Andres Knobel ■ Country by country reports: why “automatic” is no replacement for “public”

A critical battle is currently being waged in the international tax policy arena over the implementation of country by country reporting, a reporting process that deters and detects tax avoidance by multinational companies, among other things, by requiring companies to provide a global picture of their activities, structures and the taxes that they pay. While country by country reporting would have been quickly written off just a few years ago, the practice is now widely accepted as necessary for the healthy functioning of economies. On the backfoot, some actors pushing to make the implementation of country by country reporting as toothless as possible are now claiming “confidentiality” concerns. But do their concerns have any merit or are they just crying wolf?

The side fighting for transparency in this current policy battle lost a round last week at the hands of Germany’s new finance minister, Olaf Scholz, at the EU parliament. In our view, Germany’s support of giving multinational companies and tax havens the power to veto any proposals on the implementation of county by country reporting sabotages European efforts to make companies be more transparent about their financial affairs.

Transparency NGOs want country by country reports to be made public. Big business and the OECD want the reports to be only viewed by tax authorities because they consider the reports “confidential”. Well, firstly, “confidential” is a rather subjective term and interpreted differently across different countries. The US president can opt to refuse to share his “confidential” tax return, while the income of any ordinary person in Sweden or Norway can be accessed by anyone. Perhaps ordinary Scandinavians are less afraid of being kidnapped than the US president, who’s protected by the Secret Service…

When it comes to country by country reporting, however, references to confidentiality seem to be a red herring rather than a genuine concern. If country by country reports were really that confidential, how could EU banks and companies in the extractive sector ever have been required to publish this country by country data in the first place? Even more so, why would Vodafone be willing to publish their own country by country report online when it’s not (yet) obliged to do so, as it has recently done?

If this whole fight isn’t about confidentiality, then what is it about? Let’s explore a bit more…

The position of the OECD and big business is that they want only tax authorities to access – via automatic exchanges – this country by country information they consider “confidential”. But that doesn’t make much sense in practice. If your worst “enemy” -the tax(wo)man- will already get your secrets, who cares if the lay person also finds out? Authorities are the only ones who can actually hold multinationals accountable in cases where they’re engaging in illegal tax avoidance or other wrongdoings (neither NGOs or journalists can impose fines or send someone to jail). So what’s the big deal?

Maybe big business isn’t afraid of authorities at all (perhaps because of the extent to which the OECD limits the use of the country by country reports by authorities). So who are they afraid of?

In these discussions, big business always mentions “competitors” gaining access to trade secrets. This argument does not fly for two main reasons. First, other big businesses will also have to file their country by country reports, and so it’s hard to imagine how big business A would lose out compared to big business B, if both have to disclose the same information about themselves. Second, companies engaged only in one jurisdiction are already filing the same information that multinational companies would be required to disclose in country by country reporting. Thus, the only “trade secrets” of relevance here appear to be sophisticated tax avoidance schemes that involve more than one jurisdiction. Surely nobody would argue that these are legitimate trade secrets that should be kept confidential?

What about small businesses? Small businesses lack the economies of scale (and bargaining power) of big business, so it’s hard to imagine big business losing out to small ones, unless the only real advantage that allows big business to be that big and spread out throughout the globe is the tax avoidance they’re engaged in (which is rarely available to small businesses).

What all this suggests is that big business is more afraid of NGOs and journalists who have no power to impose fines or send anyone to jail, but who may start public debates on whether the accounting and taxing schemes exploited by multinationals should be allowed to continue.

Maybe I’ve got it all wrong, and big business is actually afraid that NGOs may kidnap them? Or use all the basic aggregate information of their country by country reports to set up their own big businesses and take them out of the market?! No. I think what big business really fears is that public country by country reporting will deliver exactly what most people, if you asked them, want from them: accountability.

Information is power. If there’s anything that tax havens, big business, the OECD and criminals in general learnt from the Panama Papers, Swiss leaks and Luxleaks, it’s that public disclosure is dangerous. Not because of “confidential” information falling into the “wrong” hands (although transparency opponents will usually repeat this line endlessly, as a dogma). In fact, there are no reports of kidnappings of people whose bank accounts or corporate affairs were leaked (at the most, there were investigations by government authorities). Nor were there reports of bankruptcies of multinationals whose secret tax dealings with Luxembourg were made known. What they’re really afraid of is change. Of losing the upper hand they currently hold thanks to secrecy. Once scandals related to tax evasion, tax avoidance, corruption or money laundering become known, public outrage can lead to a change in the status-quo they protect so fiercely.

The OECD

Next question: why is the OECD, a club of rich countries, opposing public country by country reports?

The OECD has opposed public country by country reporting repeatedly throughout history, with some of its member states pushing the EU to back off from introducing it in the EU. Maybe the OECD doesn’t want to be ridiculed if the automatic exchange scheme developed by them (and then imposed on the rest of the world) might be changed by the revolutionary EU.

Or maybe the OECD simply fell in love with “its” idea of automatic exchanges. Don’t get us wrong; we like automatic exchange of information and we’ve actually been calling for it for years (way before the OECD did). But our longstanding support for “automatic” exchanges was in relation to the much flawed existing framework of “exchanges upon request”, where foreign authorities had to somehow obtain all the data themselves and only then make a request, which usually allowed them to merely confirm the accuracy of their already proven suspicions. Our request for automatic exchanges referred to actual confidential information such as banking information, but not to information that should be public, like beneficial ownership, country by country reporting, or tax rulings.

After coming up with the Common Reporting Standard for the automatic exchange of banking information, the OECD must have felt like it hit a goldmine and went fully “automatic”: automatic exchanges of banking information, automatic exchanges of country by country reports, automatic exchanges of tax rulings (they’re called “compulsory spontaneous exchanges” which in practice means they are automatic).

But why is the EU listening to the OECD so much and why is it afraid of moving way ahead on the issue of country by country reporting? After all, the EU recently approved the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive requiring public beneficial ownership registries for companies and widening transparency on trusts’ beneficial owners (in spite of the UK’s initial opposition). This Directive is far more transparent than the OECD’s Global Forum (and even the Financial Action Task Force) who require only beneficial ownership to be available. Both the OECD and FATF consider it enough not only if a government registry holds the information confidentially, but even if the very same company under investigation is the only one holding the beneficial ownership information!

The best reason why the EU needs not abide by everything the OECD says and suggests (e.g. automatic for all) is that many countries are already disregarding the OECD’s ineffective suggested measures. Instead they are publishing or at least ensuring access to information the OECD considers confidential and restricts its access to. Not only country by country reporting, but also another issue related to tax avoidance: crossborder tax rulings (such as the ones involved in Luxleaks).

In the case of tax rulings, our Financial Secrecy Index shows that Belgium, Brazil, Kenya and Mauritius already publish all unilateral crossborder tax rulings for free, while Australia, Denmark, Finland, France, Israel, Luxembourg, Netherlands, South Africa and Sweden do it for some of them, but not all.

