Nick Shaxson ■ Tax havens meet monopoly power: why national competitiveness harms competition

This article is cross-posted from The Counterbalance, the newsletter of the Balanced Economy Project, a new organisation dedicated to tackling monopolies and excessive market power. It has been slightly adapted for the Tax Justice Network’s blog.

Today we focus on the strange concept of national competitiveness – the ‘competitiveness’ of countries or states (rather than of companies in a market.) “Our nation must be competitive!” politicians and pundits love to cry. “We need a competitive tax system!” It sounds wonderful. Who would want to be uncompetitive?

But what does this concept mean? Is a competitive tax system really a good thing? What about competitive financial regulations, or competitive labour laws? Or, oddest of all, what might “competitive” competition policy look like?

There is more than one possible answer, but in many countries a “Competitiveness Agenda” holds sway. The idea here is that money flits easily across borders, so states must lure it with shiny baubles such as low taxes, financial secrecy, slack financial regulations, low wages, subsidies & incentives, merger- and monopoly-friendliness – and generally weak enforcement. Tax havens are where this agenda has been followed to the maximum.

Yet any well-trained economist will tell you that the agenda rests on elementary fallacies and woolly thinking. If taxpayers must hand out sugar-coated subsidies to attract investors, is the trade-off worth it, what kinds of investors will come, and will other states respond, engaging in a race to the bottom to bring us back to square one? (Today’s Counterbalance author, Nicholas Shaxson, who also works part-time for the Tax Justice Network, has just written an article for Foreign Affairs looking at the international tax dimensions of this, and at a clear-headed new approach from the Biden administration.)

The competitiveness agenda looms largest for countries outside the US, because in smaller economies, cross-border trade tends to form a larger share of the economy, thus making international “competitiveness” more relevant for them.

We’ll focus quite heavily on Britain, where this agenda has long had influence and seems in the ascendancy again after Brexit. We’ll take some detours into tax, tax havens and finance to unpack basic principles, before honing into ‘our’ area – monopoly power and competition. Here, our conclusion will be simple: the dominant vision of “national competitiveness” reduces (and corrupts) competition.

A brief historical aside. The Balanced Economy Project was sparked in 2020 after Michelle Meagher, a competition lawyer, read a long 2019 article I wrote for the Tax Justice Network about the links between tax havens and monopoly power, and asking why there was no coherent anti-monopoly movement outside the United States. We agreed to work together to try and catalyse something: this newsletter, among other things, is the result.

Competitiveness against competition

Last December the Tax Justice Network commented on a Britain’s Times newspaper article about inaccuracies in the popular Netflix series The Crown, leading some royal-obsessed Brits to call for tighter regulation.

Netflix is covered by a EU-wide regime that allows companies to go ‘forum-shopping’ to find the friendliest regulator (or “lead supervisory authority”). Inevitably, some EU countries, in turn, seek to lure the giants to set up their regional headquarters locally by giving them an easy ride on supervision, in the name of . . . “competitiveness.” Netflix chose the Netherlands, whose regulator, at the time the Times article came out, had “not investigated a single complaint from a British viewer” about it, and a prominent Conservative, Julian Knight, accused Netflix of using the Netherlands as a “flag of convenience” to escape regulation.

