Nick Shaxson ■ Tax “stability” short-changes Burkina Faso

A couple of years ago we wrote a blog entitled Beware the siren song of “tax certainty, which took apart a widespread consensus that it is important for countries to embrace ‘tax certainty’ and ‘stability.’ These motherhood-and-apple-pie terms hide a world of mischief: not least the fact that this ‘certainty’ is usually a one-way ratchet.

In other words, companies love the ‘certainty’ that taxes won’t be raised, but they don’t need the ‘certainty’ that taxes won’t be cut. This one-way ratchet is generally a bad thing for the countries that embrace it, because it prevents them from raising taxes (or from implementing other beneficial policies such as social or environmental laws) when they need to do so.

One of the harshest varieties of this ‘tax certainty’ is obtained by companies in the minerals field, when they sign highly aggressive contracts containing ‘stabilisation clauses’ which guarantee that taxes won’t be raised. As the OECD and others have noted, these clauses are especially common in developing countries.

Now, from Finance Uncovered, in a joint investigation with l’Economiste du Faso and Cenozo, the West Africa investigative journalism unit:

“The impoverished citizens of Burkina Faso have missed out on an estimated $16.5m in gold mining royalties . . . thanks to a special low tax deal its former dictator made with a foreign firm.”

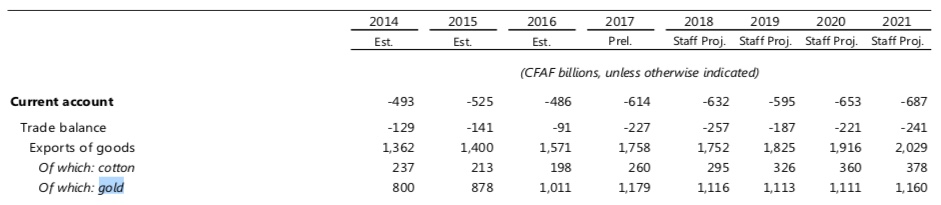

Burkina Faso is one of the world’s poorest countries. The firm in question, Norgold, is owned by one of Russia’s richest men, whose personal wealth is equivalent to half of Burkina’s GDP. And gold is a big deal for Burkina Faso, making up around three quarters of exports, as this IMF table shows (CFA 550 is worth about US$1):

Burkina, in a desperate quest to attract investment in its gold industry, for years set the rate for gold royalties, a central plank of the mining tax regime, at 3% (So if a company produced $1,000 worth of gold, it would pay $30 to Burkina Faso, whatever the production costs or profitability.) Three percent is considered very low by industry standards and after gold prices rocketed in the early 2000s, the government realised it was being short-changed and put in place a new regime in 2010, with a floating rate of up to 5%.

But the joint investigation byFinance Uncovered and L’Economiste of Burkina Faso uncovered a contract showing that in 1995, the previous owner of the Taparko mine, Canada’s High River Gold, successfully negotiated a deal with the previous regime of President Blaise Compaoré to fix the royalty rate at 3% for 25 years. When the government tried in 2011 to increase taxes, they hit the brick wall of the stability clause. Nordgold’s bosses wrote to the government to complain, and according to Halidou Bocoum, director of Nordgold in Burkina Faso, said they received confirmation of the “continuity of the tax regime”.

L’Economiste and its partners calculated the loss for this particular mine at $16.5 million. This may well be the case at other mines too, which would make the losses greater.

Kwesi Obeng, Oxfam International’s West Africa regional programme advisor, said the investigation again highlighted the ‘one-way ratchet’ problem with fiscal stability clauses.

“In Africa, as in this case of Burkina Faso, most fiscal stability clauses are asymmetrical.”

Indeed. Beward the siren song of tax ‘stability’ or ‘certainty’.

Defenders of such contracts say they are needed, to have a ‘competitive’ investment climate. But we are only too well aware of how easy it is to browbeat (and even corrupt) the governments of poorer, inexperienced countries into signing vastly unequal contracts. And on the subject of a ‘competitive’ tax regime for mineral-rich countries, well there’s a whole other set of arguments come into play. As we’ve said before, Do not listen to [mineral companies’] whining for tax cuts.

Related articles

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

The People vs Microsoft: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Can the UN succeed? Top questions about our State of Tax Justice report

Switzerland’s tax referendum is a choice between tax havenry and more tax havenry

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #66: الضريبة الموحدة على الشركات والفرص الضائعة