Will Snell ■ All in for tax justice: what our supporters said

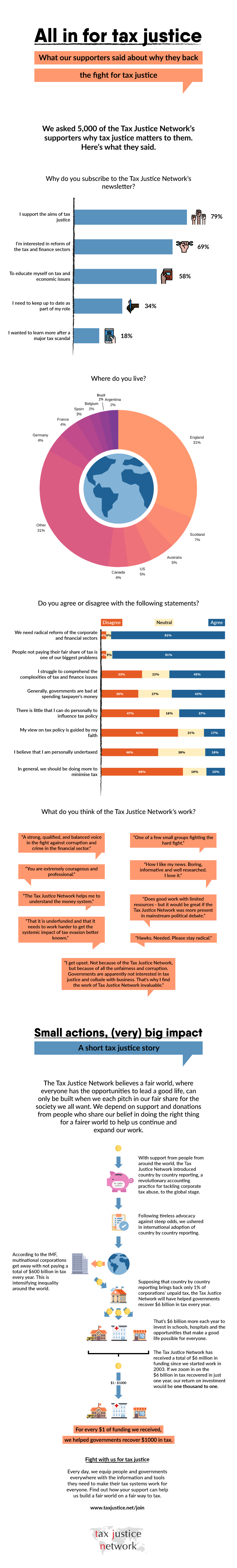

We asked our newsletter subscribers to complete a short survey to help us make sure the Tax Justice Network is delivering the research, stories and opportunities that matter to them, in the ways that help them best engage in tax justice.

We’ve put together an infographic summarising what people said about our work and why tax justice matters to them. You can view the infographic below.

Based on people’s feedback, we’ve created a new supporter scheme for individuals who want to make a one-off or regular donation to the Tax Justice Network. Our supporters will help us to undertake our research and campaigns to expose corruption, fight vested interests and build a fairer global economy by providing us with predictable, unrestricted funding.

Fighting for tax justice

Corporations and wealthy elites have made historic levels of inequality possible by taking over the tax systems of countries around the world, turning tax policy into a tool that prioritises the interests of the wealthy instead of treating the needs of all members of society as equally important. The Tax Justice Network believes a fair world, where everyone has the opportunities to lead a meaningful and fulfilling life, can only be built when we each pitch in our fair share for the society we all want.

Every day, we equip people and governments everywhere with the information and tools they need to reprogramme their tax systems to prioritise the needs of all members of society, over the desires of corporate elites. We need your support, now more than ever, to continue the fight for tax justice. With your help, we need to raise £300,000 to continue our research, advocacy and communications work in 2020, as part of our four-year strategy.

Your donation will make a big impact. We estimate that every $1 invested in the Tax Justice Network may have yielded $1,000 in additional revenues for national governments to spend on reducing inequalities and building strong public services.

Related articles

UN tax convention hub – updates & resources

The Bitter Taste of Tax Dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss Swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

Taxing windfall profits in the energy sector

14 January 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

I´m interested in the FATF recommendations, especially 8, 10, 24 and 25 that are about the beneficial ownership.

Have there been any enforcement actions to date based on Country by Country reporting?

You are “estimating” that funding you brings lots of money back to various governments, but as far as I can see your claims are without evidence.

This is also to be considered when the EU, IMF and OECD have all stated that the data from country by country reporting is not useful in and of itself, and cannot be used directly or indirectly to assess tax compliance.

Which in essence means it is near useless. So all this article is is the TJN fishing for more money.

The Most Socially Just Tax

Our present complicated system for taxation is unfair and has many faults. The biggest problem is to arrange it on a socially just basis. Many companies employ their workers in various ways and pay them diversely. Since these companies are registered in different countries for a number of categories, the determination the general criterion for a just tax system becomes impossible, particularly if it is to be based on a fair measure of human work-activity. So why try to do this when there is a better means available, which is really a true and socially just method?

Adam Smith’s (“Wealth of Nations”, REF. 1) says that land is one of the 3 factors of production (the other 2 being labor and durable capital goods). The usefulness of a particular site of land is expressed by its purchase price and in the amounts that tenants willingly pay as rent, for its access rights. Land is often considered as being a form of capital, since it is traded similarly to other durable capital goods items. However it is not actually man-made, so rightly it does not fall within this category. Indeed, the land was originally a gift of nature (if not of God), for which all the people in the region should have equal rights for sharing in its opportunities for residence, accessibility and use.