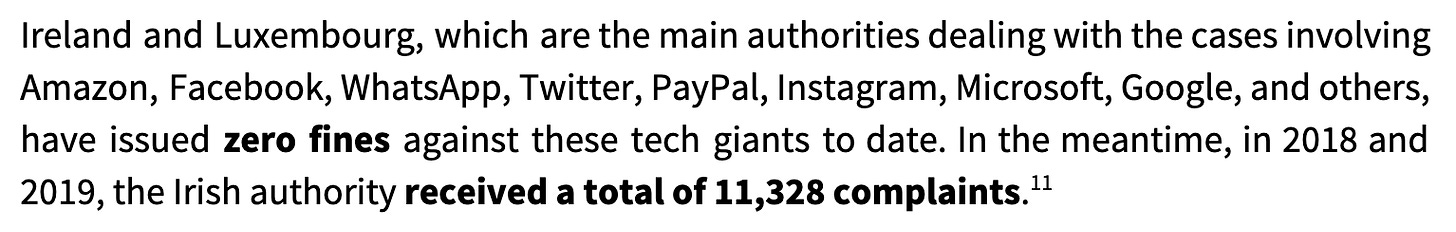

The Netherlands isn’t alone, as the digital watchdog Access Now noted:

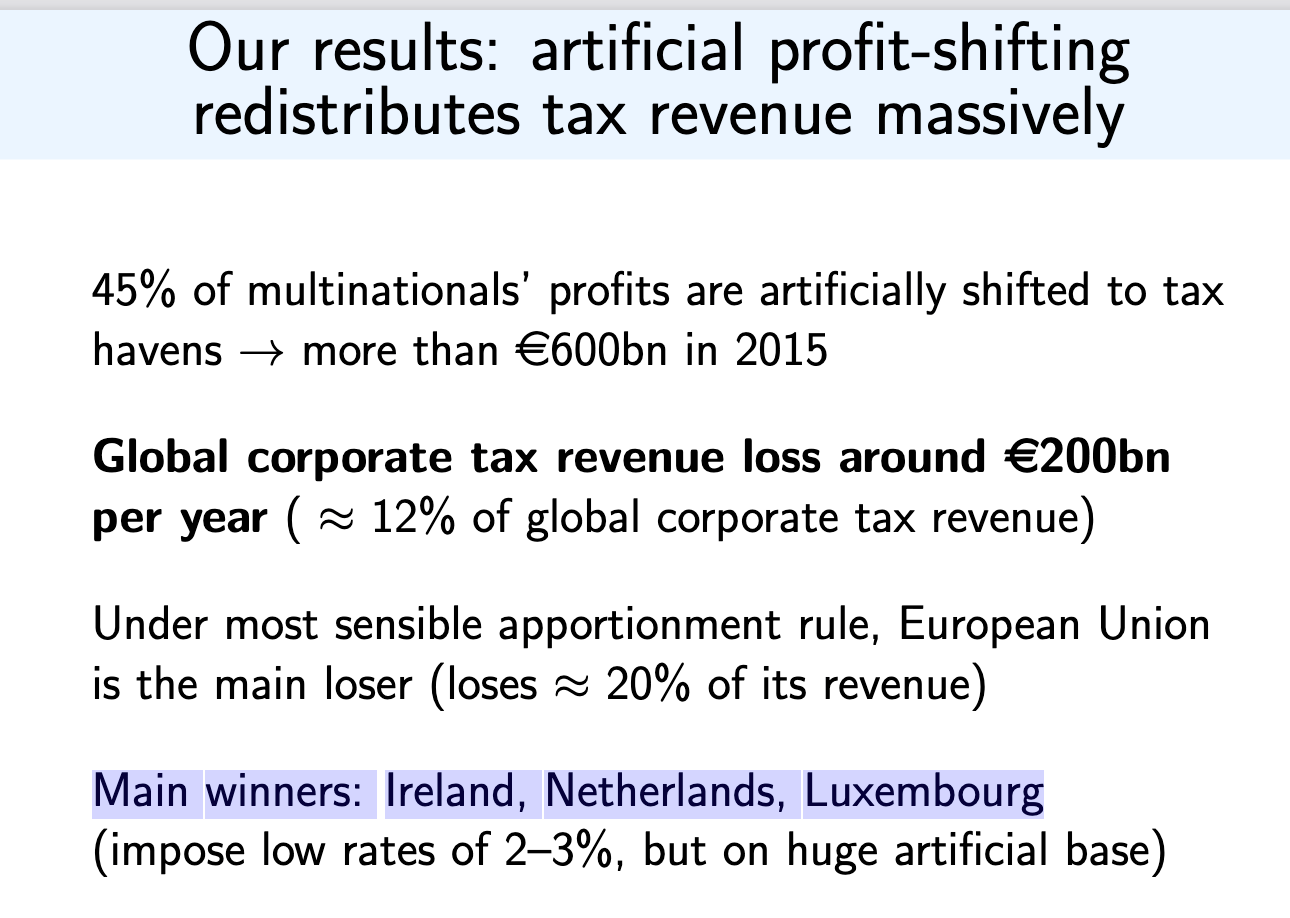

Why Ireland, the Netherlands and Luxembourg? A 2017 presentation about tax havens, by the French economist Gabriel Zucman, suggests an answer:

Our emphasis added. Those three countries are major corporate tax havens: each competes on offering multinational firms an easy ride not just on tax, but also on privacy rules, enforcement, and other lures to encourage multinationals to locate business activity there. In small countries it is relatively easier to capture and influence the legislature, the politicians, the media, and the zeitgeist. A race to the bottom on standards ensues.

These “competitive” processes undermine the very foundations of globalisation theory. Capital and investment was supposed to flow to where it is most productive, but instead, it gets redirected to where it can obtain the greatest subsidies, thus discrediting capitalism and globalisation.

To those of us familiar with tax havens, this “competitive” game is offshore business.

The offshore tax haven connection

Nobody agrees what a tax haven is, but their national economic strategies go far beyond tax. In my 2011 book Treasure Islands I define tax havens using two words, ‘escape’ and ‘elsewhere.’ You shift your money or business elsewhere – offshore – to escape rules and taxes you don’t like. Countries compete to attract it. That broad definition encompasses many fields: tax (of course); secrecy (here’s a ranking;) tolerance of financial crime (here’s the Financial Times calling Luxembourg “a criminal enterprise with a country attached”); data use (there’s a term for this: data havens;) escape from creditors; or financial regulation. Countries compete, too, by offering pro-monopoly policies, as we’ll see.

