Andres Knobel ■ Beneficial ownership transparency: how to fix a serious secrecy loophole in the automatic exchange system

Automatic exchange of bank account information is an important transparency tool to address tax evasion and other tax issues. It could also be used to tackle other types of illicit financial flows including money laundering, corruption, or the financing of terrorism, if only the OECD were to stop restricting its use for tax purposes only. However, automatic exchange of bank account information is especially useful when it includes information on the “beneficial owners” of bank accounts, meaning the natural persons who ultimately own, control or benefit from the bank account. Otherwise, money launderers and tax dodgers could keep everything hidden from authorities.

Among the many identified loopholes of the automatic exchange system under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS), (including exclusion of low-income countries, golden visas, etc), one big loophole makes it possible to hide the existence of foreign accounts by using legal vehicles such as companies or trusts. This loophole works because the beneficial owner of an account is not always reported under the OECD’s standard (CRS) and is never reported by the US under the inter-governmental agreements (IGAs) related to the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA).

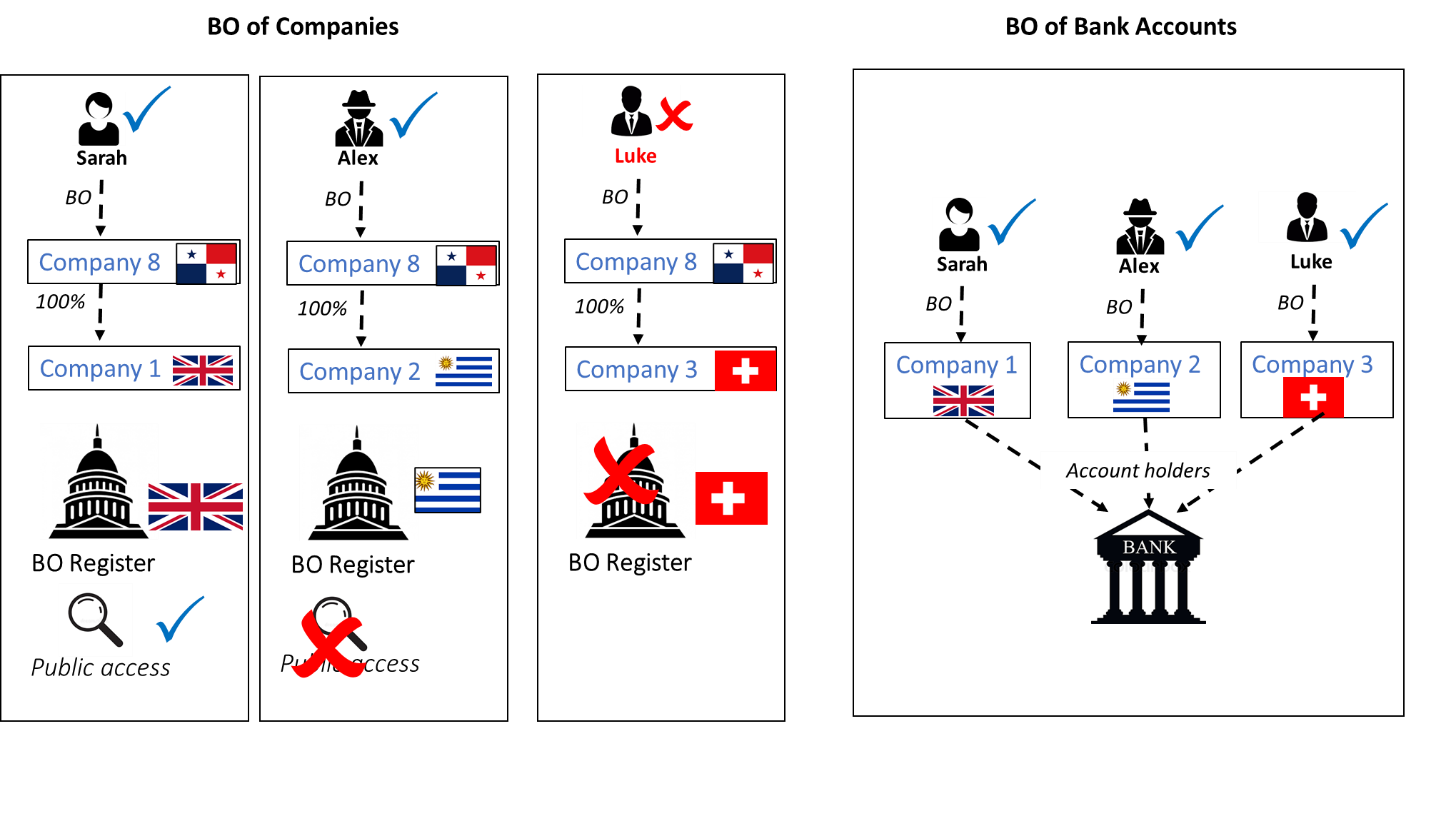

Beneficial ownership of companies and beneficial ownership of bank accounts

Beneficial ownership information involves identifying the natural persons who ultimately own, control or benefit from legal vehicles, eg companies, trusts and foundations. In turn, these legal vehicles may own assets such as real estate or bank accounts. Beneficial ownership information of a company can be obtained at the moment the company is created, or it may be collected when the company acquires an asset, eg a house or a bank account.

Without complete beneficial ownership transparency, anyone trying to keep their identity, assets and income hidden from authorities, including any Russian oligarch trying to avoid sanctions, can easily do so by operating and holding assets through legal vehicles, particularly complex ownership structures.

Perfect global beneficial ownership transparency would mean that all countries offered online free access to beneficial ownership information on any legal vehicle, eg any company, trust or foundation. This way, by also knowing the assets (eg real estate or bank account) owned by an entity, it would be possible to determine the beneficial owner of such an entity and thus the beneficial owner of the underlying asset. Unfortunately, that is not the case in most countries.

As for beneficial ownership transparency of legal vehicles at the time they are incorporated (created), the UK was one of the first countries to offer free public online information on beneficial owners of companies. A growing number of countries are starting to set up public registries, especially in Europe. However, most countries that have beneficial ownership registries don’t give public access to that information (eg Uruguay ). Finally, many countries still lack even a law requiring beneficial ownership of companies and other vehicles to be filed with a central registry (eg Switzerland).

Beneficial ownership of any bank account held by a company may still be achieved even if a country doesn’t collect beneficial ownership of companies when they are incorporated. Financial institutions must collect beneficial ownership information on their customers (including customers which are companies) as part of the due diligence process for (i) anti-money laundering purposes and for (ii) automatic exchange of information purposes. In other words, as the next figure shows, banks must collect beneficial ownership information on all companies holding a bank account, even if that company didn’t have to file beneficial ownership information with a central register at the time the company was incorporated.

