Idriss Linge ■ Glencore and Sinosteel cases in Cameroon: Practical cases of the need for more transparency on extractive contracts in Africa

A mining contract signed by the Government of Cameroon with Sinosteel, a Chinese multinational, for an iron ore project was the centre of controversy in May 2022. Parliamentarians and some activists denounced the contract and demanded its cancellation because the agreement was disadvantageous for Cameroon. In an interview with BBC Africa, the Cameroonian mining minister swept aside all concerns, and the government decided to publish the contract online.

In the same month, Glencore, the Anglo-Swiss multinational that dominates commodities trading, admitted to paying USD $79.6 million through front companies to obtain advantageous oil and gas contracts, including in Cameroon.

These are reminders that people need to know more about the agreements that give foreign companies the right to exploit and trade resources belonging to their countries. State coffers and therefore citizens, always lose out because of hidden deals, weak laws and aggressive corporate tax practices. In most jurisdictions, non-renewable mineral resources are managed by the state on behalf of the people. States typically grant companies the right to explore, extract and often sell mineral resources in exchange for revenue or a share of production. Contracts describes the rights, duties and obligations of both companies and the state, including the fiscal regime. These contracts can span decades and have significant and lasting impacts.

Extractive contracts: why transparency matters

Contract transparency in the extractive industries is essential for fighting against illicit financial flows. In its 2022 Progress Report, the global Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) stated: “By shedding light on the rules and terms that govern extractive projects, contract transparency can help fight corruption and empower citizens to assess whether they are getting a fair deal for their resources. This information can be crucial in contexts where valuable revenues are impacted by market volatility and emerging energy transition policies”.

Contract disclosure means that officials and companies will be subject to increased scrutiny. This can deter contacts with weak or poor fiscal terms. It also allows governments to compare the quality of contracts with other jurisdictions. Disclosure allows government agencies other than the agencies that formally enter the contract, and civil society, to monitor contract compliance.

Opacity increases the risk of revenue loss. In a report published in 2021, the International Monetary Fund shows how the budgets of sub-Saharan African countries have been severely constrained by efforts to manage the Covid-19 pandemic, while tax avoidance by multinational extractive companies is costing them up to $750 million a year.

In 2021, the Tax Justice Network, Public Service International and Global Alliance for Tax Justice’s State of Tax Justice report found that Africa had lost USD $17.1 billion, mostly to multinational tax abuse. For the region, this represented the equivalent of a third of public health budgets in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Disclosure of extractive contracts: global and African trends in the Financial Secrecy Index 2022