The end result is one set of light rules for wealthy individuals and large corporations that can afford to escape offshore, and another set of harder rules and higher taxes for lower-income people and more domestically focused small businesses, who can’t.

Brooke Harrington, a sociologist who took a wealth management qualification to study the super-rich, remembers a wealth manager telling her how she had once traveled with her CEO to meet a client outside Europe. At Zurich airport she realised she’d forgotten her passport, but the CEO told her not to worry: indeed, nobody checked their documents, either in Switzerland or at the other end. “The CEO was right,” the wealth manager said. “These people, our wealthiest clients, are above the law.” This deference to wealth, an aspect of Swiss ‘competitiveness,’ is a worldwide phenomenon. Should we be surprised at the recent outpourings of public rage?

The damage to democracy is unmeasurable. But what of the economic costs? Who wins, who loses?

It helps to separate this into two questions. First, what are the costs to the world as a whole, if lots of countries ‘compete’ in this way, offering tax cuts, subsidies, lax rules and other goodies to lure mobile capital to their shores, and stay ahead in a race to the bottom? Second, more selfishly: forget what happens to other countries – will it help my own country to ‘compete’ in this way?

The answer to the first is pretty widely recognised: this race to the bottom is a collective-action problem to be tackled with international collaboration and co-operation. From an OECD’s project to shore up international corporate tax, to the Basel rules on bank safety, such collaborative schemes abound. Yet they only get us so far – countries cheat, and it is also hard to mobilise domestic coalitions to support complex global projects.

The second question is more interesting. If we don’t offer subsidies to mobile capital, will the money run away to Geneva or Hong Kong, making us all poorer? If the answer is ‘yes,’ we are pretty doomed.

If the answer is ‘no,’ though, a world of possibility opens up.