Loopholes in the collection of beneficial ownership by banks

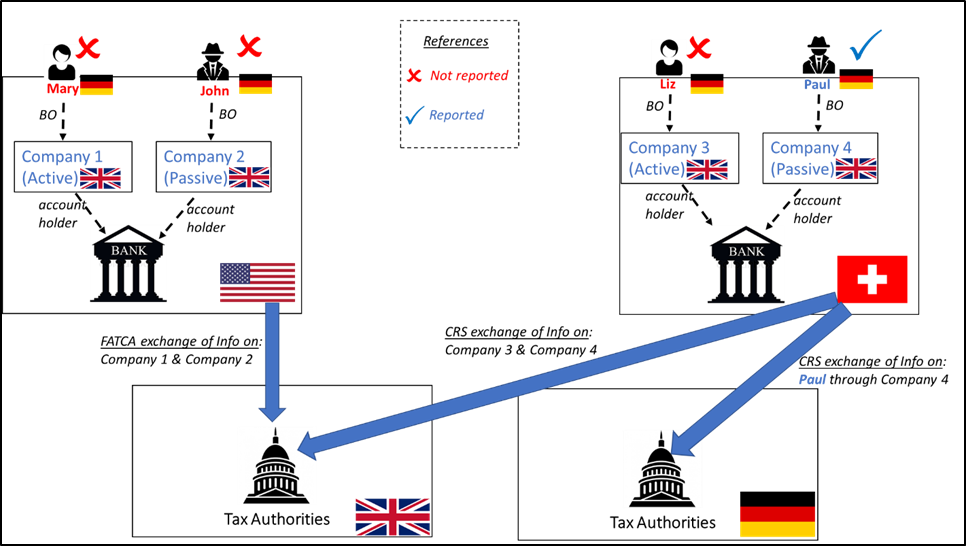

Under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard for automatic exchange of information, a beneficial owner (called a “controlling person”) must only be identified and reported by a financial institution if the account holder is an entity classified as “passive” (because most of the entity’s income or assets are passive, eg interest, dividend, royalties, etc). In contrast, where an account holder is considered an “active” entity, eg because most of the entity’s income is from the provision of goods or services, the bank would not need to identify and report its beneficial owners for automatic exchange purposes. It is not clear why the OECD chose this exemption for active entities (given that banks should be collecting beneficial ownership information of “active” entities for anti-money laundering purposes in any case). The exemption for active entities may be because of pressure from the private sector to exempt some types of companies in order to make compliance with the standard easier. It could also be the case that the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard has a focus on tax evasion, which may be more of a problem of beneficial owners of passive entities, than a problem of active entities that are taxed at the entity level. The “Introduction” to the Common Reporting Standard may be implicitly suggesting that only passive entities would be abused by individuals to avoid reporting. [1] Whatever the reason for this difference between active and passive entities, the problem is that it creates secrecy (lack of automatic exchange at the beneficial ownership level) which can be exploited not just to engage in tax evasion, but also for the purpose of money laundering, corruption or other financial crimes.

The next figure illustrates different scenarios showing when information is exchanged and at which ownership level. In essence, the figure shows that the only information exchanged at the beneficial ownership level refers to exchanges under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard and only regarding Paul because he is the beneficial owner of a “passive” entity (Company 4). Liz’ information is not reported to Germany (her country of residence) because she is a beneficial owner of an “active” entity (Company 3). In the case of Mary and John, their type of entity is irrelevant (passive or active) because the US never exchanges with other countries information at the beneficial ownership level, despite the US demanding this information from its partner countries (non-reciprocal exchanges).

How to obtain information on unreported accounts

Obviously, the easiest and most direct way to get information at the beneficial ownership level is to make the US comply with its commitment to achieve full reciprocity and exchange as much information as it receives – basically to send information to other countries at the beneficial ownership level. At the same time, the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard should close its loophole and require the reporting of beneficial owners’ accounts also for “active” entities. However, until these changes to the standard take place, countries can solve this loophole bilaterally.

Unless Mary, John and Liz decide to voluntarily disclose their accounts in Switzerland and the US, German authorities won’t find out about the existence of these accounts. However, there are a few steps Germany could follow to try and obtain this information.

- Check the beneficial ownership registries of countries offering public access, eg the UK to find out information about entities owned by German beneficial owners. This way Germany can discover that Mary is the beneficial owner of Company 1, John of Company 2, Liz of Company 3 and Paul of Company 4. (Germany should already know about Paul’s ownership of Company 4 because this information will have been received from Switzerland as part of the automatic exchange of information system under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard).

In our example, Germany wouldn’t receive any information from companies 1, 2 and 3 because they are classified as “active” entities so their beneficial owners (Mary, John and Liz) were not reported. Without that information on the beneficial owners, there was no link connecting these companies to Germany because companies 1, 2 and 3 are from the UK, so only the UK would receive information about them. However, in “real life”, there could be other reasons why Germany didn’t receive any information on companies owned by German beneficial owners. It may be the case that these companies simply didn’t hold a bank account (unlikely), or that they held accounts in countries excluded from the automatic exchange system (eg Bolivia).

Although Germany cannot know why it didn’t receive information on these companies 1, 2 and 3 (Germany would simply have not received any information about them), it could take steps to find out if by any chance there are foreign companies held by German beneficial owners (in our example, companies 1, 2 and 3) that do have foreign bank accounts.

