Andres Knobel ■ Another EU court case is weaponising human rights against transparency and tax justice

After the infamous ruling of November 2022 by the European Court of Justice that rolled back public access to beneficial ownership information, another case now pending in the European Court of Justice could deal an even worse blow to the fight against transparency and tax justice. Once again an individualistic concept of human rights, particularly the right to privacy, is being weaponised, this time to protect lawyers who enable illicit financial flows when they create secrecy vehicles such as companies and trusts.

Introduction

The EU is still trying to recover from the November 2022 strike against transparency that resulted in many EU countries, starting with Luxembourg, closing their public beneficial ownership registries. We welcome the approval in 2024 of the EU AML Package with provisions for legitimate interest access by civil society organisations, journalists, academia as well as foreign authorities is welcome, though it’s a poor substitute for public access.

Now, a new EU case concerning lawyer’s professional confidentiality could deal an even worse blow to the fight for transparency and tax justice. The new case arose from a request by Spain’s tax administration to Luxembourg for information about a law firm’s services to a Spanish company. The exchange of information request was based on Directive 2011/16/EU on Administrative Cooperation in the Field of Taxation. The Spanish authorities were specifically interested in details of the acquisition by an investment group of a Spanish company and shares in another entity. The law firm refused to provide the information based on their legal professional privilege (LPP), which protects a lawyer’s communications with their client. Luxembourg’s tax administration imposed a fine on the law firm for failing to comply with the provision of information request. The law firm, with the support of the Luxembourg lawyers’ Bar Association, challenged the decision before the Luxembourg national court. The Luxembourg administrative court dismissed the action, so the law firm and the Bar lodged an appeal with the Higher Administrative Court. This Court decided to stay the proceedings and referred questions to the European Court of Justice regarding the right to privacy vis a vis legal advice provided by lawyers on matters of company law.

Before the European Court of Justice delivers its ruling, the Advocate General issues a non-binding legal opinion. On 30 May 2024, the Advocate General to the European Court of Justice Juliane Kokott published her legal opinion on the case. She agreed with the law firm. In essence, the Advocate General considered that lawyers should enjoy legal professional privilege (aka a right to secrecy) not just when they are defending a client in court, but also when they are hired by the wealthy to create companies and other investment structures.

This legal opinion will bolster the (ab)use of this special confidentiality of lawyers to protect criminals, high net worth individuals and multinational companies from scrutiny by authorities when creating secretive structures.

This blog post has three parts. First, it looks at this case within the context of a campaign to promote human rights from an individual perspective (eg privacy, data protection) against human rights from a wider-society perspective (eg health, education, housing, a clean environment, rule of law). Second, the blog post offers an analysis of the legal opinion itself in light of the secrecy risks that it creates. Thirdly, it finishes with a long-overdue proposal to establish a clear limit to lawyers’ legal professional privilege when it comes to legal advice unrelated to a current trial.

1. Individual rights versus the public interest

There appears to be a campaign to argue for the human rights of rich and powerful people and corporations against the public’s right to transparency and tax justice. This new legal case on lawyers’ confidentiality is another attempt in the ongoing campaign by law firms and data protection authorities in Europe and elsewhere to weaponise privacy, and its corollary data protection, against public-interest transparency advances. So far, the campaign has covered:

- upon request exchanges of information between tax authorities (the new legal opinion)

- automatic exchange of bank account information (eg in Belgium and the UK),

- public beneficial ownership registries (eg in Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the US),

- mandatory disclosure rules to disclose aggressive tax planning and schemes to circumvent automatic exchange of information or hide beneficial owners (eg in Argentina, Belgium and Ecuador).