The tax competitiveness puzzle

To clarify how this ‘competitiveness’ works we will first take a detour into the corporate income tax. It is a decent analogy for anti-monopoly policy because (for instance) monopoly-friendly legislation resembles a corporate tax cut: each entails a transfer of wealth from stakeholders in the relevant country to the shareholders of mostly large, profitable, foreign corporations. And instead of receiving public tax subsidies, monopolists use market power to impose private taxes on workers, citizens and consumers.

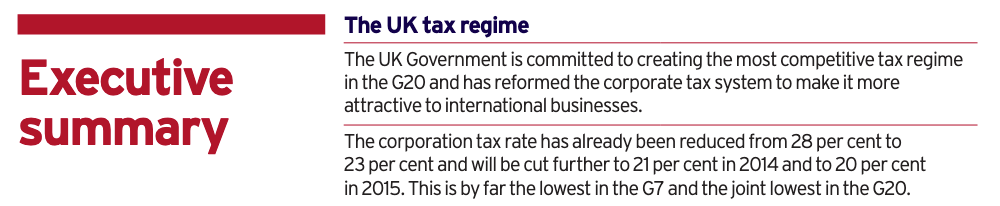

Take Britain, a poster child for the competitiveness agenda, as this official document in 2013 showed.

Did these ‘competitive’ tax cuts (which went down to 19 percent) subsequently make Britain better off? Was the trade-off — the tax costs, against extra investment, worth it?

The evidence is now in, and the answer is a clear ‘no.’ Indeed, the tax cuts may not have stimulated any useful net investment at all. Britain’s own Chancellor Rishi Sunak shocked many in his party when he admitted in March that:

“Over the last few years we haven’t seen that step change in the level of capital investment that businesses are doing as a result of those corporation tax reductions.”

Why did the corporate tax cuts fail Britain? For several reasons, in fact.

First, a corporate tax is not a cost to an economy, but more like a transfer within it, from corporations to the public. The nine percentage point cut in the corporate tax rate from 2013-2020 now costs the UK over £30bn ($42bn) in lost taxes a year, on official UK estimates, enough to double UK public spending on research and development, with billions left over.

Second, tax is usually a low priority for firms as they decide where to invest. Survey after survey finds that good investors seek good infrastructure, the rule of law, healthy and educated workforces, and access to vibrant local markets – most of which need tax anyway.

Mostly, investors decide where they want to invest, long before they consider the tax rate. For example, Amazon recently encouraged a bidding war among U.S. states seeking to attract its second headquarters, suggesting that the biggest subsidy package would win. Veteran Amazon-watcher Scott Galloway saw through the spin:

“Over the last few years we haven’t seen that step change in the level of capital investment that businesses are doing as a result of those corporation tax reductions.”

He predicted that whatever other states offered, the HQ would end up in the orbit of “the metro area of New York or DC” – which is just what happened.

Paul O’Neill, former boss of Alcoa (and US Treasury Secretary under George W. Bush), gave a business perspective:

“As a businessman I never made an investment decision based on the tax code… if you are giving money away I will take it. If you want to give me inducements for something I am going to do anyway, I will take it. But good business people do not do things because of inducements.”

As we saw in a recent edition of The Counterbalance, large ‘superstar’ corporations have big markups and make the big profits, so pay the most corporate income tax. So ‘competitive’ corporate tax cuts benefit large, dominant firms the most. (That’s another glimpse of the pro-monopoly bias of the competitiveness agenda.)

Furthermore, corporate tax cuts also flow mostly to shareholders, typically overseas (for example, over 55 percent of UK-quoted shares are owned overseas.) So such tax cuts both leak wealth upwards, from small businesses and individuals to large corporations: but also outwards, overseas. From a national self-interest perspective, that’s bad.