- Nudge letters. Finding out that Mary, John and Liz own British companies 1, 2 and 3 doesn’t mean that Germany knows anything about their US and Swiss bank accounts. However, German tax authorities could send a “nudge” letter to Mary, John and Liz saying “we know you have a British company, make sure you have reported any foreign income or asset, including a bank account you hold through that British Company”. This could work. Most likely however, Mary, John and Liz wouldn’t fall into that trap so easily. Either way, the automatic exchange system is to confirm data to prevent relying solely on self-declarations.

- Make a group request to the UK about foreign accounts held by companies 1, 2 or 3. Based on the fact that British companies 1, 2 and 3 have German beneficial owners (Mary, John and Liz), Germany could make a “Group request” to the UK to ask whether any of these companies were mentioned in any of the information received by the UK as part of automatic exchange of bank account information based on either the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard or FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act) with the US. In the best case scenario, the UK would inform Germany: “actually, yes, we received information that Company 1 and Company 2 have accounts in US banks (with X account balance and Y income) while Company 3 has an account in a Swiss bank (with X account balance and Y income)”. To offer even more information, the UK should also inform Germany whether any of these three British companies have accounts in the UK (this information wouldn’t have been received by the Common Reporting Standard or the FATCA, but the UK should be able to find out if any of its banks has an account for either of the companies).

Countries, eg the UK, may reject the request claiming that it is a fishing expedition which is prohibited under the OECD standard for exchanges “upon request”. However, Germany could claim it’s not a fishing expedition by showing evidence, eg based on leaks, that in the past German beneficial owners have been using British or other foreign companies to hold foreign unreported assets. Ideally, if countries agree to engage in these exchanges as proposed below, countries wouldn’t refuse to exchange information based on the prohibition of fishing expeditions.

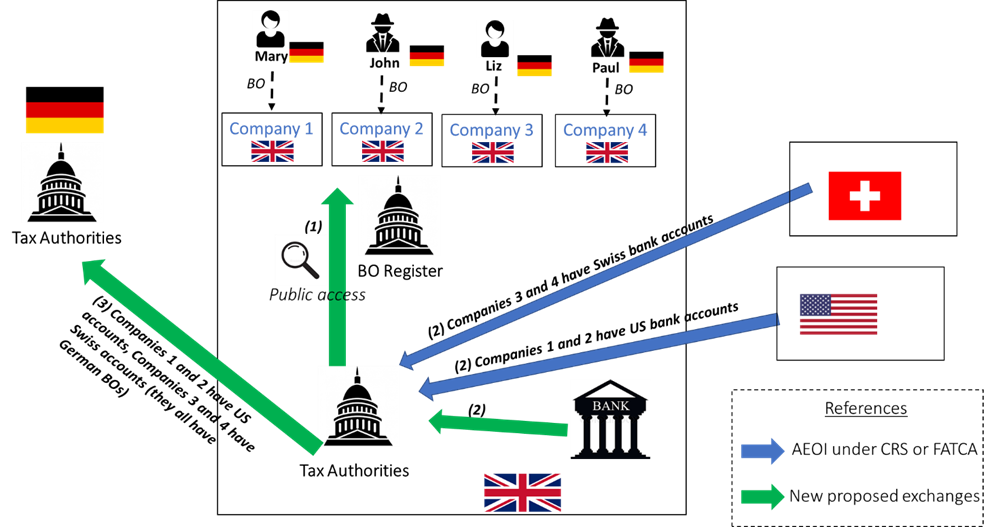

From group requests to automatic or spontaneous exchanges

One way to improve the previous process would be to replace the need for Germany to search other countries’ beneficial ownership registries and make a group request. Instead, each jurisdiction, eg the UK, should automatically or spontaneously exchange relevant information with other countries. In this case, the UK would look into its own beneficial ownership register to identify every entity that is owned by a non-resident beneficial owner. It would then check whether these entities have bank accounts in the UK, or whether the UK received any information about them pursuant to the Common Reporting Standard or the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act. After doing this, it would report all this information to the corresponding country of residence of the beneficial owner.

