Andres Knobel ■ ‘Strong on risks, loose on solutions’: our response to FATF consultation on Recommendation 24

The Tax Justice Network’s submission to the Financial Action Task Force’s open consultation on Guidance on Recommendation 24 on beneficial ownership transparency for legal persons is published in full below.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in charge of the Recommendations on Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) has opened a consultation on the Guidance to Recommendation 24 on beneficial ownership transparency for legal persons.

We have sent written submissions and participated in calls on the reform of Recommendation 24 and recently on Recommendation 25 (on beneficial ownership for trusts and other legal arrangements). Now, the FATF is inviting feedback on their proposed Guidance to Recommendation 24.

Our view

In a nutshell, the proposed guidance looks comprehensive on the risks, but rather loose on the solutions. It resembles the Bible, where every possible ‘sin’ (risk) is mentioned, but the solutions must first be sought out throughout its many pages and even then, may be subject to interpretation. So many “could”-s or “may”-s, all with equal weighing, would hardly put the fear of god-‘bad’ ratings into national governments. Instead, much clearer and to-the-point lists, similar to the “10 Commandments”, should be included. Section 10.1 on “Example features– Public authority or body holding beneficial ownership information” is an excellent example of what is needed. It deserves much more prominence in the guidance. Just like the 10 Commandments, it could become a pretty good summary of “the path of Good”.

Some major issues that require improvements:

- Bearer shares. The whole point of the Reform of Recommendation 24 was to require the registry approach because the other two approaches (relying on information collected by companies or obliged entities) was found to be insufficient to ensure timely access to beneficial ownership information. It thus makes no sense that in the case of bearer shares (one of the biggest risks to transparency), one of those two “obsolete approaches” is still allowed to be applied. The FATF Guidance contemplates that, for pre-existing bearer shares, ownership information could be held by enablers (eg lawyers, banks) and made available to authorities only on request. In other words, endorsing secrecy for pre-existing bearer shares.

To put this in perspective, the fact of requiring a register of beneficial owners for regular shares, but allowing secretive bearer shares to be held by lawyers and enablers is like throwing the baby out while keeping the bathwater. On top of everything, the Guidance offers Switzerland as an example of best practice. Of all countries that effectively prohibited pre-existing bearer shares, the Guidance mentions Switzerland which, as explained by the Financial Secrecy Index, gave an excessive time of 5 years for bearer shares to comply and even an additional 10 years to claim economic compensation for non-compliant bearer shares (until 2034!).

The only solution for pre-existing bearer shares is to demand that – within 6 months to one year – they must be converted into registered/nominated shares or registered with a government authority. Otherwise, they should be considered worthless papers without any legal rights. - Nominees. Nominee directors may still be needed in very specific circumstances, such as when institutional investors or a group of shareholders have a right to appoint one director in a company. The nominee director will represent and act on behalf of the corporate or institutional shareholder. In this case, sufficient information should be registered on the nominee status of the nominee director, the identity of the nominator and the nominator’s beneficial owners. In addition, these nominee directors should be subject to licensing. Unlike the Guidance’s provisions (paragraph 144, b.III) information on the nominator and its beneficial owners should always be registered with a government authority, rather than made available on request.

As for nominee shareholders or nominee directors who represent or act on behalf of just another individual, especially those with a “signature for sale”, they should be prohibited altogether. There should be economic and criminal sanctions against the nominee and the nominator for violating the prohibition, as well as measures to discourage nominators from using nominees to begin with, such as establishing the “constitutive effect” of registration (ie to consider the informal nominee to be the absolute owner of the shares and thus able to rip off the nominator).