And the competitiveness agenda — which implies hanging up a sign in the global marketplace, saying ‘Come Exploit Me’ — will tend to attract predatory players, while the more productive ones would come anyway. As a recent book explained:

“Countries need investment that’s embedded in the local economy, bringing jobs, skills and long-term engagement, where managers send their kids to local schools and the business supports an ecosystem of local supply chains. This is the golden stuff, and if it’s nicely embedded, then a whiff of tax [or public-interest regulation] won’t scare it away. If an investor is more sensitive to tax, then almost by definition it has shallower roots; tax will tend to frighten away the less useful, more predatory stuff.”

Tax, or robust public-interest competition policy, preserves the healthy and deters the harmful.

Worse still, the race to the bottom means that any country that tries to get ahead in this race may soon be back to square one relative to other states – but with a greater commitment to subsidise investors. And that downwards race does not stop at zero, as Amazon’s Hunger Games competition shows: the subsidies just keep piling up.

What goes for tax, goes for finance

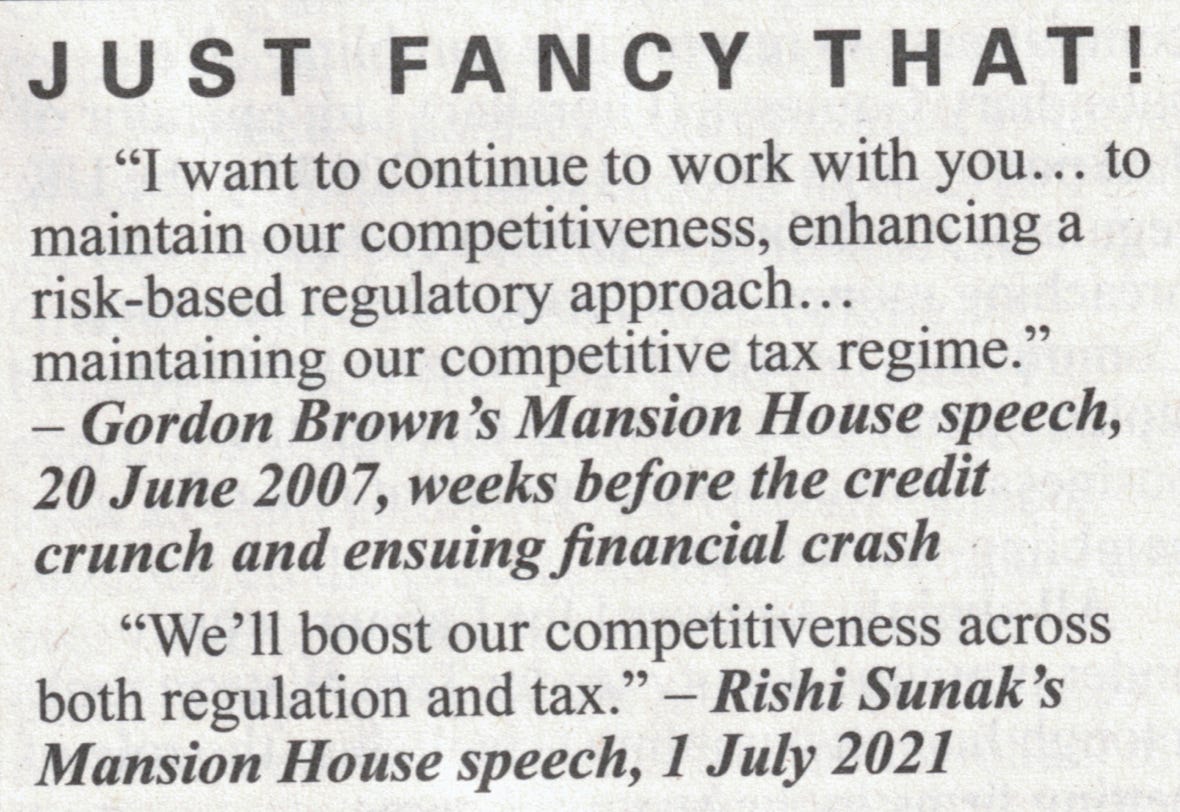

We can generalise these tax lessons to other areas. For instance, see this from Britain’s satirical / investigative magazine Private Eye:

In the London Loophole chapter of my book The Finance Curse, I show how this ‘competition’ between financial centres, principally between New York and London, was a core driver of the global financial crisis. Britain handed out vast regulatory goodies to attract risky financiers – and in the end they kept their winnings, while the British people paid the costs.