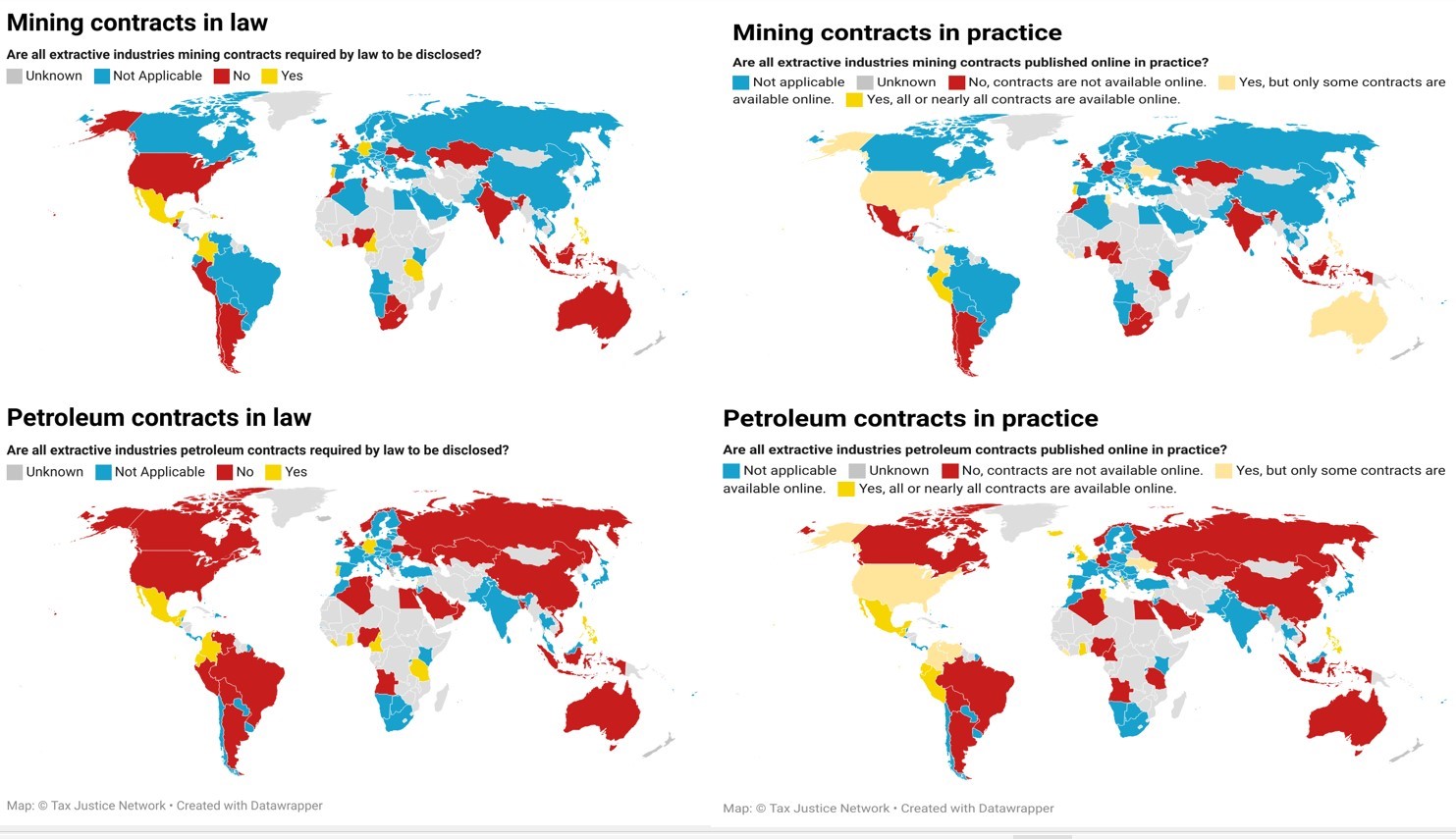

In the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index 2022, jurisdictions are assessed for contract transparency. Secrecy Indicator 9 examines whether domestic laws provide for online access to mining and petroleum contracts signed between governments and extractive companies.

To verify this, the index examines several levels of transparency in mining and petroleum contracts. Perhaps the most important aspect is whether a jurisdiction has adopted a law that requires the publication of all extractive contracts without exception. Yet policy is only as good as practice. The analysis reviews whether contracts are actually published. Countries are given scores depending on the level of disclosure in practice, ranging from all/most contracts being made public and accessible, to no contracts being disclosed online. For the collection and analysis of information, the Financial Secrecy Index uses the most recent update of the Natural Resources Governance Index (oil and gas) contract disclosure tracker, maintained by the Natural Resources Governance Institute.

Of the 141 countries analysed by the Financial Secrecy Index 2022, 29 are considered mining countries and 47 are oil producing countries. Of the mining, only 9 have adopted laws that mandate the disclosure of mining contracts, three of which are in Africa (Cameroon, Liberia and Tanzania). With regard to oil contracts, 12 countries, including 4 in Africa (Ghana, Cameroon, Tanzania and Liberia), have laws requiring contract disclosure.

Fewer countries actually publish contracts in practice. Of the 29 mining countries, only 4 publish all of their contracts, 7 do so partially, 17 do not do so at all and for 1 country this information has not been cross-checked. In petroleum, 12 countries publish contracts, 6 publish only some contracts, and 27 do not publish at all (2 countries could not be confirmed).

Source: Financial Secrecy Index 2022

In Africa, of the 18 countries in the region assessed by the Financial Secrecy Index, 9 have oil, and only 2 (Ghana and Tunisia) publish all their oil contracts. Liberia publishes some contracts and countries like Nigeria, Angola, and Algeria, which are the three largest oil producers in the region, do not publish contacts at all. In the mineral resources sector, no country fully publishes its contracts. Two countries, notably Liberia and Tunisia, publish some contracts and seven African mining countries do not publish any contracts.

Based on this analysis, it can be concluded that Liberia is an example of good practice in Africa in terms of disclosure of extractive resource contracts. Even if it only publishes some of its contracts, the authorities have passed laws that require the publication of mining and oil contracts. Tunisia does not have specific laws for disclosure but it publishes its extractive contracts. While Ghana is a historical gold producer in Africa and has no contract disclosure for mining, it has recently passed a law that provides for publishing oil contracts.

Cameroon has made progress, but needs to catch up with best practice

For Cameroon, the Financial Secrecy Index 2022 shows that the law favours the publication of extractive contracts. Indeed, according to Article 6 of Law 2018/011 on transparency and good governance in the management of public finances, “Contracts between the administration and public or private companies, particularly companies exploiting natural resources and companies operating public service concessions, shall be clear and made public. These principles apply both to the procedure for awarding the contract and to its content”.