In the example above, the UK would tell Germany “we checked our own beneficial ownership register, as well as information on foreign and local bank accounts. We found out that these four companies (1, 2, 3 and 4) have German beneficial owners and they have accounts in Switzerland and the US. These are the details…”. [The UK would be incentivised to do this, because Germany would return the favour. German authorities would identify German companies that have British beneficial owners and they would report back to the UK information on the global bank accounts held by these German companies with British beneficial owners].

Improving exchanges within the EU and taking advantage of discrepancy reporting

The EU could also start implementing this process. One option would be to use the momentum of the discussions on the changes to the anti-money laundering framework (the AML Package) which deals with beneficial ownership and bank account information. Another more likely option would be to establish this mechanism under the Directive on Administrative Cooperation (DAC) which deals specifically with automatic exchange of bank account information within the EU under “DAC 2”.

This “system upgrade” to exchange information on accounts held by beneficial owners of “active” entities (or on accounts held in US banks) should soon become easier because EU countries are supposed to interconnect their beneficial ownership registries under the requirements of the 5th anti-money laundering directive known as AMLD 5. This interconnection of beneficial ownership registries should provide each EU country with information on any resident individual who is a beneficial owner of an EU entity. In that case, the only extra step would be for each EU country to check whether those entities with non-resident beneficial owners are “active” and have local bank accounts, or foreign bank accounts (based on the information they received via FATCA or the CRS).