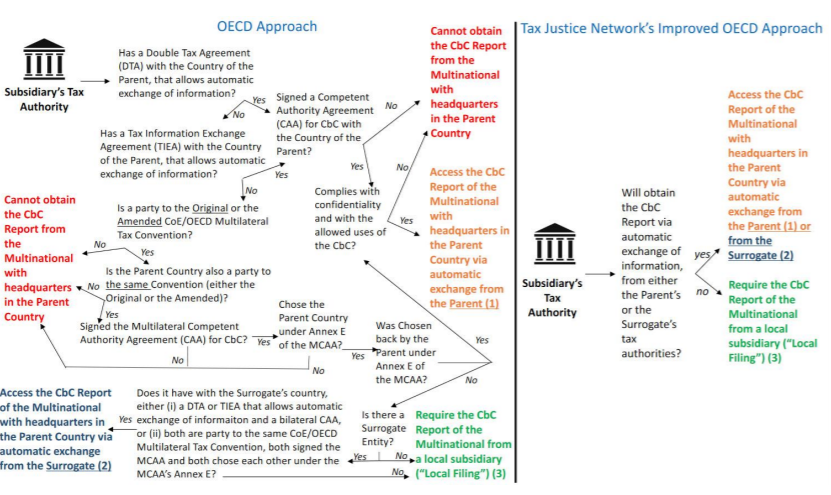

When it comes to accessing a country by country report, as we’ve described in this report, and shown in the graph below, the OECD framework for automatic exchange of country by country reports is very cumbersome, involving a complex treaty network of “parents” and “surrogates” for a two-page document (the country by-country report) that is unique for every multinational (the same country b -country report of say, Google, should be accessible to every country where Google operates). Most importantly, the whole system relies on having an international treaty with the country where each multinational is headquartered. That may be easy for the EU or for rich countries, but not for developing ones.

That’s why, until country by country reports are published online everywhere, there’s a second best case scenario which countries, especially developing countries, should follow. Instead of abiding by the OECD Model legislation, which highly restricts access to country by country reports, countries should establish rules that say, “If I cannot receive the relevant country by country report from another country via automatic exchange of information (regardless of the reason), the local subsidiary of the multinational will have to file their country by country report to our local authorities”.

Our Financial Secrecy Index reveals that many countries have done this, ensuring they will obtain the country by country report in more cases than those allowed by the OECD’s restricted approach (see table below).

Given all these visible cracks in OECD’s hegemony in the tax world, and given all the flaws in the arguments defending corporate secrecy: what then is it that the EU and the German government are waiting for?

| Jurisdiction | Details of regulations requiring local filing of country by country reporting (CBCR) |

| Australia | Local filing of CBCR is required whenever Australia doesn’t receive the information automatically from other countries (Australia Tax Authorities FAQ on CBCR, question 2.1) |

| Austria | While Austria’s law requiring filing of CBCR doesn’t explicitly state that CBCR will be required to be filed if it cannot be obtained automatically from other countries, at least Austria’s domestic law goes beyond the OECD model legislation and doesn’t require an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction. If there is no competent authority agreement with the ultimate parent, that is enough to require local filing (§ 5.(1).2, VPDG law). |

| Belgium | Belgium goes beyond the OECD model legislation and doesn’t require an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction to apply CBCR requirement to a Belgian resident group entity. If there is no competent authority agreement with the ultimate parent, that is enough to require local filing. |

| Canada | Secondary reporting mechanism is applied when certain conditions are satisfied. Canada goes beyond the OECD model legislation and doesn’t require an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction. If there is no competent authority agreement with the ultimate parent, that is enough to require local filing (Guidance on Country-By-Country Reporting in Canada 2017, p. 5). |

| China | According to PwC, local filing in China will be required if China doesn’t have an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction or even if it has such an agreement, if Taiwan doesn’t effectively receive the CBCR (PwC 2016) |

| Denmark | It appears that a tax resident company of Denmark shall file a CBCR beyond the OECD legislation, as long as Denmark cannot obtain it automatically, even if it has an international agreement with the parent’s jurisdiction. (Tax Control Act, Section 3B. This was confirmed by Deloitte. |

| France | While according to France’s Ministry of Finance there is no requirement to file the CBCR (TJN-Survey 2017), France has approved internal regulations that require local filing whenever an entity cannot demonstrate that another entity has been designated to file the CBCR in a country that will exchange information with France (Art. 223.C.2.b, Tax General Code) |

| Germany | According to Germany’s Ministry of Finance, Germany will require the filing of the CBCR in all cases (TJN-Survey 2017). In fact, Law AO § 138a, Art. 4 simply states that a CBCR has to be filed locally if Germany didn’t receive it otherwise. However, it appears that sanctions for failure to provide the CBCR do not ensure compliance. |