In parallel to this campaign to use courts to strike down transparency advances, there is academic work to bolster individual’s rights over public interest. For instance, Advocate General Kokott co-authored a paper published in 2021 on Taxpayers’ Rights, where she and fellow authors detailed their approach to the human rights of taxpayers. While they accepted that there is a ‘collective right’ to tax justice, and even that it is ‘fundamental’, their view was that ‘the protection of fundamental collective interests must not go so far as to infringe individual fundamental rights’. From this perspective, ‘the international fight against tax avoidance, evasion, and fraud’ is a matter for tax authorities, governments and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

This idea of human rights from an individual perspective against human rights from a wider societal perspective has four major flaws.

First, it assumes that the collective rights of the public are currently adequately protected by governments and authorities. However, tax and law enforcement authorities tend to be understaffed, lack appropriate budgets and technological resources, and in some worse cases even suffer from political pressure or corruption. To make matters worse, incentives to protect the enforcing of laws and rights in favour of society as a whole are much weaker than the incentives for powerful individuals to benefit themselves. In other words, it’s much easier for a rich tax evader to hire lawyers to protect their rights in court than it is to mobilise the many individuals whose human rights to health, education and a decent life depend on fair and effective taxation, the fight against money laundering and corruption, etc. This is the classic challenge of any collective action to overcome unjust structures.

Secondly, it results in a view of human rights that protects wealth and advantage over the basic needs of all individual human beings because it considers civil and political rights as more important than social, economic and cultural rights. This perspective sees all people, including ‘legal persons’ as equal, with equal rights. The consequence is that human rights legislation potentially protects companies, money and property to the same extent, or more than, basic human needs for health, housing, etc. However, it is essential to recognise that social and economic rights of all individuals are just as important as civil and political rights. Critical to this seeming conflict between individual rights versus collective rights is the recognition of States as key duty bearers for human rights of all citizens, especially when considering the needs of vulnerable people. The Principles for Human Rights in Fiscal Policy sets out how “states must be free from undue influence from corporations or those working to further their fiscal interests to the detriment of human rights realization”.

Thirdly, it is based on perceptions that tax enforcement, transparency or equality before the law only remotely and indirectly affect human rights, including not just health, education and housing but also the right to life or freedom. As we explain in our paper “Why beneficial ownership registries aren’t working”, it appears that people are more willing to allow for intrusive measures (eg airport checks on passengers’ luggage and personal items) when the danger to the right of life is more direct and obvious (eg stopping a terrorist attack). However, corruption, money laundering or tax abuse are not perceived as a threat to life and other basic human rights, and courts tend to be used to assert legal protections for the wealthy and powerful to use secrecy over transparency measures such as public access to beneficial ownership information or now, establishing limits against legal professional privilege. Nevertheless, the cases of fires and explosions in Argentina’s concert hall, the Bangladesh factory or Lebanon’s port show that corruption also results in the loss of life, facilitated by secretive legal vehicles, a view firmly established among global institutions such as the World Bank for over a decade.

Fourthly, no right is absolute and particular rights should not be exploited to undermine other rights. Just as the interest to board an airplane without passing a security check should not be understood as an interest to be protected by the right to free movement, neither should the refusal to provide information to authorities (or to publicly disclose beneficial ownership information) be understood as something that should be protected by the right to privacy.

The individual interest in secrecy by the rich and by powerful corporations must also be balanced against the individual and collective rights of others. Ensuring secrecy in favour of law firms and companies also affects both “individual” civil and political rights (e.g. the right to access information), and the “individual or collective” dimensions of economic and social rights. For instance, rights such as the right to health or education have an individual component as well because they protect individual claims before the law – having individual access to healthcare or to primary education).

Even if the Court found that the law firm has a legitimate defence in claiming protection under the law to refuse to divulge information, no right should be considered absolute, and the tools of balancing or harmonising conflicting rights should be used appropriately. That means in our view that the requirement to publish certain types of information, such as beneficial ownership information or a simple request for information by an authority in this case, is not a disproportionate restriction of the right to privacy because it protects other rights that would be at risk if secrecy were maintained in these cases.