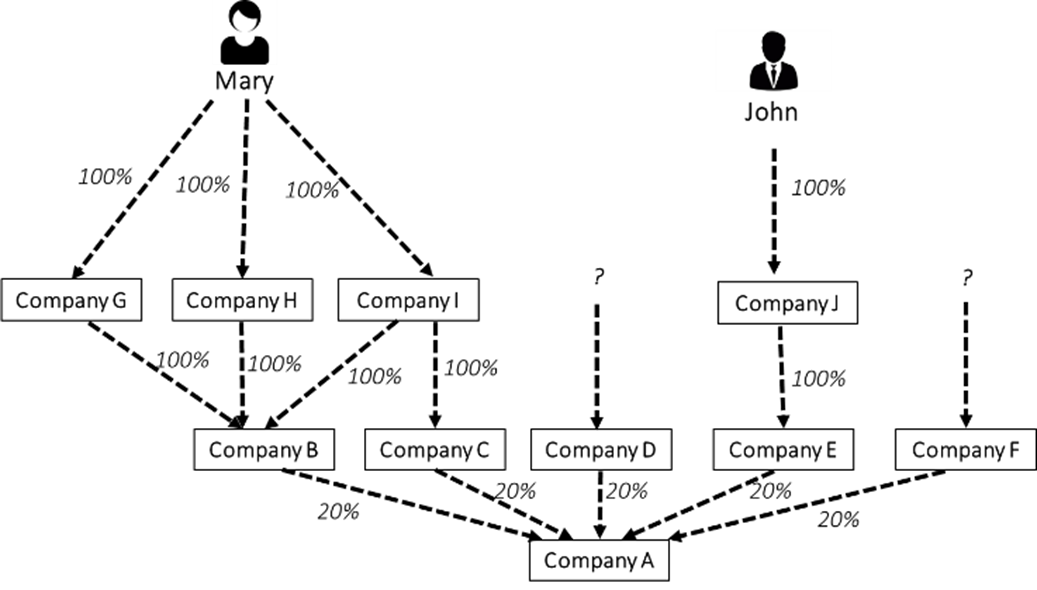

Importantly, the Guidance footnote 25 of page 40 should be deleted because it creates a secrecy risk. Although nominee shareholders should be prohibited in all cases, if countries are to establish licensing or transparency requirements, these should apply to absolutely all nominees, regardless of their interests in the legal persons. Footnote 25 suggests that nominees who hold interests below the threshold to be considered a beneficial owner need not be subject to any transparency or licensing provision. This is a huge mistake because the beneficial owner could have divided their shareholdings into many nominees or legal persons. For instance, John could indirectly have 50 per cent of the shares in Company A through five nominee shareholders, each with 10 per cent. None of the nominees would pass the threshold to be considered a beneficial owner of 25 per cent. However, it is only when considering all the nominators of all nominees that one would realise that John must be a beneficial owner. If footnote 25 were implemented, countries would never find out about John’s existence and would assume that each of the five nominees represent a different individual nominator. - Private foundations. For private foundations that have a similar structure to trusts the Guidance (para. 44 and 53) doesn’t require that all parties must be identified. It only offers an incomplete list of potential parties, and it even allows countries to cherry pick from that incomplete list which includes the “founder, beneficiaries, members of the management and an individual who has the right to exercise (or actually exercises) significant influence over the running of the activities of the foundation”. Instead, the EU AMLD rightly considers that the same definition and criteria applied to trusts (identification of all parties including the settlor, trustees, protector, beneficiaries and any other individual with effective control) should also be applied to private foundations, so that all the parties to the private foundation must be identified: founders, members of the council, protectors, beneficiaries and any other individual with effective control over the foundation. The Guidance should also consider the latest amendments to the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS) which proposed covering indirect beneficiaries, eg those who don’t appear on any document but whose expenses are effectively paid out by the trust or foundation, such as credit card expenses or tuition fees.

- Listed companies. As described by our paper on Beneficial ownership and listed companies as well as Beneficial ownership and investment funds, information held by stock exchanges is usually not sufficient to be classed as beneficial ownership data for two main reasons. First, even when forms may be called “the beneficial owner form” (as in the US securities exchange commission), they actually refer to a different term and different criteria (ie not necessarily a natural person). Second, the stock exchange or the transparency requirements established by the financial regulator are usually related to investor protection rather than anti-money laundering (sometimes exempting registration by large shareholders who are not intending to use their voting power). For this reason, listed companies should not be exempt from beneficial ownership registration. However, it is not enough to cover them, unless thresholds are lowered (because it is very unlikely that an individual will hold more than 25 per cent over a listed company or investment fund). In fact, even tiny holdings of 0.01 per cent over a listed company may be worth millions of dollars and thus relevant for anti-money laundering purposes (as well as for tax issues). For this reason, the FATF should follow the examples of Argentina and Ecuador, which require the identification of natural persons or beneficial owners who hold at least a dollar-value interest in the listed company or investment fund.