Despite the existence of this law, Cameroon has not been rated highly on the publication of contracts by the Financial Secrecy Index 2022. At the time the index was published, and despite exchanges with the Cameroonian authorities, no evidence was provided that the country is publishing its oil and mining contracts. In its new National Development Strategy, the authorities have placed the extractive sector (gas and solid minerals) as a lever for its development in the second part of its Vision 2035. There is also no publicly accessible platform where the different licenses/contracts on extractive operations can be found.

Following pressure from the public after the initiative of a parliamentarian, the Ministry responsible for mining decided to publish the mining contractof iron ore with the Chinese state group Sinosteel. An analysis of this contract reveals that some of its provisions are contrary to the spirit of the law on transparency and good governance in Cameroon, and it also falls short of the transparency standards promoted by the Tax Justice Network, Tax Justice Network-Africa, the Natural Resources Governance Institute, the global Publish What You Pay coalition, as well as other civil society actors who advocate for greater transparency in the sector. Article 27 of this document states that certain information on the execution of the mining contract is confidential and cannot be made public. Further, article 44 provides for the possibility of negotiating special agreements, which are not integrated into the main contract and are not made public. These provisions are likely to favour the company, to the detriment of the interests of the Cameroonian people and the populations living near the mine. Secret negotiations could also negatively affect the government’s ability to generate consistent revenue from the exploitation of the resource.

Transparency in headquarter jurisdictions

The issue of transparency of extractive contracts is key to reducing tax abuse in Africa and all developing countries. Many jurisdictions are not necessarily endowed with natural resources, but are home to multinational companies active in the sector. These include European Union countries as a whole, and countries such as Switzerland. France and Italy, for example, are home to several of the world’s leading energy companies, including Total, Areva, and ENI, which have mining and hydrocarbon operations in Africa. The European Parliament and Council adopted the directive on accounting and transparency in 2013, which obliges mining, oil and gas companies and logging companies above a defined size to report their payments to the respective governments of the countries where they operate. All 27 Member States have transposed this directive into their national laws.

On 19 June 2020, the Swiss Parliament revised its Code of Obligations relating to company rights and new provisions require Swiss extractive companies active in oil, gas and minerals to disclose payments they make to governments around the world. This law is aligned with the extractive industries rules already in place in Canada, the European Union, Norway and the United Kingdom. The law applies to companies’ extractive activity for payments above 100,000 Swiss francs per year and runs from 1 January 2021.

While important, these advances represent only a small part of the need for full transparency in extractive contracts. Mining and oil companies are also cited as supporting at the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. The International Council of Mining and Metals Companies has also indicated that all of its members are in favour of greater transparency in extractive contracts, and are aligned with the implementation of the EITI principle .

Transparency is necessary, but not sufficient

Yet advances remain limited where the objective is to fundamentally reduce abuse in the extractive industries. The EITI standard on contract transparency, for example, only applies to contracts signed after 1 January 2021. In Africa, the bulk of contracts are more than 30 years old. And as the Financial Secrecy Index shows, while many countries adopt laws for contract disclosure, in practice, many countries do not publish at all, or only some contracts. Further, once contracts are published, other essential elements such as updates on beneficial owners, contract annexes, environmental management, project financing, and subcontracts are not made public.

The Africa Mining Vision, which has been adopted by all African countries, also places an emphasis on transparency across the mineral value chain, alongside deep economic structural changes to ensure resources work for the people. In particular, the Africa Mining Vision states that laws should allow for a clear understanding of the people behind multinational extractive companies and their projects. Contracts must also be approved by parliamentarians.

Further, to promote fiscal transparency in the extractive sector and tackle illicit financial flows:

- Countries need to rapidly put in place a framework that ensures greater transparency on the exploitation of extractive resources, to enable their tax administrations to access better information and collect more revenues. Tax authorities and other oversight institutions should be involved in the awarding and implementation of these agreements.

- Countries should require multinationals to report periodically on any tax avoidance schemes they use.

- Countries should adopt laws that ensure the availability of information on the beneficial owners of all legal entities. This information should be updated and verified.

- Capital gains must be effectively taxed, so that, for example, when junior exploration companies sell rights, often through offshore structures, profits are not shifted.

- Countries should publish all tax expenditures related to the extractive industries with clear policy goals and evaluate their effectiveness.

- Production transparency and monitoring is necessary to prevent under-declarations which can undermine the collection of royalties and be used to shift profits out of the source country.

- Contract transparency must go beyond the primary contracts. It should be applicable to the agreements that are signed along the supply chain, paying particular attention to intermediaries (subcontractors, traders and others). They should be subject to contract transparency, and also to the same requirements of fiscal transparency and different anti-money laundering legislation.

Related articles

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

The State of Tax Justice 2025

Follow the money: Rethinking geographical risk assessment in money laundering

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

The “millionaire exodus” visualised

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025