In conclusion, academic work and lawsuits are pushing for a view of human rights that protects the rights to privacy and private property of companies and other legal structures. The problem with this perspective is that a blanket wall that protects secrecy around the ‘right to set up a corporate investment structure’ may end up aiding activities that are clearly against the public good, such as corruption, money laundering, tax evasion and avoidance. Legal professional privilege would make it impossible to distinguish between what is lawful and unlawful, as everything a lawyer advised on would become confidential.

2. An analysis of the legal opinion

The Advocate General’s Opinion gives an extraordinarily wide interpretation of the right to privacy under the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU which would have potentially enormous consequences for tax enforcement and cooperation in the EU. Three main points can be singled out:

2.1 Protection of privacy and family life should not extend to enabling illicit financial flows.

Article 7 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union states that ‘Everyone has the right to respect for his or her private and family life, home and communications’. The Advocate General argues that ‘legal persons too can rely on the right to respect for private life’. This legal opinion proposes to go well beyond a previous decision of the Court which accepted that the individual’s right to protection of their personal data extended to when their name appears in that of a company. The legal opinion states:

It is true that the Court has held that ‘legal persons can claim the protection of Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter … only in so far as the official title of the legal person identifies one or more natural persons’. However, that distinction concerns only the processing of personal data under Article 8 of the Charter. Conversely, legal persons too can rely on the right to respect for private life that is protected by Article 7 of the Charter. This must be particularly true of the protection of communications, likewise protected by Article 7 of the Charter, in particular LPP…. The object of protection, after all, is the relationship of trust between lawyers and their clients. Such a relationship also exists between the lawyers brought together within a company, on the one hand, and their clients or their clients’ agents, on the other. The legal form within which the lawyer or the client acts is immaterial in this regard.

Yes, you read that right. According to the Advocate General’s legal opinion, the right to ‘respect for private and family life, home and communications’ applies not just to real people, but also to companies and law firms, and hence to communications between them!

Contrary to the expansion of the right to privacy to protect the secrecy of law firms and companies, one could consider the report by the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression in the aftermath of the European Court of Justice’s November 2022 ruling on beneficial ownership registries. The Special Rapporteur considered the balance between conflicting interests in terms of the right to privacy:

“The relationship between data protection, the right to privacy and the right to information is complex and requires a careful balancing of interests. That in turn requires that laws and policies clearly define, on the one hand, the personal information that is protected legitimately under the right to privacy and, on the other, the public interest justifying disclosure. Under such a test, even if the information is determined to be personal and its release would infringe privacy, it may be disclosed if the public interest in release is more important than the privacy interest.”

(A/HRC/53/25: Sustainable development and freedom of expression: why voice matters – Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression)

Additionally, the idea of companies and law firms having equal rights to individuals and the general public is in direct conflict with their responsibilities as outlined in the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Business enterprises have a responsibility to respect human rights, including not only infringing on others’ rights but also addressing adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved. Allowing businesses to enjoy secrecy around matters that could cause the widespread infringement of human rights for large groups of people through tax abuse, money laundering or corruption would be antithetical to the very idea of human rights principles.

2.2 Lawyers are not necessarily always interested in the rule of law

The Advocate General argues that legal professional privilege is a fundamental right for a just society:

After all, lawyers are not only representatives of their clients’ interests but also independent collaborators in the interests of justice. Consequently, LPP [legal professional privilege] protects not only the individual interests of lawyers and their clients but also the public interest in justice being administered in such a way as to fulfil the requirements of the rule of law. Thus, the special protection afforded by LPP [legal professional privilege] is also an expression of the principle of the rule of law on which the European Union is founded…

The legal opinion argues that legal professional privilege extends to any legal advice, not only from a lawyer (para. 61), and protects not only the individuals but the general public (para. 58). This means that any powers given to public authorities to ensure due compliance with the law, including tax law, must be ‘balanced’ against the right of those devising abusive schemes to keep their advice confidential. In the words of Advocate General Kokott: ‘In the light of the importance of LPP [Legal Professional Privilege], after all, fact-finding enquiries cannot be conducted at any price’ (para. 59).

