Andres Knobel ■ New report on how to fix beneficial ownership frameworks, so they actually work

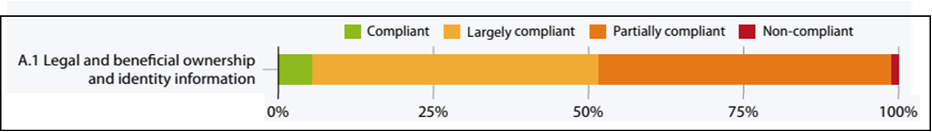

Close to 100 countries have approved beneficial ownership registration frameworks. Many of these countries will likely have to upgrade them after the recent reforms of the Financial Action Task Force recommendations 24 and 25 on beneficial ownership transparency for legal persons and trusts. And if not based on the reforms, then based on the pretty bad ratings given them by the Global Forum 2023 Annual Report:

EU countries, which are still reeling from the European Court of Justice’s ruling against public access, continue to negotiate changes to their beneficial ownership registries as part of the so-called “AML Package”. In this context, the Tax Justice Network has published a new report “Why beneficial ownership frameworks aren’t working – and what to do about it”.

Why this report?

We agree with secrecy supporters that beneficial ownership registries haven’t solved the issue of illicit financial flows. Tax evasion, money laundering and corruption keep flourishing unabated. However, this is not a reason to throw loophole-ridden beneficial ownership registries out with the proverbial bathwater. On the contrary, it just adds more urgency to get them right.

There are many things to fix. Applying verification and expanding access to all stakeholders (ie public access) so that beneficial ownership can serve multiple uses are obvious first steps. But our latest report deals more with the fundamentals: getting the law right to begin with. In this regard, complying with the weak standards of the Financial Action Task Force or the Global Forum won’t solve things either. As we’ve long warned, these standards have advised governments to build houses on sandy soil – it’s shouldn’t come as surprise then when walls begin to crumble.

Beneficial ownership vs legal ownership

Most companies have very simple structures where the legal owner (ie shareholder) directly owns and controls the company. In this scenario the shareholder is also be the beneficial owner. This information is publicly available in most commercial registries. That’s all good. The problem starts with complex ownership structures – ie where a company or legal entity is owned by many layers of entities spread across tax havens. These structures have been used by oligarchs, criminals and tax abusers to circumvent the rule of law. When it come to these structures, relying on just commercial registries is usually not enough to solve the problem.

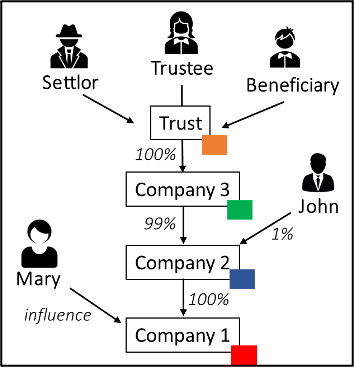

Consider the following complex structure, where each colour represents a different country of incorporation and where the real beneficial owners are Mary, John, the settlor and the beneficiary of the trust sitting at the top of the structure:

Relying on only legal ownership information held in commercial registries wouldn’t be enough to identify all these beneficial owners, even if (and this is a very big “if”) information on all the real owners was available in all relevant commercial registries.

The commercial register of country red would reveal that Company 2 is the legal owner of Company 1 (Mary wouldn’t appear in the commercial register). The next commercial register (country blue) would identify Company 3 and John as owners. The commercial register of country green would identify the trustee as shareholder (there might be no indication that the trustee is acting as a trustee on behalf of the trust, and could give the impression that she is the real beneficial owner). Even if the trustee declared the name of the trust to the commercial register of country green (which is unlikely), it would be even more unlikely that country orange has a trust register in which to find information on the settlor and the beneficiary. After a very time-consuming search, an investigating authority will at most identify just John and the trustee.

Current beneficial ownership registries aren’t that much better. Many of them include basic legal ownership information (eg Company 2) but not the full ownership chain (Company 3 and the trust) needed to confirm the declared beneficial owner on top. As for the beneficial owner information they hold, they would likely require the registering of the trustee, and in the best case scenario the settlor and beneficiary as well. But, Mary, who merely has influence (which may be hard to detect without advanced verification mechanisms) would likely avoid registration requirements, as would John. Only a truly effective beneficial ownership register would be capable of providing an overview of the whole ownership chain as shown in the figure.

Why beneficial ownership frameworks are flawed (even if in compliance with international standards) and how to fix them

As the brief describes, following the Financial Action Task Force’s recommendations, most countries identify as beneficial owners only those individuals who hold more than 25 per cent of the capital in a legal entity, and where no one is identified, those with “control via other means”.

Based on the goal of saving costs for companies and for firms, financial institutions and other obliged entities that must undertake customer due diligence, countries take a “small” data approach (rather than the “right-data” approach), asking for as little information as possible and hoping that this makes it easy and cheap to collect and verify information. There’s perhaps also a naive hope here that that the catch-all phrase “control via other means” will capture all relevant individuals while asking for little. This supposedly cost-saving choice is a false economy and comes at a great cost: authorities are unable to obtain all the information they need, instead needing to spend considerable time to identify the real beneficial owners.

Instead, the brief explains that a no-threshold approach (ie requiring the identification of any beneficial owner with at least one share or vote), coupled with more extensive details to be collected (eg information on those with a power of attorney or with exposure to a company’s economic performance) is the only way to ensure that authorities will have all the beneficial ownership information they need when the need arises. This way, authorities can readily analyse the information they hold to reveal undisclosed relationships, properly conduct investigations into crimes, and detect crimes that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Importantly, as this brief will show, implementing a no-threshold approach does not add costs: even a framework with a 25 per cent threshold presupposes that anyone holding directly or indirectly at least one share has been identified. This is the only way to aggregate all holdings and determine which of those passed the threshold. Switching to a no-threshold approach would require no additional work in identifying direct or indirect shareholders.