However over many years, as communities became established and grew, the land has been traded as if it was an item of durable goods and today it is often treated as a form of capital investment. It is apparent that for a particular site, its current site-value greatly depends on location and is related to the community density in its region, as well as the size and natural resources that it can provide. Such bounty, often manifest in the exploitation of rivers, minerals, animals or plants of specific beauty and use are available only after infrastructural developments have made possible access to the particular place. Consequently, much of the land value is created by man within his society, by his need and ability to reach it and take from it materials, plants and live creatures, as well as the opportunities it provides for working space near to people. These advantages should logically and ethically be fairly returned to the community, for its general use within the government, as explained by Martin Adams (in “LAND” REF 2.).

However, due to our existing laws, the land is owned and formally registered and its value is traded, even though it can’t be moved to another place, like other kinds of capital goods. This right of ownership gives the landlord two big advantages over the rest of the community. He/she can determine how it may be used, or if it is to be held out of use for speculative reasons, until the city grows and the site becomes more valuable. Secondly the land owner enjoys the rent from a tenant or its equivalent if he uses the land himself. Speculation in land values and its rental earnings are encouraged by the law, in treating a site of land as personal or private property—as if it were an item of capital goods, although it is not, see Prof. Mason Gaffney and Fred Harrison: “The Corruption of Economics”, REF. 3.

Regarding taxation and local community spending, the municipal taxes we pay are partly used for improving the infrastructure. This means that the land becomes more useful and valuable without the landlord doing anything—he/she will always benefit from our present tax regime from which the land value grows. This also applies when the status of unused municipal land is upgraded and it becomes fit for community development. When this news is leaked, after landlords and banks corruptly pay for this valuable information, speculation in land values is rife.

There are many advantages if the land values were taxed instead of the many different kinds of production-based activities such as earnings, purchases, capital gains, home and foreign company investments, etc., (with all their regulations, complications and loop-holes). The only people due to lose from this are those who exploit the growing values of the land over the past years, when “mere” land ownership confers a financial benefit, without the owner doing a scrap of work. Consequently, for a truly socially just kind of taxation to apply there can only be one method–Land-Value Taxation.

Consider how land becomes valuable. Pioneers and new settlers in a region begin to specialize and this slowly improves their efficiency in producing specific goods. The land central to the new colony is the most valuable, due to its easy availability and least transport needed. After an initial start, this distribution in land values is created by the community. It is not due only to the natural land resources. As the city expands, speculators in land values will deliberately hold potentially useful sites out of use, until planning and development have permitted their more intensive use and for their values to grow. Meanwhile there is fierce competition for access to the most suitable sites for housing, agriculture, manufacturing industries, transport byways, etc. The limited availability of the most useful land means that the high rents paid by tenants make their residence more costly and the provision of goods and services more expensive.

Entrepreneurs find it difficult or impossible to compete with the big organizations who have already taken full advantage of their more central sites. The greater cost of access, or the greater expense in transportation from less costly outlaying regions, discourages these later arrivals. It also creates unemployment, causing wages to be lowered by the land monopolists, who control the big producing organizations, and whose land was previously obtained when it was relatively cheap. Consequently this basic structure of our current macroeconomics system, works to limit opportunity and to create poverty, see above reference.

The most basic cause of our continuing poverty is the lack of properly paid work and the reason for this is the lack of opportunity of access to the land on which the work must be done. The useful land is monopolized by a landlord who either holds it out of use (for speculation in its rising value), or charges the tenant heavily for its right of access. In the case when the landlord is also the producer, he/she has a monopolistic control of the land and of the produce too, and can charge more for this access right than what an entrepreneur, who seeks greater opportunity, normally would be able to afford.

A wise and sensible government would recognize that this problem of poverty derives from lack of the opportunities to work and earn. It can be solved by the use of a tax system which encourages the proper use of land and which stops penalizing everything and everybody else. Such a tax system was proposed about 140 years ago by Henry George, a (North) American economist, but somehow most macro-economists seem never to have heard of him, in common with a whole lot of other experts. (I would guess that they even don’t want to know, which is even worse!) In “Progress and Poverty”, REF. 4, Henry George proposed a single tax on land values without other kinds of tax on earnings, sales of produce, services, capital-gains etc. This regime of land value tax (LVT) has 17 features which benefit almost everyone in the economy, except for landlords, tax collectors and banks, who/which do nothing productive and find that land dominance and its capitalistic exploitation have their own (unjust) rewards.

17 Aspects of LVT Affecting Government, Land Owners, Communities and Ethics

Four Advantages for Government:

1. LVT, adds to the national income as do other taxation systems, but it should replace them. The author has shown in REF.5, that taxation of any kind is beneficial to the country as a whole due to its national income providing for more work too, but that when the tax applies to land the topology and spread of its effects are about 3 times as beneficial as when the same amounts of income are taken directly from labor.

2. The cost of collecting the LVT is less than for all of the production-related taxes–tax avoidance becomes impossible, because the sites are visible to all and who owns each site is public knowledge. The army of tax collectors who are opposing a similar set of lawyers, are no longer busy with tax loop-holes in the law, so the number of people more productively employed will grow and the penalty on the country of having complicated taxation is less.

3. Consumers pay less for their purchases due to lower production costs (see below). They can buy more goods and enjoy a raised standard of living. This creates greater satisfaction with the management of national affairs and more prosperity.

4. The national economy stabilizes—it no longer experiences the 18 year business boom/bust cycle, due to periodic speculation in land values (see below). The withholding of unused land is eliminated see item 7, so there is less need for the complications of frequent land sales, with developers searching and buyers hunting for unused sites.

Six Aspects Affecting Land Owners:

5. LVT is progressive—this tax depends on the site area as well as its position. The owners of the most potentially productive sites pay the most tax per unit of area. Urban sites provide the most usefulness and their owners will pay at greater rates, whilst big rural sites have less value and can be farmed appropriately, to meet their ability to provide useful produce. Small-holder farming closer to population centers becomes more practical, due to local markets and reduced distribution costs.

6. The land owner pays his LVT regardless of how his site is used. A large proportion of the present ground-rent from the tenants (who do use the land properly), becomes transformed into the LVT, with the result that the land has less sales-value but retains a significant “rental” value.

7. LVT stops speculation in land prices, because the withholding of land from its proper use is not worthwhile.

8. The introduction of LVT initially reduces the sales price of sites, even though their rental value can grow over a longer term. As more sites become available, the competition for them is less fierce and entrepreneurs have more of a chance to get started.

9. With LVT, land owners are unable to pass the tax on to their tenants as rent hikes, due to the reduced competition for access to the additional sites that come into use.

10. Speculators in land values will want to foreclose on their mortgages and withdraw their money for reinvestment. Therefore LVT should be introduced gradually, to allow these speculators sufficient time to transfer their money to company-based shares etc., and simultaneously to meet the increased demand for produce (see below, items 12 and 13).

Three Aspects Regarding Communities:

11. With LVT, there is an incentive to use land for production, transport or residence, rather than it being vacant and held unused.

12. With LVT, greater working opportunities exist due to cheaper land and a greater number of available sites. Consumer goods become cheaper too, because entrepreneurs have less difficulty in starting-up their businesses, and because they pay less ground-rent–consequently demand grows, whilst unemployment and poverty decrease.

13. Investment money is withdrawn from land and placed in durable capital goods. This means more advances in technology and cheaper goods too because the effectiveness of labor has been raised.

Four Aspects About Ethics:

14. The collection of taxes from productive effort and commerce is socially unjust. LVT replaces this national extortion by gathering the surplus rental income, which comes without any exertion from the land owner or by the banks–LVT is a natural system of national income-gathering.

15. Previous bribery and corruption for gaining privileged information about land, cease. Before, this was due to the leaking of news of municipal plans for housing and industrial development, causing shock-waves in local land prices (and municipal workers’ and lawyers’ bank accounts!)

16. The improved use of the more central land of cities reduces the environmental damage due to unused sites being dumping-grounds, and the smaller amount of fossil-fuel use (with its air-pollution), when traveling between home and workplace.

17. Because the LVT eliminates the advantage that landlords currently hold over our society, LVT provides a greater equality of opportunity to earn a living. Entrepreneurs can operate in a natural way– to provide more jobs because their production costs are reduced. Then untaxed earnings will correspond more closely to the value that the labor puts into the product or service. Consequently, after LVT has been properly and fully introduced as a single tax, it will eliminate poverty and improve business ethics.

References:

1. Adam Smith, 1776: “The Wealth of Nations”, UK

2. Martin Adams, 2015: “LAND– A New Paradigm for a Thriving World”, North Atlantic Books, California, USA

3. Mason Gaffney and Fred Harrison, 2005: “The Corruption of Economics”, Shepheard-Walwyn, London, UK

4. Henry George: “Progress and Poverty” 1897, reprinted 1978 by the Schalkenbach Foundation, New York, USA

5. David Harold Chester, 2015: “Consequential Macroeconomics—Rationalizing About How Our Social System Works”, Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbüchen, Germany