If authorities are unable to obtain information due to legal professional privilege, how can they verify compliance with the law, and hence that the rule of law actually is being upheld? It appears as if the Advocate General assumes that all professionals giving legal advice always act in the interests of justice; not only are they never corrupt, but they never try to find loopholes and weaknesses in the legal rules in the interests of their clients, which they seek to conceal from regulatory authorities. Allowing them to keep their schemes secret would blindfold authorities, which are already so under-resourced that they have an almost impossible task in trying to stop tax evasion and avoidance.

It is not clear how the Advocate General can assert this in light of the evidence of the involvement of professionals such as lawyers and accountants in creating offshore companies facilitating illicit financial flows, especially as revealed by major leaks by whistleblowers, notably the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers.

Contrary to the view that lawyers always stay within the law and promote the rule of law, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which sets global anti-money laundering standards, has been warning about the role of legal professionals in money laundering for more than a decade:

…the use of legal professionals to provide a veneer of respectability to the client’s activity, and access to the legal professional’s client account, is attractive to criminals. There is also a perception among criminals that legal professional privilege/professional secrecy will delay, obstruct or prevent investigation or prosecution by authorities if they utilise the services of a legal professional.

(FATF 2013 report on “Vulnerabilities of Legal Professionals”, page 23)

According to the Financial Action Task Force, the situation had not changed much six years later:

Criminals may also seek out legal professionals (over other non-legal professions) to perform the services listed in R.22 with the specific criminal intent of concealing their activities and identity from authorities through professional privilege/secrecy protections.

(FATF 2019 “Guidance for a risk-based approach for legal professionals”, page 23).

The Financial Action Task Force also explains that the mere possibility of invoking legal professional confidentiality directly affects investigations and can let lawyers off the hook:

… differing interpretations by legal professionals and law enforcement has at times provided a disincentive for law enforcement to take action against legal professionals suspected of being complicit in or wilfully blind to ML/TF [money laundering/terrorism financing] activity…

Claims of legal professional privilege or professional secrecy could impede and delay the criminal investigation… In many instances this means that the claim of legal professional privilege or professional secrecy will need to be resolved by a court, which can delay the investigation process for a substantial period of time. As time is a critical factor in pursuing the proceeds of crime, this may influence the decision of investigators of whether to investigate the possible involvement of the legal professional or to seek evidence of their client’s activities from alternative sources.

(FATF 2013 report on “Vulnerabilities of Legal Professionals”, pages 6, 31-32)

Using human rights to undermine legitimate inquiries by public authorities authorised by democratically approved laws is a travesty of the rule of law.

2.3 Protection of human rights should not be used as a green light to create secretive companies and investment structures

The most dangerous part of the legal opinion is the broad confidentiality protection for lawyers’ involvement in the formation of companies and investment structures, which is one of the main ways to create complex secrecy structures which may engage in illicit financial flows.

The Advocate General writes:

Since it is therefore impossible to draw distinctions between the various fields of law – as Luxembourg has done in this case – when determining the scope of the protection afforded by LPP, that protection extends to legal advice in the field of company and tax law, too. In particular, advice on the establishment of a corporate investment structure such as that at issue here also falls within the scope of the protection afforded by LPP.

This extension poses grave dangers, considering that the Financial Action Task Force has identified several cases of legal professionals assisting or directly engaging in money laundering through the creation of companies.

According to the Financial Action Task Force report on “Vulnerabilities of Legal Professionals”:

Inherently these activities pose ML/TF [money laundering/terrorism financing] risk and when clients seek to misuse the legal professional’s services in these areas, even law-abiding legal professionals may be vulnerable. The methods are: … creation of trusts and companies; management of trusts and companies; …; and setting up and managing charities. (page 4).

Annex 5 to the same Financial Action Task Force 2013 report lists 126 examples of real cases where legal professionals were involved in money laundering or financing of terrorism. Out of these, 45 cases included the method of a legal professional obscuring ownership through the creation of companies, trusts, use of bearer shares or acting as trustees. For instance, “Case 59” involved “legal professional creates complicated foreign structures and transfers funds through client account while claiming privilege would prevent discovery.”

