inequality – leaving final inequality to mirror that rise. But Kohler’s real focus is on the distinction between stock inequality (in e.g. land and capital), and flow inequality (in derived income streams).

The paper draws on the work of Piketty and related researchers, and the main distributional databases, to establish the base from which a relatively comprehensive analysis of main policy areas is then constructed. Some of the tax results I would like to see reworked with the ICTD data for robustness and broader coverage, but the overall effort is impressive and well worth the time to absorb, including treatments of wealth tax and unitary taxation for TNCs.

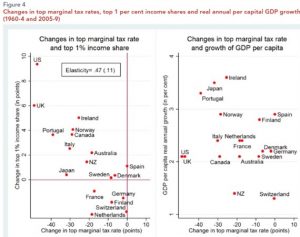

The paper also goes beyond the increasingly criticised Gini measure of inequality, making me happy with references to the Palma ratio and also covering some of the literature on the top 1%. The latter’s correlation with top marginal tax rates, and the absence of  correlation between those rates and growth, is striking. Indeed, it begs the question, how highly could the top 1% be taxed without negative economic effects?

correlation between those rates and growth, is striking. Indeed, it begs the question, how highly could the top 1% be taxed without negative economic effects?

A life-cycle model published last year concluded that “significant welfare gains [arise] from increasing top marginal labor income tax rates above 80%… and that these gains outweigh the macroeconomic costs” (Kindermann & Krueger, 2014: 19). As the authors note in a shorter comment, the results do not allow for avoidance behaviour; but, they argue, if this was constrained in the real world, then a Piketty-esque wealth tax would be unnecessary because a top marginal income tax rate of 80%-95% would do the job.

Of course, Piketty’s own paper (with Saez and Stantcheva) does allow for avoidance, and uses detailed empirical work on elasticities to find that the revenue-maximising top tax rate for plausible scenarios ranges between 62% (full tax avoidance scenario, where any e.g. policy-led reductions in avoidance change the elasticities and raise the optimal tax rate) and 83%.

Finally, Joe Stiglitz has taken on Piketty from a progressive perspective, arguing that the latter’s analysis of growing wealth concentration fails to capture a major part of the dynamic: not increases in capital but rather rises in the value of existing assets urban land, driven by factors outside the owners’ control (i.e. rents). [I have a hard copy of the paper from December’s fantastic Columbia conference, and it is referenced in interviews – but I haven’t found a published version online yet; will link when I do.]

Endpiece

Thanks for reading. This is the first Tax Justice Research Bulletin and it’s a work in progress – so any comments on the format, content etc, or suggestions for future research to include, would be most welcome.

If you played the song linked at the top while you read through, and it inspired you to think of tax songs for future bulletins, send them on over! And please don’t hesitate to pass this bulletin on to colleagues working in the field.

Related articles

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The myth-buster’s guide to the “millionaire exodus” scare story

Money can’t buy health, but taxes can improve healthcare

The elephant in the room of business & human rights

UN submission: Tax justice and the financing of children’s right to education

14 July 2025

You should listen to the Beatles ‘The Taxman’. Faced with a 95% tax rate on their incomes in the UK the band left the country and paid nothing to the HMRC.

You can also study the heavy weight boxing championship in years with high tax rates. You will see they limited the fights to limit income / year so as to avoid the high rates.

People won’t work. It’s well documented. In progressives dreams people earn a dollar and keep a nickel. In the real world they pay zero tax by either not working or working in another country.

Thanks Neill. Maybe we’ll try that next month! We’ve had a few other suggestions for the list too. On the substantive point, it’s really not well documented that people won’t work at higher tax rates – in fact, we have a good deal of evidence that economies roll along very smoothly with high top marginal tax rates. Do check out the papers in the bulletin, and the wider literature they refer to – both theoretical and empirical.