Busting the claims against a no-threshold approach

The sandy soil governments were advised to build their beneficial ownership frameworks on is the “25 per cent or more” threshold. The single most effective action governments can take to strengthen their beneficial ownership frameworks is switch to a no-threshold approach, following the examples of Argentina or Ecuador. This would identify as a beneficial owner any individual who has at least one share or vote in a legal entity – and eliminate the transparency escape hatch that is making beneficial ownership registers ineffective today.

Opponents to the no-threshold approach have made some arguments pushing back against the approach. The brief and the table below responds in detail to these.

Proportionality

Claim: Requiring “all” individuals to be registered (because no thresholds are applied) is by definition disproportionate.

Our response: There are plenty of cases where regulations apply to “all”: all legal owners must be identified with the commercial registry, all parties to a trust must be identified as beneficial owners. In many countries, all individuals must obtain a national ID, all taxpayers must file tax returns, all individuals wanting to drive must obtain a driving license, etc.

Necessity

Claim: A definition without thresholds does not pass the necessity test because an individual with 1 per cent or less of the shares would not be in control of the company and would thus not be responsible for any crimes.

Our response: Thresholds are deliberately exploited by criminals and those who want to remain hidden from authorities, undermining the whole purpose of beneficial ownership transparency. A person with even a 0.01 percent interest in a listed company (eg Apple) would have no control whatsoever over the entity, but that that tiny percentage could be worth millions of dollars. Identifying this person could be relevant to money laundering, corruption, tax evasion, etc.

Presumption of innocence

Claim: Preventive collection of data and pattern-finding violate criminal law principles. Looking for patterns to investigate specific individuals before suspicions exist violate the principle that “the suspicion leads to the investigation” rather than the other way around.

Our response: Crime prevention is just as important as its prosecution. There is no need to wait until a criminal act or wrongdoing happens in order to act. Crime prevention does not affect the presumption of innocence. Most legal frameworks put a lot of emphasis on prevention, not because they consider all individuals as future criminals or victimisers but to prevent them from becoming such.

Trust in government

Claim: Some human rights organisations and activists distrust what they believe governments will really do with the collected information, eg target vulnerable populations or political opponents.

Our response: State authorities aren’t necessarily the problem. Oligarchs, high net worth individuals and entities who are often more powerful than countries, pose a bigger risk to democracy, equality and the rule of law. A no-threshold approach is a way to protect minorities and vulnerable individuals by ensuring that powerful individuals won’t be able to escape the rule of law by creating complex ownership structures.

Securing data against hacks

Claim: All databases can be hacked. Collecting and centralising a trove of personal data on individuals related to legal vehicles creates a high hacking risk.

Our response: Although all systems could possibly be hacked, this has not stopped people from using banks, apps or password storage services. There are multiple privacy enhanced technologies that could be applied to reduce the risk of hacks or misuse, and to run analytics without sharing confidential information.

Ability to process data

Claim: Authorities are already overwhelmed with data and are often unable to process it effectively. There is no point in filing even more data with authorities because they won’t be able to use it.

Our response: The complete collection of beneficial ownership data is supposed to be handled by technology, algorithms, big data analysis, etc, and not necessarily through manual analysis. Complete data would create a deterrent effect, just as the implementation of automatic exchange of bank account information did.

Conclusion and recommendations

An effective beneficial ownership framework would secure sufficient information to identify all individuals who may turn out to be relevant, after running advanced analytics to detect undeclared relationships and other red flags. Most of the proposals of this brief originate from the Tax Justice Network’s Roadmap to Effective Beneficial Ownership Transparency. This new report explains why these proposals are necessary.

In a nutshell, the proposals include the following:

1. All legal vehicles should fall within the scope of registration – without exceptions.

2. A “necessary” data approach should be applied, rather than a “small” data approach. This would ensure that all individuals who are related to a legal vehicle are identified whenever they:

a) Have control, ownership or derive benefits from a legal vehicle;

b) Have at least one share, vote, right to benefits, interests or exposure through financial instruments (ie without applying thresholds); or

c) Have control via other means based on a non-exhaustive list such as power of attorney over the entity or its assets.

3. All “necessary” details should be required. In addition to basic identity details (name, address, nationality, date of birth), more details should be collected, such as: politically exposed person (PEP) status, tax residencies and nationalities (eg based on golden visas), identity of direct family members, price or value or reason for becoming a beneficial owner (eg price of transfer of shares), source of beneficial ownership (eg transfer of shares, apportionment as trust beneficiary.)

4. The full ownership chain should be obtained and verified, up to each individual with at least one share.

5. Charge fees for verification of complex structures. As a way to discourage complex ownership structures with too many layers and shareholders (which may increase costs for those collecting beneficial ownership information), financial institutions and beneficial ownership registries should be allowed to charge fees per layer and per shareholder for any entity that wishes to be incorporated or open a bank account.

6. Proper verification responsibilities. Countries should take an active role in beneficial ownership registration and verification by having the beneficial ownership register collect information on the full ownership chain down to each beneficial owner with at least one share, as well as cross-checking data and applying advanced analytics to detect red-flags (eg based on individuals’ declared income, income patterns for the neighborhood where the person is based, etc). This would reduce costs for financial institutions, which should be required to conduct some additional verification (not generally available to authorities) such as checking who administers the bank account, withdraws money from an ATM or from whom and to whom bank transfers are made.

Related articles

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

The State of Tax Justice 2025

Follow the money: Rethinking geographical risk assessment in money laundering

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention