Nick Shaxson ■ The UK is breaking up Facebook/Meta and (almost) nobody noticed

We’re sharing the latest edition of The Counterbalance, the newsletter of the Balanced Economy Project, a global antimonopoly initiative. This article was originally published here. You can sign up for their newsletter here.

Frances Haugen, the celebrated Facebook whistleblower, briefly became a bit of a cult hero for exposing the giant platform’s toxic role pushing algorithms that encourage teenage suicides, threaten national security, go easy on drug cartels and drug traffickers, foster riots, or destabilise democracies – then lying about it and continuing to push its intensely profitable and addictive (“like cigarettes“) product.

But her testimony contains a fatal flaw: she wants us to ‘fix’ and regulate Meta, the company formerly known as Facebook. This is what the company wants, and indeed is actually asking for, because it distracts us all from the only thing that will really make a difference: breaking its power.

Until we do that, the giant will lobby, sidestep and bulldozer its way around (or through) any rules, laws, taxes, regulations and “fixes” that we throw at them.

Lawyers have known this for decades. Jack Blum, a prominent U.S. antitrust lawyer in the 1960s and 1970s, now in his 80s, remembers how companies would prefer to negotiate settlements with regulators, instead of having the law applied to them:

“That became a ‘regulatory’ approach,” Blum told us. “Regulation became the preferred approach of the industry people – because they knew they could push the regulators to do what they wanted.”

There are several ways to break monopolists’ power, including of course with appropriate and effective regulation. But very often, especially with a dominant giant, the simplest and most effective first step is to break it into smaller, less powerful pieces. Since the combined entity is stronger and more powerful than the sum of its parts, breakups can be very good ways to curb power. (For those skittish about breakups, read this.)

And that is exactly what the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is now doing, with a decision on November 30 that Meta must sell Giphy.

Giphy produces those irritating (or, if you’re more open-minded, hilarious) GIFs, or “graphics interchange format” moving images that pop up like distracting mushrooms through our increasingly electronic lives.

Having just acquired Giphy, Meta must now sell it “in its entirety” to an approved buyer. Yes, this is only snapping off a small fragment of the Meta-behemoth, but this counts as a breakup.

As a reminder of how significant this is, the GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) have acquired more than 1,000 firms in the past 20 years, and, as the EU’s former chief competition economist, Tommaso Valletti, told The Counterbalance last year, “zero of those transactions were blocked — and 97 percent were not even assessed by anybody. These are extreme, ridiculous numbers.”

That is a ratio of 1,000 to zero, globally. (In the UK the ratio for 2008-2018 was 400 to zero.) Neither the Americans, the Europeans, the British, nor anyone else, had blocked anything in this space. Ridiculous indeed.

Now Giphy raises this from zero to one. So yes, this is a big deal. Yet outside of technocratic circles and a few specialist journalists, almost nobody noticed!

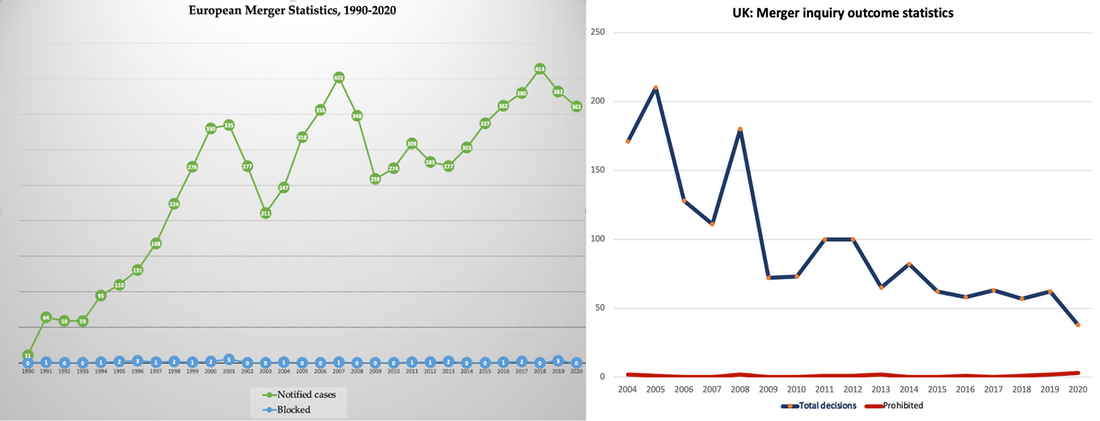

And the significance of this goes far beyond Big Tech. Look at these two graphs:

Source: European Commission; CMA; author’s calculations. Of 8083 mergers notified to the EC since 1990, just 30, or 0.4 percent were blocked. The UK has blocked 17 out of 1,565, or 1.1 percent, since 2004.

They suggest that our regulators, captive to a bad Chicago-School paradigm, don’t block mergers, let alone break them up. (It was the same in the US for decades, until this year.) The last significant forced breakup anywhere was of the telecoms firms AT&T – forced by US regulators, in 1982-4.

In a nutshell, the whole corrupt EU system essentially reflects the desires of monopolists.

All this may be a surprise to some given all the approving (often fawning) media coverage of EU Competition boss Margrethe Vestager. Those EU fines on big tech firms have been absorbed with barely a burp.

A Brussels insider described the Giphy case to us as “a bit of an earthquake,” adding “I was surprised how little buzz it got at [Europe’s competition authorities.] I really have a feeling that the antitrust establishment on both sides of the Atlantic is hoping to weather the neo-Brandeisian storm with as little change to the prevailing Chicago school paradigm as possible.”

In the cloud, floating above the law

A striking aspect of the Facebook case is that the company didn’t even bother waiting for the CMA’s merger review before going ahead with the deal, perhaps hoping simply to bounce the CMA into accepting it by jumping the gun. (In the US, they seem to have used financial chicanery to get around the rules on Giphy – and the EU, for its part, didn’t review it.) Some companies seem to think they are above the law. Meta is far from alone: the US firm Illumina seems to have been just as arrogant when it announced its acquisition of Grail, even before the EU had completed its review. In Australia recently, the top competition regulator Rod Sims, recently said that companies were sometimes “contemptuous” of the regulator.

*This paragraph has been updated** Thankfully, the CMA has shown some spine here. (China has taken a more muscular approach too. The United States Federal Trade Commission is also seeking a Meta breakup.)

The green shoots of Giphy

The Giphy case raises big questions. For one thing, is the UK regulator within its rights, and can it, force a global breakup of a super-powerful US firm?

Yes: it is, and it can. The CMA already recently blocked a global merger of two US tech firms, Sabre and Farelogix. And with Meta, an altogether more formidable proposition, it has serious backup. Tim Cowen, a well known UK competition lawyer, explained that if the CMA sticks to its guns, it can get the job done:

“Ultimately the CMA applies for a court order. That is issued and non compliance is contempt of court for which jail beckons – and brings the entire foreign judgements and enforcement system into play. That works for court orders internationally and is the basis of the world trade system.”

So, while Brexit has entailed many costs, it has in this case potentially freed the UK to make a decisive break from Europe’s pro-monopoly approach.

Yet this is no slam-dunk, of course. The company has stunning lobbying power and influence: not least the fact that its key lobbyist, Nick Clegg, is a former deputy Prime Minister of the UK.

A bad-tempered struggle is now underway: Facebook denounced the CMA in September, and the CMA in October fined the newly named Meta £50.5 million for “consciously refusing” to provide information. Meta has already appealed the CMA decision and as Politico notes, it “will spare no effort or billable hour to try to stop the breakup.”

Will democracy prevail? We hope so. When the European Commission blocked the GE-Honeywell merger 20 years ago, they were faced with “the most intense politicking old hands there have seen. . . . .There were journalists, lobbyists and lots of arbitragers from Wall Street calling constantly.” So much so, that as one (especially astute) observer put it:

“That decision set off a concerted campaign by the US to get the EU to adopt a more merger-friendly, ‘economic’ approach to merger review . . . . That campaign worked and its legacy is a track record of hardly any mergers blocked in the last two decades.”

This US government, now showing impressive anti-monopoly chops, surely won’t interfere in UK politics like that. But another might. And the CMA faces another major political headwind: a gaping hole where there should be support.

Civil society: a gap

While the Giphy case has got plenty of attention in narrow technocratic circles, in wider society it’s barely registered. That’s a stunning gap, given the importance of this case.

*the following paragraph has been updated*

For example, when the CMA publicly requested comments on the case, almost no genuine independent civil society voices submitted comments. (An exception, which is not listed on the relevant CMA page, came from Privacy International, which made an excellent and expert submission.1) The think tanks, which seem to have dominated commentary, that did seem to have unclear funding sources (are they funded by Meta?) and the two academics admitted openly that they have consulted for Facebook.

And if you delve into the submissions and other lobbying around the case, you’ll see how other-worldly (and often nonsensical) the arguments are. For example:

- “Facebook . . . supplied reassurances to address the concerns raised by the CMA” (yes, and we’ve a bridge to sell you);

- [this] is the type of over-enforcement that . . . depresses economic growth, and chills innovation” (Meta is an arch monopolist, for crying out loud: it is well known that monopoly reduces growth and kills innovation not to mention the damage it’s inflicting on our democracy, on vaccination rates, and so on);

- “Giphy cannot be considered a competitor to Facebook” (where to start . . .)

- This will hurt the UK’s competitiveness. (Nonsense.)

- “The CMA is sending a chilling message to start -up entrepreneurs: do not build new companies because you will not be able to sell them.” (See earlier comment on monopolists slaughtering innovation: Facebook has famously run a “copy – acquire – kill” strategy.)

And so on. To cut a long story short, we’re in the odd situation outside the US where regulators are growing more activist than civil society. There are civil society actors making arguments here about power, such as Article 19, but they are rare. The civil society dog isn’t barking. This is dangerous, and we’re dedicated to changing this.

How and why to break up the giants

If regulators want to block or unwind mergers, they confront an industry of economists, lawyers, courts, lobbyists, usually a high burden of proof and a pervasive pro-monopoly worldview. (The arguments get wonkish and complex, though in Giphy’s case, the CMA fortunately side-stepped getting bogged down in econometrics and deployed more sensible “theories of harm” (pp7-9) than some cases have hinged on in the past.)

To start with, let’s tackle some common misconceptions about breakups.

First, some people, mostly on the political left, dislike them (and competition policy more generally) because they think that the primary purpose is to increase market competition, a process that they are suspicious of (for reasons good and bad, which we won’t get into here.) Yet the prime purpose here is is to break Meta’s power, so that it can be regulated – and yes, healthier competition reinstated – in the public interest.

Second, many people think that if you break a social media platform into pieces, then, well . . . how will I be able to watch that kitten fall hilariously into the yoghurt tub, if we’re now on different parts of a broken-up platform?

One answer is the principle of inter-operabilitywhere regulators force platforms to break open their walled gardens and ensure that if you are on one platform, you’ll be able to watch that kitten in yoghurt from another. (To illustrate, email or phone calls are interoperable: you can call or email anyone using any service.) And if one platform tries to force you to hand over democracy-bending amounts of data, inter-operability lets you migrate to healthier one, without losing sight of the kitten. (The EU’s incoming Digital Services Act is likely to require this, though it often falls woefully short.)

Third, when some people think of breakups they think of Mickey Mouse in the film Fantasia, where a magic broom runs amok so he cuts it up with an axe – only to face a plethora of smaller magic brooms, and a situation even more out of control.

Effective breakups don’t work like that. Instead, you separate companies as you might cut a diamond: along natural fracture lines (which could be, for example, based on previous acquisitions; or along management reporting lines, etc.)