Argentina’s Resolution 4697/2020 of the tax administration requiring beneficial ownership registration, Art. 2, paragraphs 3 and 4:

In the cases in which the reporting subject lists its capital on stock exchanges or official stock markets with a public listing, it must only inform as beneficial owner the human persons who are owners or holders of the capital that own, directly or indirectly, at least one TWO PERCENT (2%) of the shareholding composition or a valuation of said participation greater than the equivalent of FIFTY MILLION PESOS (ARS 50,000,000) [USD 300,000], considered as of December 31 of the reporting year, whichever is less between both parameters; or, failing that, it must inform as such those individuals who by other means exercise final, direct or indirect control.

For the purpose of identifying the subject that has the character of beneficial owner, investment funds must apply the provisions of the preceding paragraph in all cases, whether or not they trade their shares on stock exchanges or official stock markets with public listing.

Ecuador established similar provisions under Arts. 5.2 and 6 of Resolution by the Tax Administration 536/2016 requiring the identification of all shareholders up to a natural person (similar to a beneficial owner, considering only the ownership element).

Proposals to reform the Guidance

1) Expand the scope to cover any foreign legal person with a local participant or holding any type of registrable asset

Section 2.2 proposes examples of “sufficient links” that a foreign legal person may have in relation to a country in order to require beneficial ownership registration.

First, the list should not be subject to each country’s discretion (ie “could” choose) but it should be a clear set of conditions that must trigger beneficial ownership registration.

The criteria mentioned between a) and e) are fine, but point d) should also cover holding any registrable asset, while the “significance” condition should only apply to assets not subject to registration, such as works of art. Our proposed amendments in bold:

d) Has significant real estate or other investment in the country, including any asset subject to registration, such as ownership of high value commercial or residential real estate, securities market investment or other assets. For assets not subject to registration (eg art works), they should be subject to registration if they have significant value. Significant here could be determined with reference to the average price of the real estate/corresponding asset market in the country, or the quantity of real estate held;

The list should also include having any local participant who is resident in the country:

f) Has a local participant, including a shareholder, beneficial owner, director, founder, protector, beneficiary, individual with a power of attorney, etc.

2) Risk assessment should include exploratory analysis and the assessment of the Financial Secrecy Index

Section 2.3 on Risk assessment includes paragraph 18 with a very good list of steps. The only problem is that it is again discretionary rather than a requirement.

Step a) could be improved to require statistics and exploratory analysis, similar to what we did analysing UK companies’ structures, so that countries are able to determine normal vs outlier company structures considering the number of layers, type of legal vehicles of each layer, number and nationality of legal vehicles and beneficial owners, as well as distribution of interests, votes or shareholdings, eg is it 50-50%, or 99-1%? Our proposed amendments in bold:

a) Collect and analyse registration statistics (e.g. incorporation volumes and trends) on all types of legal persons that can be created under their national laws as well as statistics on the structure of legal persons (e.g. number of layers, nationality and type of legal vehicle of each layer; number and nationality of beneficial owners as well as their nature and distribution, such as 50-50% or 99-1%, etc).

Paragraph 19 proposes countries to consider risks of foreign persons by looking at FATF blacklists or UN sanctions lists. The paragraph should also include the Financial Secrecy Index, which offers a list of loopholes in the legal framework of more than 140 jurisdictions in relation to legal and beneficial ownership registration of companies, partnerships, trusts and foundations. Most of the findings are summarised by the State of Play of Beneficial Ownership Registration paper.