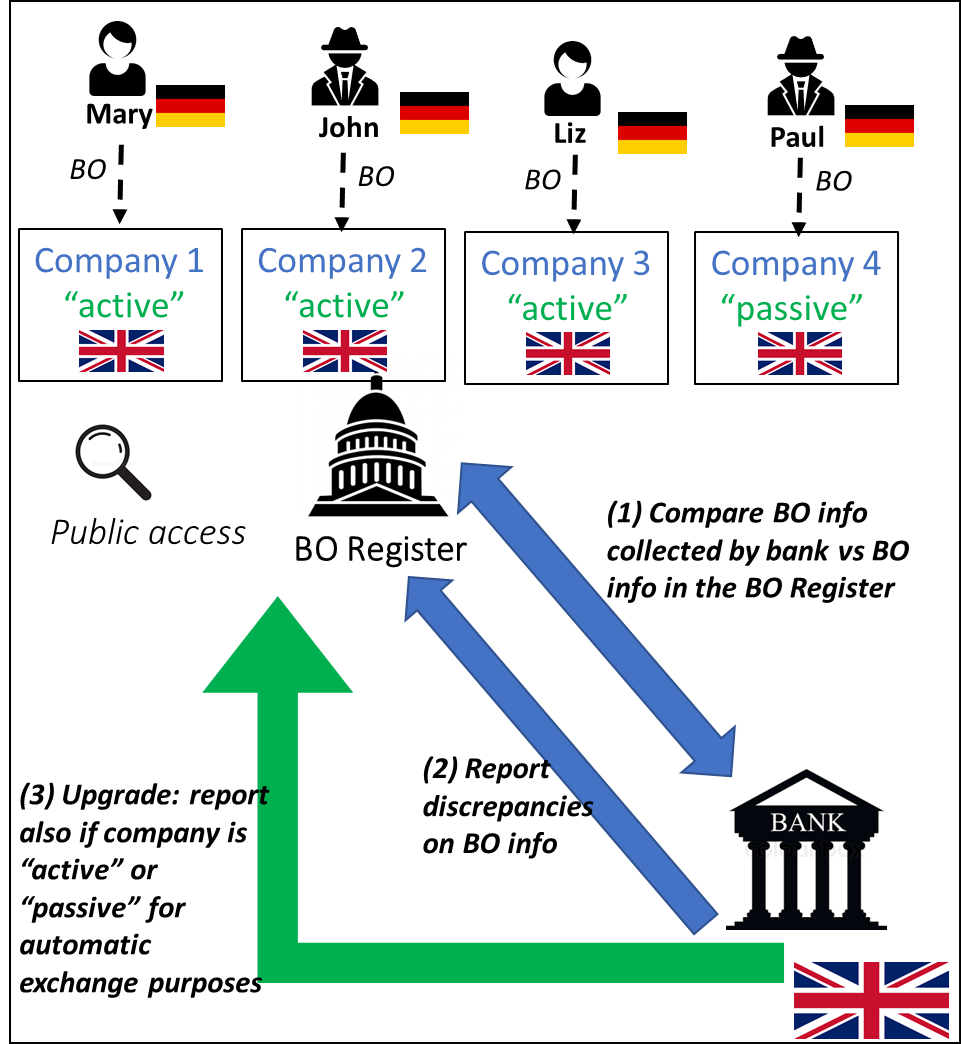

In addition, another EU “upgrade” could help in the identification of “active” entities. As explained above, a central beneficial ownership register may at best indicate the identity of the beneficial owners of companies, but the register would provide no information on whether that company should be classified as “active” or “passive” for automatic exchange purposes, or whether that company has a bank account. However, another feature of the AMLD 5 for “verification of beneficial ownership” could be exploited to add detail on the entity classification.

Under the AMLD 5, as a way to improve the accuracy of information contained in the central registries of beneficial owners of companies, banks are required to check the information contained in the central registries and compare it with the information that they collected on their customers as part of their due diligence process, and then report any discrepancies that may arise. This discrepancy reporting that is already taking place could be “upgraded” by requiring banks to also report the status of a company as either “active” or “passive”, based on the classification that a bank did for automatic exchange purposes. This way, central beneficial ownership registries would be able to disclose to authorities whether any company is “active” or “passive” so that authorities may make a group request of information on bank accounts regarding only “active” entities. (In reality, until the US fully reciprocates, Germany would still need to make a group request on all companies – active and passive – because the US won’t report information at the beneficial ownership level even if the entity is “passive”. However, for companies with bank accounts in any other country, finding out whether companies are “active” may save some time and resources).

[On a completely separate note, if central registries disclosed the status of companies as “active” or “passive”, this could be effective in addressing problems in the limited liability system. This is unrelated to the automatic exchange system or tax evasion or money laundering, but it would be important for equity and social justice]

Countries without public beneficial ownership registries

