Andres Knobel ■ The G20 and the OECD disappoint again

We recently published an optimistic blog post about the advances made at the OECD’s annual Global Forum meeting that took place on 22 November 2018. Now, less than 10 days later, the OECD has submitted a report to the G20 and the G20 have issued a Communiqué that together bear some disappointing news.

First, the G20’s Communique.

We thought it was hard for a non-binding communiqué that superficially refers (in just one paragraph) to all relevant issues on tax and financial transparency to get any worse. We were wrong.

The G20’s 2017 Communique made these positive remarks about automatic exchange of information and beneficial ownership:

We look forward to the first automatic exchange of financial account information under the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) in September 2017. We call on all relevant jurisdictions to begin exchanges by September 2018 at the latest (…)

As an important tool in our fight against corruption, tax evasion, terrorist financing and money laundering, we will advance the effective implementation of the international standards on transparency and beneficial ownership of legal persons and legal arrangements, including the availability of information in the domestic and cross-border context (…) [emphasis added]

(That we considered these remarks to be positive gives you an idea of how low our expectations were)

One could argue that the US was implicitly covered in the call “on all relevant jurisdictions” to start implementing the Common Reporting Standard for automatic exchange of information. In addition, it was important that the G20 recognized the importance of beneficial ownership transparency for both companies and trusts to tackle corruption, tax evasion and money laundering. Arguably, this applied to the US and to many other G20 countries where beneficial ownership isn’t even available. Argentina, which held the G20 presidency in 2018, not only failed to keep the status quo set by these remarks but actually made its own corporate transparency worse. Only the EU could be said to have made progress on this issue.

The G20’s 2018 Communiqué now seems to be backpedaling on its previous Communique. The new declaration removed the call on relevant jurisdictions to start automatic exchanges and erased all references to beneficial ownership. In place of these calls, the 2018 Communiqué merely welcomes the:

“…commencement of the automatic exchange of financial account information and acknowledge the strengthened criteria developed by the OECD to identify jurisdictions that have not satisfactorily implemented the tax transparency standard.”

We’ll get to the supposedly “strengthened” criteria put forward in the OECD’s report to the G20 in a minute, but there’s another shortcoming in the Communique. Out of the blue, the G20 took a big step backwards in the fight against tax avoidance:

“We will continue our work for a globally fair, sustainable, and modern international tax system based, in particular on tax treaties and transfer pricing rules” (emphasis added)

Not only has the G20 toned down or erased recognition of the most important tools available today for tackling tax evasion, corruption and money laundering, it has specifically given recognition to the very mechanisms that can be abused to enable tax evasion, corruption and money laundering.

We wonder if this is a response to our welcoming of the IMF questioning the sustainability of the arm’s length principle while exploring unitary taxation, only a few months earlier. Or to the long list of recent publications on how tax treaties can negatively affect developing countries.

The Communiqué published in Buenos Aires has failed to comply with a popular Spanish expression “Si no suma, que no reste” (if it won’t add value, at least it shouldn’t take it away).

Now, back to the usual suspect: the OECD.

Based on the OECD’s “strengthened” criteria which it put forward in its new report to the G20 (just imagine what the weaker version looked like!), jurisdictions should comply with two out of three requirements and avoid the two immediate triggers to prevent being blacklisted. If they fail on any of the immediate triggers, they will be blacklisted even if they comply with the two of the requirements. The three requirements are

- Obtaining at least a “largely compliant” rating from the Global Forum peer reviews on exchange of information on request (EOIR). A “non-compliant” rating would “immediately trigger” being blacklisted.

- Implementing automatic exchange of information (AEOI) pursuant to the OECD Common Reporting Standard (CRS). Not implementing the CRS if the jurisdiction committed to doing it would “immediately trigger” being blacklisted (The condition in this trigger clause seems to primarily just benefit the US who never committed to the CRS in the first place. In any case, this seems to be more sensible than exempting a country just because it’s located between Canada and Mexico or makes good apple pie!),)

- Having the Multilateral Convention on Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (aka the Multilateral Tax Convention) in force, or a sufficient network of bilateral treaties that allow exchanges on request and automatic ones.