After the crisis the word ‘competitiveness’ was mostly expunged from the British policy lexicon, but it never disappeared, just went underground. Sunak’s July speech, with plans to “sharpen our competitive advantage” in finance, was just one post-Brexit sign of a wider comeback, across many sectors.

So what is “competitive” competition policy?

Since the 1990s, many politicians fell under the spell of “Third Way” economic policies espoused by US President Bill Clinton and UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. They embraced the Competitiveness Agenda, including an idea that, as Clinton put it, each nation is “like a big corporation competing in the global marketplace.” European policy makers, who had once fretted about how monopolisation had spurred Nazism in Germany (watch out for a future edition of The Counterbalance on this,) slowly lost their aversion to corporate size, and instead imbibed a new story. The new ideas, which emerged in Chicago from the 1970s, ignored questions of power, the structure of markets, or the public interest, and instead narrowed the focus down to the question of whether consumers were getting a good deal. Mergers and bigness were efficient: if workers or the environment or even the tax authorities could be exploited and the ‘savings’ channelled into lower prices, then all was good.

This Chicago agenda was also seen as ‘competitive’ its ‘exploit me’ message would, it was hoped, attract capital and investment. “This merger tsunami is a good sign [and supports] “Europe’s competitiveness,” gushed Europe’s Competition Commissioner Neelie Kroes in 2007. (Not much has improved since: European authorities almost never block big mergers.)

These ideas have spread further afield. As a south Asian competition expert, who wished to remain anonymous, told us:

“a lot of countries are recipients not originators of competition models . . the economic imagination has been global, not domestic . . the idea was, to put in this competition law, and it will attract foreign direct investment (FDI).”

Similarly, a South African competition expert told us:

“FDI has been the main focus why the public interest should not be in competition law.”

(Though as we recently noted, South Africa has started to go against the grain, blocking a Burger King merger on public interest grounds.)

The perils of national champions

Another strand of this way of thinking involves “national champions” (more on them, in future editions of The Counterbalance.) From British politicians looking for “ways we can build trillion-dollar tech companies” to French presidents mulling how to build globe-striding French energy giants, the idea is that countries should soft-pedal on reining in their dominant firms, so that they can become powerful enough to go head to head with (for instance) Americans or Chinese firms in the global marketplace, and that this, in turn, will benefit the nation.

This is an old idea, sarcastically skewered in 1904 by the Norwegian-American economist Thorstein Veblen, (hat tip: Matthew Watson)

“In this international competition the machinery and policy of the state are in a peculiar degree drawn into the service of the larger business interests; so that, both in commerce and industrial enterprise, the business men of one nation are pitted against those of another and swing the forces of the state, legislative, diplomatic, and military, against one another in the strategic game of pecuniary advantage.

. . .

the common man pays the cost and swells with pride.”

Or, as the FT writer Rana Foroohar put it more recently:

“It is easier to capitulate to populism by supporting national champions than it is to craft and pass smart national growth strategies.

The national champions argument boils down to an idea that we must boost our ‘competitiveness’ by sabotaging healthy market competition, so as to let ‘our champions’ grow powerful. The evident confusion here — improve competitiveness by reducing competition — underlines the idea’s intellectual bankruptcy, and indeed that of the entire competitiveness agenda. (Has Facebook’s existence really benefited the United States? The damage it has inflicted is incalculable.)

There has to be a better way. Fortunately, there is – and it is starting to catch on.