| Gibraltar | While Gibraltar’s law requiring filing of CBCR does’t explicitly state that CBCR will be required to be filed if it cannot be obtained automatically from other countries, at least Gibraltar’s domestic law goes beyond the OECD model legislation and doesn’t require an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction. If there is no competent authority agreement with the ultimate parent, that is enough to require local filing (Art. 10O.1.b, Income Tax Act 2010 Amendment Regulations 2017). |

| Hong Kong | According to Hong Kong tax administration, where the ultimate parent entity is resident in a tax jurisdiction which neither requires the filing of CbC reports nor has a QCAA in place with another tax jurisdiction, the group’s constituent entity in that other tax jurisdiction may be required to file the CbC report locally. Since Hong Kony doesn’t require an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s, it goes beyond the OECD legislation. |

| Iceland | Iceland domestic law goes beyond the OECD model legislation and doesn’t require an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction. If there is no international exchange of information agreement with the ultimate parent, that is enough to require local filing (Article 91(a) of the TSKL (Income Tax Act) (google translate) |

| India | A parent entity or an alternate reporting entity or any other constituent entity, resident in India, for the purposes of sub-section (2) or sub-section (4) of section 286 of the Income-tax Act, 1961 shall fill CbC report (10DB-4). |

| Ireland | Irish CbC rules include secondary mechanism. Rules are similar to OECD model legislation except no need an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction thus goes beyond it. Section 891H (as amended by section 24 of the Finance Act 2016) of the Taxes Consolidation Act 1997 (No. 39 of 1997), Art. 3(1)(b). |

| Italy | On 8 March 2017, the Ministerial Decree of 23 February 2017, issued by the Ministry of Economy and Finance, was published in Official Gazette No. 56. The Ministerial Decree provides implementing rules on the CBCR obligation introduced to comply with BEPS Action 13, by Law No. 208 of 28 December 2015 (the Stability Law for 2016). But Italy goes beyond the OECD model legislation and doesn’t require an international agreement with the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction. If there is no competent authority agreement with the ultimate parent, that is enough to require local filing (IBFD 2017b, 10.2.2). |

| Jersey | Jersey domestic law goes beyond the OECD model legislation. If there is no international exchange of information agreement with the ultimate parent, the tax administration may require local filing (TAXATION (IMPLEMENTATION) (INTERNATIONAL TAX COMPLIANCE) (COUNTRY-BY-COUNTRY REPORTING: BEPS) (JERSEY) REGULATIONS 2016, Art. 6/b) |

| South Korea | Korea Tax Administration requires local filling of subsidiary “If it is not possible to exchange country-specific reports between the country where the parent company is located and Korea” (Google translate) thus goes beyond the OECD legislation. |

| Spain | Local filing of CBCR is required, including when no international agreement exists between Spain and the ultimate parent’s jurisdiction (Spain’s Tax authority new Model 231) |

| United Kingdom | Local filing of CBCR is required whenever the UK doesn’t have an international agreement that would allow it to receive the CBCR automatically from other countries (CBCR Regulations 2016, Art. 3.7.b) |

| Uruguay | Local filing will be required, whenever the CbCR cannot be effectively obtained via automatic exchange from other countries, according to Law 19484, Art. 67, that adds “Art. 46ter” to the consolidated text (Texto Ordenado) of 1996. |

Related articles

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

The State of Tax Justice 2025

Follow the money: Rethinking geographical risk assessment in money laundering

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

Bad Medicine: A Clear Prescription = tax transparency

Taxjustice would have much larger respect if it’d stop with childish phrases such as these

” The US president can opt to refuse to share his “confidential” tax return, while the income of any ordinary person in Sweden or Norway can be accessed by anyone. Perhaps ordinary Scandinavians are less afraid of being kidnapped than the US president, who’s protected by the Secret Service…”

Everyone knows what happens in a bathroom, yet I still lock the door when I take a shit.

Perhaps we ought to make it transparent?