Thanks to the OECD’s report to the G20 we know that the OECD blacklist based on the new strengthened criteria isn’t ready yet, but we can deduct which 15 jurisdictions are at risk of being identified.

It also helps to compare these 15 jurisdictions, with the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index’ top 15 ranked jurisdictions:

The Financial Secrecy Index ranks jurisdictions according to the “worst offenders”, meaning those who are mostly responsible for global financial secrecy and which, if they became transparent, would have a positive and tangible impact on reducing financial secrecy in the world. This would clearly be the case for the US, Switzerland, Cayman Islands, Hong Kong, Singapore, Luxembourg, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon and Panama among others. These top 15 jurisdictions on the Financial Secrecy Index account for 62 per cent of the global market of offshore financial services. On the contrary, the 15 jurisdictions at risk of being blacklisted by the OECD (mostly small islands) account for only 0.64 per cent of the global market of offshore financial services. In other words, if the 15 jurisdictions at risk of being blacklisted by the OECD became fully transparent, it would be hard to tell the difference at a global level, given that they account for less than 1 per cent of the global offshore financial services. The 15 jurisdictions at risk of being blacklisted by the OECD provide almost 100 times less offshore financial services than the 15 jurisdictions identified by the Financial Secrecy Index.

Moreover, these 15 jurisdictions at risk of being blacklisted by the OECD, don’t really need to become fully transparent to be off the hook. Small improvements will do.

Here are all the changes the 15 jurisdictions need to undertake to avoid the blacklist:

- Dominica, Israel, Montserrat, Niue, Russia and St. Vincent only failed the “immediate trigger” on automatic exchange of information (AEOI). They committed to start implementing the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for automatic exchange of information in 2018 but haven’t done so yet. Once they start exchanging, they’ll be safe.

- Anguilla, Marshall Islands, Sint Maarten and Turkey are rated “partially compliant” by the Global Forum, which falls below the minimum requirement of “largely compliant”. More crucially, they have not implemented their commitment to the automatic exchange of information, thus triggering immediate backlisting. Because these jurisdiction already meet the requirement of having the Multilateral Tax Convention in force, they would only need to start automatic information exchanges (to meet the immediate trigger) to be safe from the blacklist. While they could also improve their rating to at least “largely compliant”, they don’t really need to because by implementing automatic exchanges, they would already be complying with two out of the three requirements, including both immediate triggers.

- –Antigua and Barbuda, Brunei, Qatar and Vanuatu failed the immediate trigger for not implementing their commitment to automatic exchange of information commitment and they do not have the Multilateral Tax Convention in force. While they are all “largely compliant” regarding exchanges on request, they won’t be able to engage in automatic exchange of information to meet the immediate trigger unless they also sign and ratify the Multilateral Tax Convention.

- –Trinidad and Tobago is the only jurisdiction that needs to make some big changes. In addition to starting automatic exchanges (so as not to keep failing on the immediate trigger for not implementing their AEOI commitment), Trinidad and Tobago will also need to improve its Global Forum rating on exchange of information on request because its current “non-compliant” rating is another immediate trigger. In other words, even if they start implementing the automatic exchange of information, unless they improve their compliancy rating, they will still be blacklisted,). However, in order to start automatic exchanging information, they will also need to become a party to the Multilateral Tax Convention. On the bright side (for Trinidad and Tobago, not for global transparency), once this Caribbean island signs and ratifies the Multilateral Tax Convention and starts implementing automatic exchange of information, they will only need to improve their Global Forum rating to a “partially compliant” and still be white-listed.