3) Require disclosure of the full ownership chain to address complexity risks

Section 2.5 reflects on the risks of complex ownership structures. We have published a report with many ideas on how to address complexity, from requiring justification to outright prohibition above certain risk factors (eg involvement of tax haven structures, bearer shares in the ownership chain, etc). At the very least, the Guidance should impose on countries the requirement to disclose the full ownership chain up to the beneficial owners.

4) The beneficial ownership definition and the criteria to determine who is a beneficial owner

Section 4 deals with the beneficial ownership definition. As we have expressed many times, based on the very same FATF Glossary, the definition is not based exclusively on “control” but also on ownership. This means that ownership should not refer only to “controlling” ownership.

As the State of Play of Beneficial Ownership Registration report shows, many countries are using three elements (ownership, control or benefits) rather than only “control”.

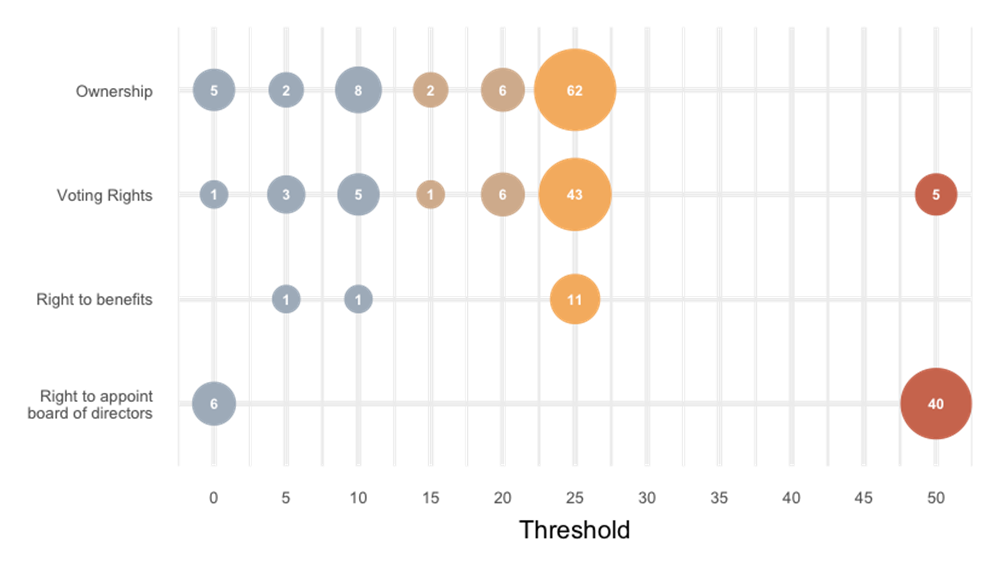

As for thresholds, although it is welcome that Section 4.2 considers establishing thresholds lower than 25 per cent, the mere consideration of that is not sufficient. As the chart above shows, some countries are already implementing no thresholds at all (expressed by the threshold “zero”). In addition, as described by the paper “The Beneficial Ownership Definition for Companies – Challenges and Opportunities”, NEBOT Paper 4, 2022, there is no additional cost in determining the beneficial owner when establishing no thresholds.

As illustrated by the next figure, even if a country establishes a definition using the 25 per cent threshold, the only way to determine who has more than 25 per cent of the shares is to know who has at least one share, so that all shareholdings are aggregated in order to confirm who passes the threshold. In the following figure, the available information is insufficient to register Mary and to decide not to register John. Though Mary already holds at least 40 per cent of the shares, laws require the specification of the precise number of shares, so it will still be necessary to determine the owners of Companies D and F to confirm whether Mary has more indirect shares over Company A. By the same token, the only way to discard John as a beneficial owner is to know exactly who owns Companies D and F. In other words, regardless of the threshold, as long as the definition covers direct or indirect ownership, it is necessary to identify all individuals who hold at least one share.

Although some could argue that the second test of the definition (control via other means) would cover individuals who are (deliberately) below the thresholds, common practice suggests that most companies (and financial institutions) identify beneficial owners based only on the first test of thresholds, without checking for control via other means, which may be hard to prove or discover. Given that any threshold can be circumvented, and there are cases of circumventing even 5 per cent by creating 21 companies (each with less than 5 per cent), the only real solution is not to apply thresholds for ownership or voting rights.