Recommendation 16 of the 2019 UNODC Global Expert Group meeting on Corruption Involving Vast Quantities of Assets also proposed to exclude legal professional privilege when lawyers act as formation agents of legal persons:

To prevent the facilitation of corrupt activities, legal privilege or professional secrecy should protect only activities that are specific to the legal profession, such as ascertaining the legal position of a client, providing legal advice, or representing a client in legal proceedings. These protections should not extend to activities performed by a legal professional that are purely financial or administrative in nature, such as handling client funds, acting as a nominee director or shareholder on behalf of a client, or acting as a formation agent of legal persons.

3. Establishing limits on professional confidentiality

Although the weaponisation of privacy has hit mostly in the European Court of Justice, international standards (including those set by the Financial Action Task Force or the Global Forum) also share some blame for allowing professional confidentiality to become a barrier to transparency and protection of fundamental human rights principles.

Already, the Financial Action Task Force’s Recommendation 23 allows lawyers not to file suspicious transaction reports, based on professional confidentiality. The actual text of Recommendation 23 states that lawyers, notaries, accountants and other legal professionals are required to report suspicious transactions when, on behalf of or for a client, they engage in, among others, the organisation of contributions for the creation, operation or management of companies or the creation, operation or management of legal persons or arrangements, and buying and selling of business entities. However, the Interpretative Note then states that legal professional privilege can protect lawyers against filing information:

Lawyers, notaries, other independent legal professionals, and accountants acting as independent legal professionals, are not required to report suspicious transactions if the relevant information was obtained in circumstances where they are subject to professional secrecy or legal professional privilege.

It is for each country to determine the matters that would fall under legal professional privilege or professional secrecy. This would normally cover information lawyers, notaries or other independent legal professionals receive from or obtain through one of their clients: (a) in the course of ascertaining the legal position of their client, or (b) in performing their task of defending or representing that client in, or concerning judicial, administrative, arbitration or mediation proceedings. (emphasis added).

Likewise, the Global Forum on Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes’ Standard under Section C.4.1 allows countries not to exchange information when it would violate attorney client privilege:

Requested jurisdictions should not be obliged to provide information which would disclose any trade, business, industrial, commercial or professional secret or information which is the subject of attorney client privilege or information the disclosure of which would be contrary to public policy.

Where to draw the line between lawyers’ confidentiality and requiring them to provide information to authorities?