From downgrading to upgrading

One can imagine two main routes to something you might call ‘national competitiveness.’ One is the low-tax, low-regulation, low-enforcement, pro-monopoly race to the bottom that I’ve described: in a word, ‘downgrading.’ We’ve tried this since the 1980s, and the results are clear: the massacre of small businesses, soaring inequality, environmental harm, security risks, and popular fury.

The economist Paul Krugman warned about this agenda in 1994, in a now-famous article entitled “Competitiveness: a Dangerous Obsession.” In it, he wrote:

“The growing obsession in most advanced nations with international competitiveness should be seen, not as a well-founded concern, but as a view held in the face of overwhelming contrary evidence. And yet it is a view that people very much want to hold.”

A more sensible alternative approach could be called “upgrading.” Here, governments invest in good things that businesses need – infrastructure, education and health, research and development, and so on. Regulation or tax policy does not seek to attract FDI through giving it an easy ride, but instead shepherds businesses to compete in markets regulated in the public interest, liberated from the monopolising predations of dominant giants. Instead of chasing dominant ‘national champions’ we pursue ideas promoted over a century ago by the U.S. Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis: a distributed infrastructure of supply, with many competing players all down the supply chains, each regulated in a level playing field and the public interest.

Take, for example, Britain’s music industry. The “downgrading” strategy favours letting streaming services and other music behemoths exploit British musicians, in the hope that the giants will invest more in Britain. But, as campaigner Tom Gray put it:

“The British political class have been convinced by the major labels – let’s be clear: foreign-based multinational companies – that they are the great driver of British music. When in fact British musicians are the driver of British music.”

‘Upgrading’ to stop the giants preying on musicians would unleash an explosion of creativity and, yes, an export surge of wonderful British music, spreading good vibrations globally.

There’s no need think about upgrading in terms of ‘competitiveness’ relative to other nations. If Germany improves its education, upgrades its financial regulations to protect its taxpayers better from risky speculation, or invests in vaccine research and development, French people won’t lose out. On the contrary, these improvements will make French employees and taxpayers more productive and richer, as better-off German consumers buy more French goods. Better vaccines help everyone. Competitiveness, Krugman said, often turns out to be “a funny way of saying ‘productivity’ ” – not relative to other nations, just on its own.

The good news here is that we don’t need to bow down to mobile capital and ‘downgrade to compete’ – we can just do what our voters want. There is no trade-off: we will have both a stronger democracy, and greater prosperity.

The other good news is that – while the agenda may be making a comeback in the U.K. after Brexit, the Biden Administration in the U.S. is deliberately stepping away from it. In April, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made the clearest policy statement repudiating the agenda, favouring the upgrading route over the downgrading.

“The US will compete on our ability to produce talented workers, cutting edge research & state-of-the-art infrastructure, not on whether we have lower tax rates than Bermuda or Switzerland. It’s a self-defeating competition, and neither President Biden nor I are interested in participating in it anymore.”

This attitude goes far beyond tax too. The appointments of Lina Khan and Jonathan Kanter to head the U.S.’ two main antitrust agencies, respectively the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust division, signal a potentially dramatic policy shift in favour of small businesses and ordinary folk, at the expense of dominant (and mobile) multinationals. They represent a stunningly successful anti-monopoly movement in the United States (sometimes known as the New Brandeis Movement) which has heavily influenced our thinking. A presidential Executive Order has backed this up recently with a wide set of curbs on monopoly power. This is a ground-breaking, world-changing shift in approach that potentially leaves other countries far behind.

This, at last, is the sort of global race where it’s good to lead the pack. Who will follow?

Related articles

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

The People vs Microsoft: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Can the UN succeed? Top questions about our State of Tax Justice report

Switzerland’s tax referendum is a choice between tax havenry and more tax havenry

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #66: الضريبة الموحدة على الشركات والفرص الضائعة