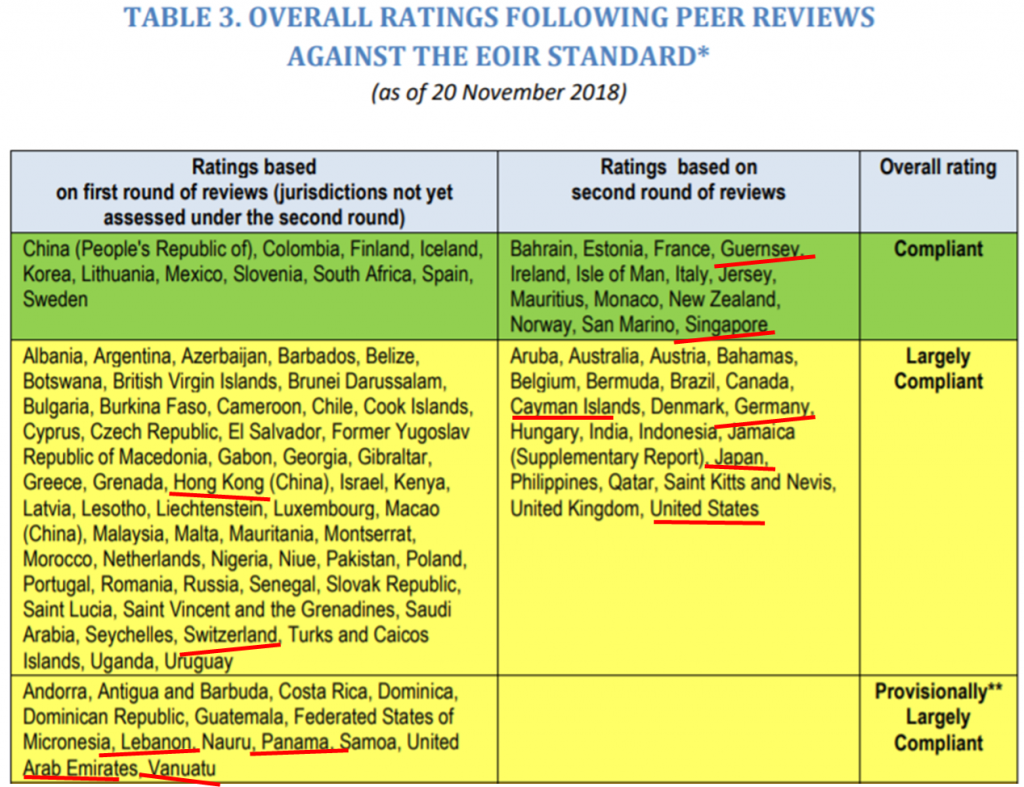

The Global Forum ratings

Obtaining a “largely compliant” rating is one of the three factors needed to avoid the blacklist. How hard is it to achieve it? Not that difficult, as long as you are a powerful country. If you don’t believe it, just look at the number of countries considered “compliant” and “largely compliant” by the Global Forum:

Source: 2018 OECD report to the G20 (red underline added)

The vast majority of members of the Global Forum are considered to be “compliant” and “largely complaint”, including the worst offenders on the Financial Secrecy Index (underlined in red).

We wonder which rose-tinted glasses the Global Forum is looking through at the world of transparency and how they can ever explain the likes of the Russian Laundromats and other cases of grand corruption given how perfectly transparent their world appears to be.

Other organisations, including the Tax Justice Network, are not as optimistic at the Global Forum. Let’s take a look.