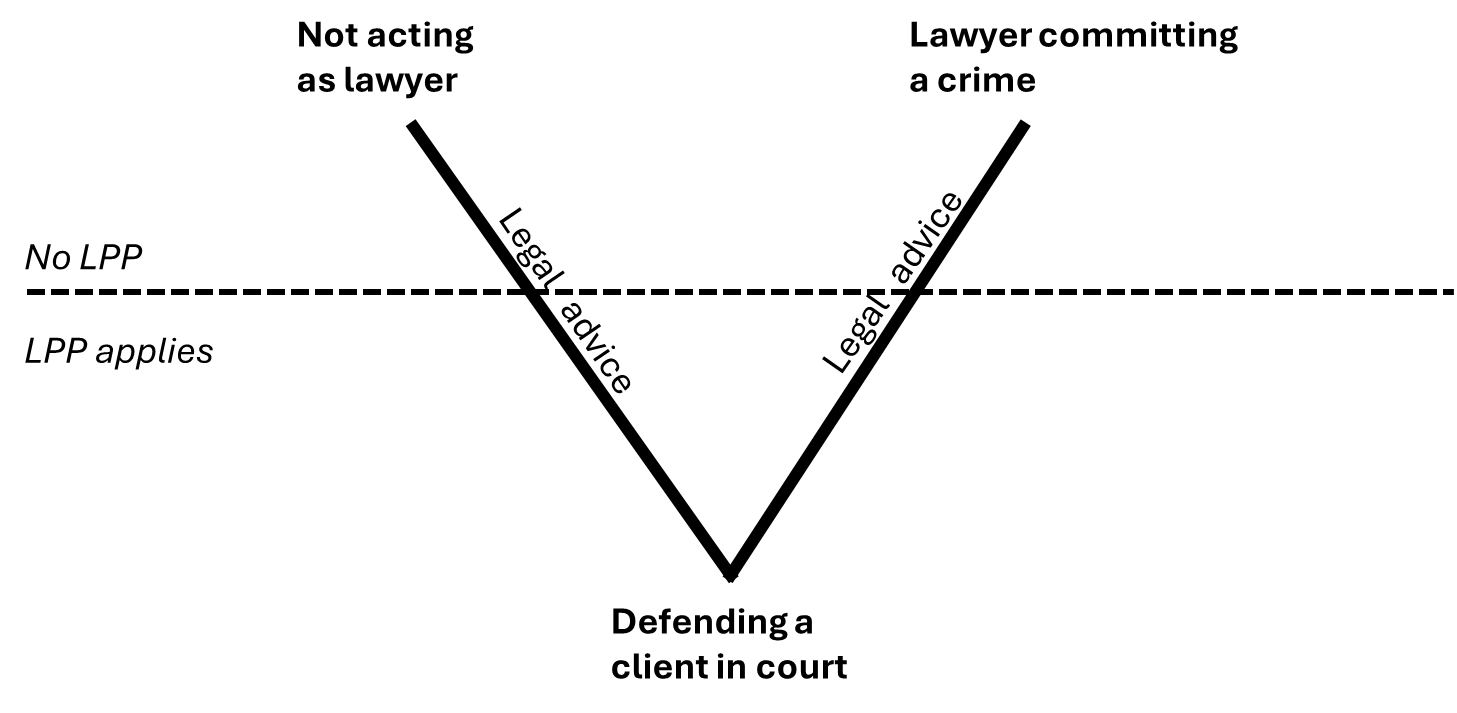

Legal professional privilege can be thought of as a spectrum following the letter “V”. The three extremes are easy. The two top vertices are clearly beyond legal professional privilege: one would include a lawyer who isn’t acting as one, but rather as a salesperson or manager. The other would refer to a case where the lawyer is acting illegally and committing a crime (eg engaging in money laundering). On the other hand, the bottom vertex involves a lawyer defending a client in court in the context of a trial, a situation that in most (if not all) countries would ensure the protection of legal professional privilege. The question is where to draw the line for legal advice.

Source: elaborated by author

In relation to the first top vertex, the Advocate General states that there would be no legal professional privilege when a lawyer acts in a commercial way as part of a management consultancy firm:

…that protection covers only information shared in the context of an activity involving the provision of legal advice as part of a specific instruction. In addition, however, lawyers may engage in commercial practice too, as part of a management consultancy firm, for example. To the extent that they do, lawyers do not practise as independent collaborators in the interests of justice. By extension, therefore, information obtained in that context does not require the same protection as information obtained as part of the provision of legal advice.

As for the other top vertex, even the International Bar Association’s report “Statement in Defence of the Principle of Lawyer-Client Confidentiality” affirms that confidentiality ends when the lawyer is assisting, aiding or abetting unlawful conduct:

The protection provided by lawyer-client confidentiality does not apply when a lawyer is knowingly assisting, aiding or abetting the unlawful conduct of his or her clients. In such circumstances, the lawyer would be committing a criminal offence in most jurisdictions (page17).