The acquisition of Giphy had taken a familiar and thus important fragment of the internet and inserted it into a walled garden where it became juiced up with massive market power. Since the combined entity became more powerful than the sum of its parts, a well-judged breakup curbs power overall.

As the CMA put it, with Giphy:

people are less able to control how their personal data is used and may

effectively be faced with a ‘take it or leave it’ offer when it comes to signing up to a platform’s terms and conditions.”

That’s raw power. According to the CMA, the Meta platforms (Facebook, Instagram etc.) account for nearly three quarters of social media use in the UK, and half of all display advertising revenues (pp9-10). Meta can use this power to force us into a devil’s bargain to sign away our data – potentially with the kinds of consequences that Frances Haugen reminded us of. For example, it and Google have been effectively massacring local journalism at a global scale. If news organisations instead had a wide range of platforms to negotiate with, the scales could tip dramatically, potentially injecting billions into these crucial pillars of our democracy.

People make various other arguments against breakups. Many simply can’t be bothered with the kerfuffle, or they think that it would be like unscrambling eggs, or “inefficient,” or that it “punishes success”, or, perhaps most commonly, “this is about a bunch of free stuff, and we don’t care.”

Well, it’s not free. The UK estimates that digital advertising costs each household £500 a year through more expensive goods and services, which is like a £14 billion tax effectively monopolised by Facebook and Google. (See this, or this.) And as for punishing success, Facebook is earning an estimated 50% return on capital (p8) largely not for making better stuff, but because it kills or eats its competitors.

A warning from history

Mark Zuckerberg wants to bind us into a private “metaverse” of virtual reality, conspiracy theories, puppies in yoghurt, teenage suicides, comedy skits, viral memes, thrilling immersive space voyages, and political violence back on earth. He may feel that, as dictator of the Zuckerverse, he is benevolent. We, and we hope you, disagree.

“The liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself,” U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously declared in 1938. “That, in its essence, is fascism — ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or by any other controlling private power.”

As he spoke, something along those lines was massing in Germany, whose economic structure was intensely monopolised then. Sure, there were plenty of other reasons why Hitler came to power — and the world is entirely different today. But make no mistake: dispersed and balanced economic ecosystems support political pluralism and balance, and on the flip side, monopolisation will likely entrench any autocrat’s power and give them powerful economic levers to increase political dominance. Just look at what Viktor Orban is doing in Hungary right now, or the symbiotic relationship between monopolising oligarchs and the regime of Belarus’ dictator, Alexander Lukashenko. Look in any country, in fact, where oligarchs have carved up the economy.

The dangers are especially acute when it comes to flows of information — which is what Meta and Big Tech are all about. That three quarters of UK user time spent on social media probably underestimates the problem, as anyone who has kids with smartphones knows: social media’s dazzling allure violently drags attention away from piano lessons and myriad healthy other things, and glues it into social media.

A fully fledged and successful metaverse will make this even worse. We have allowed Mark Zuckerberg, an unelected person apparently drunk with power, effectively to set the rules for how billions of people communicate with each other.

And this is, very obviously, very dangerous. As the US anti-monopolist Matt Stoller put it:

A regulatory overlay in some ways would worsen the problem, because it would explicitly fuse political control with market power over speech and it would legitimize the dominant monopoly position of Facebook.”

The right is suspicious of such a regulator because they are afraid of what Biden and the left would do with it. But I suspect that suspicion isn’t out of place on the left either. If you are a Democrat, imagine, for instance, if Trump were able to pick a regulator for social media, to negotiate with Zuckerberg on how to run global discourse.

Better not to have such concentrated power in the first place.”

Finally: update on a US lawsuit to break up Meta, including Whatsapp and Instagram. This, if it succeeds, could be yet more significant. More on this, another time.

Related articles

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

Two negotiations, one crisis: COP30 and the UN tax convention must finally speak to each other

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Taxation as Climate Reparations: Who Should Pay for the Crisis?