The whole process would be more complicated in cases where beneficial owners are using an entity from say Uruguay rather than the UK, because Uruguay doesn’t offer public access to beneficial ownership information on their companies. In this case, Germany could sign an agreement with Uruguay, or have an informal arrangement where Germany will share information with Uruguay on any German entity with a Uruguayan beneficial owner, and in return Uruguay shares information with Germany on any Uruguayan entity with German beneficial owners. The second step (which could be done at the same time) would also be to check whether the country received information about foreign accounts held by any of these entities, based on FATCA or the Common Reporting Standard, and then alert the other country. In other words, Uruguay would first identify Uruguayan companies with German beneficial owners. Then it would check whether any of these companies have bank accounts anywhere in the world (based on the information received via FATCA or the Common Reporting Standard). Uruguay would then share this information with Germany, and Germany would then reciprocate.

Conclusion

Although the easiest and most direct way would be to change the automatic exchange system under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard and the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA)to exchange beneficial ownership information in all cases, countries may take these bilateral measures to help each other obtain relevant information which is not directly available through automatic exchanges. This process would streamline the synergies between beneficial ownership registries and automatic exchange of information towards more transparency on beneficial ownership of assets.

[1] “A comprehensive reporting regime requires reporting not only with respect to individuals, but should also limit the opportunities for taxpayers to circumvent reporting by using interposed legal entities or arrangements. This means requiring financial institutions to look through shell companies, trusts or similar arrangements, including taxable entities to cover situations where a taxpayer seeks to hide the principal but is willing to pay tax on the income.” (page 12)

Image credit: “networkunlockedcloseup.jpg” by CyberHades is marked with CC BY-NC 2.0.

Related articles

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

When AI runs a company, who is the beneficial owner?

Insights from the United Kingdom’s People with Significant Control register

13 May 2025

Uncovering hidden power in the UK’s PSC Register

New article explores why the fight for beneficial ownership transparency isn’t over

Asset beneficial ownership – Enforcing wealth tax & other positive spillover effects

4 March 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024