Drawing the line for “legal advice” should depend on the risk of illicit financial flows

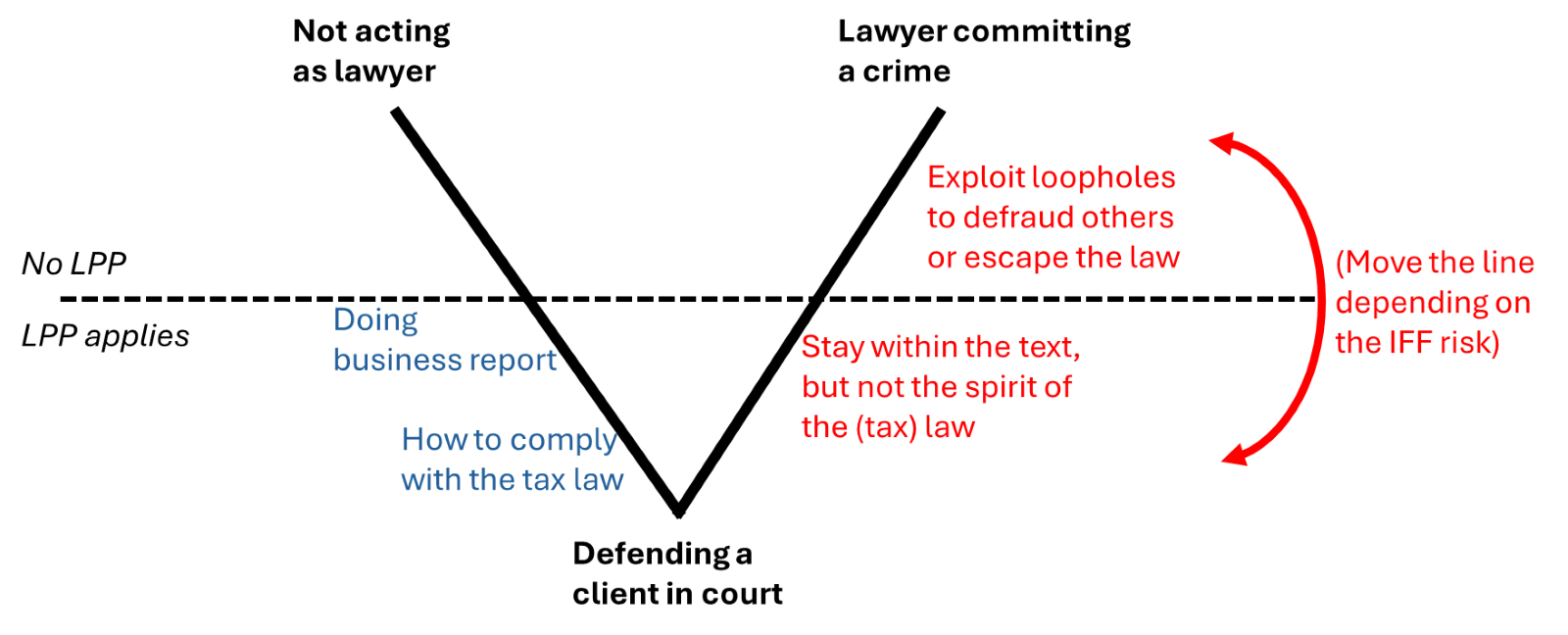

The main question is what happens when a client seeks legal advice from a lawyer before any legal proceedings apply. In this case, the conduct, either legal or illegal, is merely being planned or considered. We propose that the line should be drawn depending on the risks of illicit financial flows.

If the legal advice is about how to interpret the law or how to comply with the law exclusively for commercial purposes, this legal opinion would likely be covered by legal professional privilege, but this shouldn’t create any risk of illicit financial flows. For instance, we are talking about a “doing business report” where a lawyer explains to a foreign investor what types of companies there are in the country, or what would be the most suitable type of company or investment, exclusively based on the commercial (non-tax) purpose of the client.

If the legal advice sought from the lawyer is to identify all the loopholes in the law to escape the law, eg how to set up a bank account to circumvent automatic exchange of bank account information, how to set up a discretionary trust to prevent asset recovery or to exploit secrecy or asset protection against authorities or third parties in any other way, then this should not be subject to confidentiality protection because of the high risk of illicit financial flows.