In addition, consistent with Section 4.1 and 4.3 (paragraphs 35 and 44), “interests” or “ownership” and “control” should not be limited to direct holdings of shares or membership, but should also include exposure or possibility to influence via convertible stock, call or put options as well as other financial instruments. This is a broader interpretation of “interest” which is established by the US beneficial ownership registration law, the Corporate Transparency Act.

5) More verification mechanisms: alert beneficial owners, zero-knowledge proof for non-resident beneficial owners and refocus discrepancy reporting

Section 7 explains many of the challenges and mentions some general frameworks for verification, but is too flexible on measures that must be implemented. Our 2019 paper on Beneficial ownership verification is still applicable. Two of our proposals should become mandatory:

- Proactively contacting the beneficial owner to ensure that they are aware and confirm their status as beneficial owner. This would help prevent cases of stolen identities. Importantly, the beneficial ownership registry should contact the beneficial owner based on any other government’s records of an email or mobile phone or address, rather than any declared information as part of beneficial ownership registration because the declared information may refer to the impostor.

- Zero-knowledge proof for non-resident beneficial owners. While countries may cross-check information on resident beneficial ownership against other government databases (eg tax records, natural person register, etc), they don’t have data on non-residents. For this reason, the FATF should propose mechanisms for zero-knowledge proof automated exchanges, where the beneficial ownership register sends a query to a foreign country’s database to confirm whether the declared information by a non-resident matches the foreign country’s records. For instance, the UK beneficial ownership register could send an automated query to Germany’s database regarding a German beneficial owner: “Hans declared to be born on X data, live on Y address and have Z tax identification number. Does this match Germany’s records?”. The German database would either confirm or reject the values, without disclosing the correct values in case of rejection. In such case, the UK register would ask the German beneficial owner to correct their data with Germany’s official registries, before they are allowed to be registered as a German beneficial owner of a UK company.

- Discrepancy reporting. The FATF should establish rules to distinguish basic discrepancy reporting to be done directly on the beneficial ownership register (eg there is one missing beneficial owner) versus actual suspicious transaction reports because of suspicions of money laundering, in which case the beneficial owner should not find out they are under investigation. However, it would be useful for obliged entities to be alerted that a beneficial owner or a company has been subject to a suspicious transaction report, so they can treat it with caution.

At the same time, for discrepancy reporting to be useful, rather than focusing it on typos or minimal mistakes, the beneficial ownership register should provide all reliable information on the full ownership chain, and the financial institution should alert on discrepancies not based on what the customer declared, but on what the financial institution determines. For instance, the financial institution may have information on the real residence of the beneficial owner (eg if they visited them at their house or if they know where the beneficial owner’s children go to school) or they could be aware of who has a power of attorney over the bank account or who withdraws money. This information is much more relevant than the name being spelled in different ways.

6) Interconnection or one central register for all types of legal vehicles and levels of ownership

As regards Section 10 (paragraph 79), the FATF should require that information on all legal vehicles (companies, trusts, partnerships) and levels of ownership (legal ownership, beneficial ownership) should be held by the same central register (or by a unified platform that interconnects and centralises information from all other registries) to prevent inconsistent information.

7) Public access, especially by journalists and civil society organisations

It is welcome that the Guidance (paragraphs 86 and 107) invites countries to consider public access, though this should become an obligation. The EU Court of Justice recognised in November 2022 that journalists and civil society organisations, as well as persons doing business with firms, have a legitimate interest to access beneficial ownership information. These stakeholders should have access to beneficial ownership information in all countries.

As for access by foreign authorities (paragraph 166), online registries should disclose the full ownership chain and allow searches not only by name of the company or the beneficial owner, but also by residence (or at least address) of the beneficial owner, so that foreign authorities may easily obtain information on all of their residents holding interests in the respective country.

Related articles

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

Two negotiations, one crisis: COP30 and the UN tax convention must finally speak to each other