John Christensen ■ Yes, Britain is closing its tax havens. But let’s not forget it created them in the first place

This post is jointly authored by Anthea Lawson and John Christensen

Tax justice campaigners celebrated this week as a nifty cross-party move from British Members of Parliament Margaret Hodge and Andrew Mitchell forced the UK’s Overseas Territories – many of them in the Caribbean – to stop hiding the owners of companies they incorporate.

The impact of the secretive company incorporation regime in the British Virgin Islands, one of the Overseas Territories, is well documented, not least in the Panama Papers, which could just as well have been called the BVI Papers since so many of the front companies were registered there. It fuels industrial-scale tax evasion and avoidance, corruption and crime, with consequences around the world, often for the poorest. The BVI had 417,000 companies last year – 18 for each inhabitant, and the Tax Justice Network estimates that this jurisdiction alone might be responsible for global tax losses of $37.5 billion.

It’s a massive shift that owners of such companies come into the light. We know this because we spent a long time arguing for it, John as a founder of the Tax Justice Network, and Anthea as the initiator of Global Witness’s campaign on secret company ownership. For a long time it was assumed, by everyone we spoke to in government or finance, that for companies to be able to hide their owners in secrecy jurisdictions was part of how business worked, and anyone who suggested otherwise was daft or ignorant.

John lost count of the number of times he was told that the UK wouldn’t do this in a month of Sundays. ‘If you were an economist, you’d know that what you’re saying isn’t possible,’ Anthea was admonished by one such economist. It is possible, and it is now happening. When Prime Minister David Cameron pledged that Britain would lead the way on public registries his promise extended to the Overseas Territories, which refused to cooperate, making imposition an inevitability. We should note that if the newly public registries are to serve a useful purpose as a deterrent to money laundering and corrupt practices, the quality of information will need massive upgrading and independent verification.

So yes, this should be celebrated. But let’s look at how we talk about it, and what hasn’t been said so loudly. The dynamic in play is that the UK has used its constitutional powers over the Overseas Territories to ‘force’ or ‘push’ them to implement public registers of company ownership, as indeed we asked it to do. It already sounds rather colonial, or, as the Caymans premier, Alden McLoughlin, was quick to note: ‘reminiscent of the worst injustices of a bygone era of colonial despotism.’

But that is precisely the point: the colonial meddling never stopped. The very fact that these jurisdictions have been operating as tax havens, with devastating consequences for the people of other nations, is because they were pushed to do so by Britain in the first place, not least to reduce aid dependence. Formal empire was ending and the City of London was desperate to keep other countries’ wealth flowing in as it had done for centuries. The Overseas Territories, as well as the Crown Dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man were quietly turned into a new spider’s web to funnel money towards the City.

So this is not a story about those bad secrecy jurisdictions that can no longer behave badly, and congratulations Britain for stopping them. It is right to stop this grubby business, but…

- not without acknowledging the extent to which these tax havens were created by Britain, that it has been in Britain’s interest to keep them running, and that the legal powers used this week have always been there but remained unused until campaigning pressure made that untenable.

- not without acknowledging the many trust and company service providers in Caribbean islands – the lawyers, notaries and clerks who do the legwork of setting up companies – who may go bust when their clients start sending incorporation business to Delaware or the Seychelles instead. Will the banks, Big Four accountancy firms and Magic Circle law firms who’ve done so much to create and maintain these secrecy centres now help compensate the local finance professionals who don’t have the option of decamping to another tax haven or back to London?

- not without acknowledging the ‘finance curse’ that has affected these islands in the decades since the UK helped turn them into tax havens, pushing out other forms of economic activity and committing them to a path dependency it will be hard to turn back from. What is the Plan B for these countries’ economies, and what is the UK going to do to help them get there?

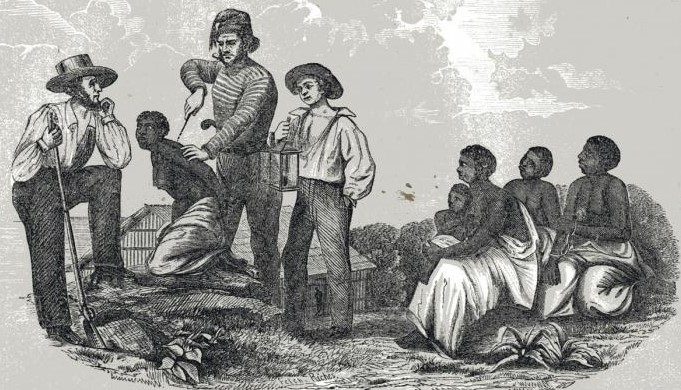

- not without acknowledging that some of the islands which will now be prevented from making a living as tax havens – as they had been encouraged to by Britain – are those populated largely by descendants of slaves, some of whom were abducted from their families and taken there by British ships. The history of abuse of these territories is long and filled with pain.

If the same transparency standards are not now imposed on Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man, as Margaret Hodge and Andrew Mitchell are saying they want to, then islands populated mostly by white people will be permitted to continue making a living extracting wealth from other countries, while those inhabited largely by black people will not. But there’s no reason why related legal powers couldn’t be used to make the same thing happen in the Crown Dependencies. The Supreme Court confirmed in 2014 that ‘the UK Parliament has power to legislate for the [Channel] Islands.’ It’s time it did.

If we talk about ‘clamping down’ on financial abuse in the Overseas Territories without acknowledging Britain’s role in creating it, we set off echoes that have direct relevance for some of those islands. It becomes another of those claims that takes credit for the stopping without talking about the starting – not unlike Britain’s claim to have ended the Atlantic slave trade, which gets repeated too often without acknowledgement of Britain’s role in creating and running that horror for so long.

So Britain has – finally – done the right thing. But it’s not the saviour here. This is just the first step in putting right a great wrong, and if it is not followed by financial assistance to help reorient the Overseas Territories’ economies, the wrong will be compounded once again.

Anthea Lawson is a campaigner and writer.

John Christensen is a founder, director, and chair of the Tax Justice Network, and former economic adviser to the government of Jersey.

Related articles

The Bitter Taste of Tax Dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss Swindle’

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

The State of Tax Justice 2025

Follow the money: Rethinking geographical risk assessment in money laundering

What a load of White supremacy, keep the niggers down, racist twaddle. Tax loopholes are created by badly worded tax laws not clever accountants. There is no compulsion to organise the affairs of a company, or an individual, so that the tax man can take out the largest possible portion of that bodies wealth.