This finally brings us to the issue of tax advice. If a client asks a lawyer for tax advice to stay within the literal meaning of the law and within the spirit of the law, this could also enjoy the protection of professional confidentiality because it wouldn’t be creating illicit financial flows risks. For instance, we refer to a case where a tax lawyer explains that tax incentives may be legally obtained by investing X percent in green energy, or by financing through debt rather than equity because the law allows for special interest deductions. In other words, the lawyer would merely be explaining what the law is trying to say. Tax authorities should have no problem with that.

However, a lawyer who offers tax advice to stay within the literal meaning of the law, but against the spirit of the law or against a likely interpretation of the law by the tax administration, should be considered unlawful and should therefore not enjoy legal confidentiality because of the tax abuse risks.

The next figure illustrates where the line could be drawn depending on the low/no risk of illicit financial flows (in blue) versus the high risk of illicit financial flows (in red):

Source: elaborated by author

The legal opinion makes it impossible to draw the line in practice, making everything a lawyer touches privileged information

The approach adopted by Advocate General Kokott creates a Catch-22. It makes it difficult to apply the distinction between being covered or not by legal professional privilege, even in a situation where a lawyer is acting illegally.

The whole point of giving authorities fighting illicit financial flows, including a tax administration, the right to obtain information is to enable it to determine if any unlawful activity is taking place. To allow a refusal unless the lawyer knows that unlawful conduct is involved assumes that only the client may be acting in a potentially unlawful way. If a lawyer has indeed knowingly advised an unlawful act, they would be unlikely to divulge the information to the authority. Lawyers who engage in money laundering have promoted their special confidentiality rights as a way to avoid authorities. Likewise, lawyers engaging in “tax mining” who devise tax dodging schemes generally claim that they think the schemes may be lawful, but they do not guarantee this. Unless authorities can obtain information about the scheme, they have no way to even look at, and challenge the lawyer’s advice.

This would give free rein for enablers of all kinds to devise and propose schemes for corrupt purposes such as money laundering, tax evasion and avoidance, leaving authorities powerless to challenge them.

A committee to decide on each case

While most people would agree that there should be no confidentiality protection when a lawyer acts in their personal capacity or when they are evidently offering to breach the law, there is a need for international standards and for countries to establish rules when the case isn’t as obvious. This would include cases where a client seeks legal advice on:

- how to circumvent laws (eg how to avoid the automatic exchange system, how to hide the beneficial owner or evade taxes), or

- how to stay within the text of the law, but going against the spirit of the law, or going against a likely interpretation or view by the tax authorities.

At the same time, it should not be up to a lawyer to qualify their legal advice, because they would always claim to be protected by confidentiality. It would thus make sense, that whenever authorities request information from a lawyer and they refuse to provide it, invoking legal professional privilege, then the documents should be sent to a special (and speedy) committee. This committee should include members of the bar of association, competent authorities and judges to determine which of the documents, if any, can be shared with authorities. The committee could also determine if any information should be redacted, provided the committee can prove that no unlawful or abusive conduct is being enabled by the lawyer.

Conclusion

The European Court of Justice is set to again deliver a ruling that could have a huge impact on transparency, exchange of information and the fight against illicit financial flows, especially if it considers that any case of company formation by lawyers would be subject to legal professional privilege.

In our view the Court should firmly reject this attempt by the Advocate General to undermine the powers of authorities, including tax administrations, to obtain information about business arrangements. Competent authorities are themselves already under strong obligations to protect the confidentiality of taxpayers’ information and personal data. This applies also to information they share and obtain through legal procedures now established for mutual assistance, such as the EU Directive. We fail to see how the rule of law is in any way affected by giving them the powers necessary to obtain information they need to enforce the law.

The Court should also draw a firm line to reject the specious arguments that would extend the human right to privacy and family life and communications to protect companies and business arrangements. This would be a distortion of the concept and purpose of human rights protection.

Related articles

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The bitter taste of tax dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss swindle’

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research