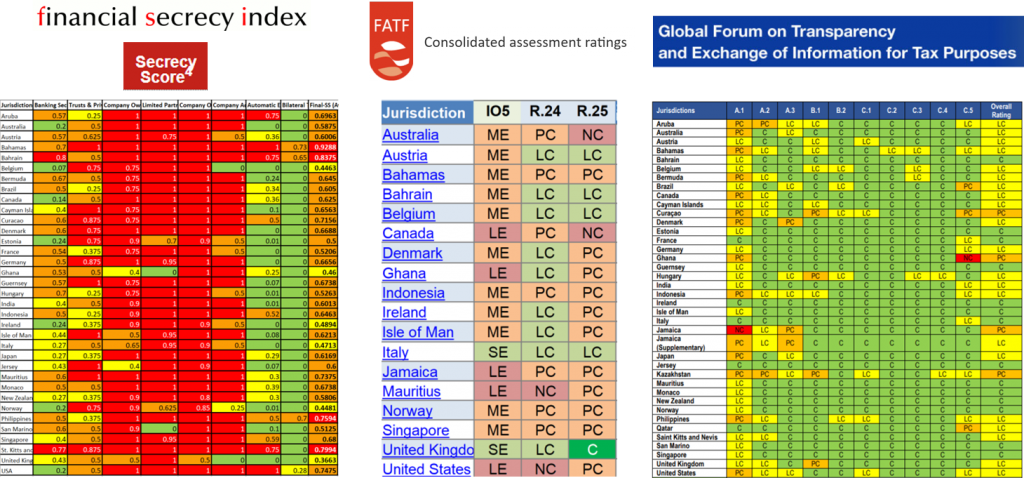

The OECD report to the G20 includes a colour-coded table showing the ratings of 39 jurisdictions from the second round of peer reviews against the exchange of information on request (EOIR) standard. This table, reproduced below, refers to the three sections (A, B and C) of the peer reviews that assess availability of ownership information and accounts, access to information by authorities and exchange of information.

Given that many organisations apply the same traffic-light colour coding (green = transparency; yellow = partially secretive; orange= largely secretive; red = fully secretive), we can compare colour composition of the Global Forum’s transparency table to the colour composition of the Financial Secrecy Index’ Secrecy Score and the Financial Action Task (FATF) 4th round of mutual evaluations on compliance with anti-money laundering recommendations.

To make it comparable, we only focus on the 39 jurisdictions assessed by the Global Forum’s second round of reviews that have also been assessed by the Financial Secrecy Index and the FATF. We only show the colour ratings of indicators from the Financial Secrecy Index and the FATF that are relevant to the Global Forum’s second round of review. In the case of the Financial Secrecy Index, these are indicators 1 to 3, 5 to 7, 18 and 19 on ownership information, accounts, banking secrecy and exchange of information. In the case of the FATF, these are recommendations 24 and 25 on availability of beneficial ownership information and effective implementation of these recommendations (Immediate Outcome 5).

This is what the ratings for the same jurisdictions (where available) look like according to each organisation:

Both the Financial Secrecy Index and the FATF have overall much more red, orange and yellow (the FATF uses light green in place of yellow) especially with regard to ownership information (the first six columns of the Index and all three columns of the FATF). While the Global Forum overall has more green (aka compliance), the Global Forum’s first column (on availability of ownership information) does show much more colour diversity and less green. Nevertheless, the Global Forum’s last column, which shows the overall rating, is the one that matters for the OECD blacklist, and in this case, the vast majority of countries are “compliant” (green) or “largely compliant” (yellow).

In conclusion, we would love to live in the world portrayed by the G20 and the OECD, where most countries are fully transparent (including all major financial centres) and where some automatic exchange of information among some countries, tax treaties and the arm’s length principle are enough to tackle all illicit financial flows (including tax avoidance). However, we happen to live in a world where illicit financial flows are alive and kicking, in many respects thanks to the G20,OECD countries and their dependencies that fail to implement real transparency and instead engage in a race to the bottom offering less regulation, less taxes and less questions asked when it comes to accepting non-residents’ money.

Related articles

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

When AI runs a company, who is the beneficial owner?

Insights from the United Kingdom’s People with Significant Control register

13 May 2025

Uncovering hidden power in the UK’s PSC Register

New article explores why the fight for beneficial ownership transparency isn’t over

Asset beneficial ownership – Enforcing wealth tax & other positive spillover effects

4 March 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024