George Turner ■ Questions raised over offshore dealings of Serbian PM’s former company.

The Croatian political magazine, Nacional, is running a story which implicates the International Finance Corporation in a deal involving offshore companies and more than a hint of a conflict of interest in Serbia. One of the main protagonists in the deal is the Serbian Prime Minister, Ana Brnabic.

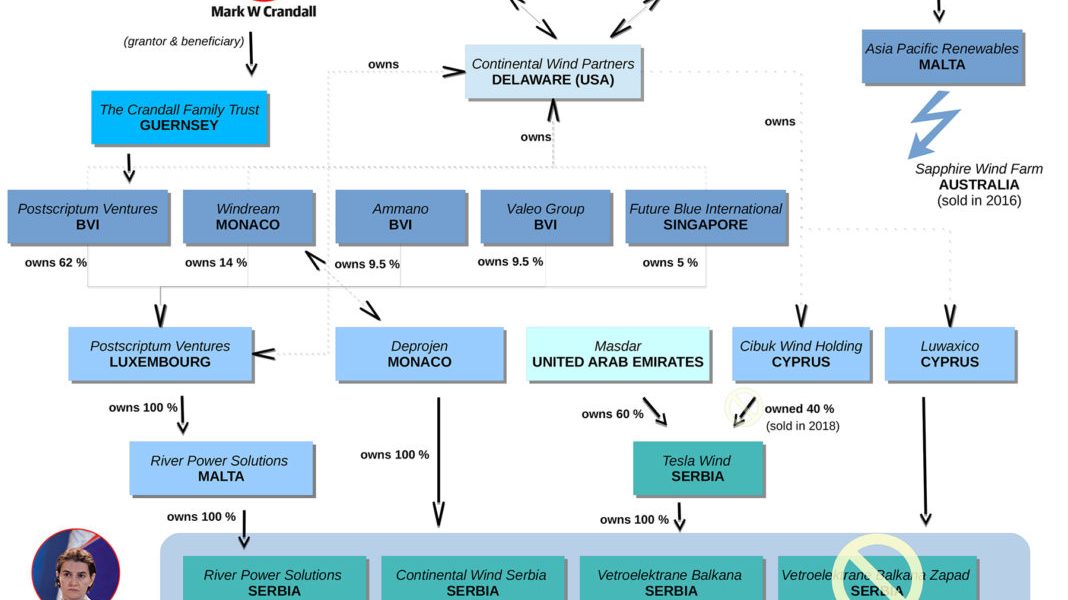

As with most offshore stories, the long and complicated twists and turns of the strings of offshore companies involve can be hard to follow but some facts emerge that at the very least highlight the severe deficiencies in the management of the international development finance sector in managing risk in their investments.

The basic story is as follows:

Prior to entering the Serbian Government, Ana Brnabic worked for an energy company that was investing in wind farms in Serbia, Continental Wind Serbia. Continental Wind had an exceptionally poor relationship with the Serbian Government. In 2015 the company was involved in a major scandal when the wife of its founder, Mark Crandall (one of the founders of Trafigura), was recorded in a phone conversation telling an opposition politician in Serbia that Continental had been asked to pay a bribe to the director of Serbia’s national energy distribution company in order to connect their wind farm to the grid. The man who was alleged to have requested the bribe was a close friend of the then Prime Minister of Serbia, Alexander Vucic.

Very shortly afterwards, Vucic visited Washington DC and a group of Congressmen organised a letter to Vice-President Joe Biden outlining allegations of corrupt practices in the country under his leadership. Vucic suggested that Continental was behind the letter, and wanted to use it as leverage to help win projects, saying: “Some want to build wind farms in Serbia where there was no proper regulation, with the idea of selling electricity at three times the market price…. They wished to win this deal at any cost”.

Brnabic, as the head of Continental in Serbia held a press conference denying that the company had been involved in any wrongdoing, stating that the bribery allegations were false. The scandal ended there.

Ten months later, in August, 2016 Brnabic was appointed by Vucic to be the Minister of Public Administration (taking over from the sister of Crandall’s wife). The following year she was surprisingly elected by the Serbian Parliament to become Prime Minister, when Vucic became President. During that time the relationship between Continental and the Government of Serbia had suddenly thawed. One affiliate of Continental won a 12 year contract to sell energy into the Serbian grid at a fixed price. Before the contract was signed the government amended its legislation to introduce greater price incentives for wind power.

This culminated in the launch of a major wind power project in 2017, funded by 190m Euro in loans from the International Finance Corporation and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The project launch was attended by Alexander Vucic himself.

Questions to answer

This kind of potential conflict of interest – political decisions being key to private returns, and individuals associated with private companies holding high political positions – should raise eyebrows. Add to this the fact that all of these investments were structured though highly murky offshore structures – involving shell companies and trusts in Malta, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Guernsey and Delaware. Structures that Ms Brnabic appears to have been, at the very least, aware of.

One might think, what on earth is the IFC doing getting involved in such a deal? As we have reported before, the IFC is all too comfortable with the use of tax havens to structure its investments. In this case a spokesperson for the IFC told Nacional:

“As with all projects funded by IFC, IFC undertook a thorough due diligence of the project, including the legitimate use of intermediary jurisdictions, to ensure that it meets all IFC investment criteria.”

The EBRD said:

“As with all projects funded by the EBRD, we undertook a thorough due diligence of the project, including the legitimate use of intermediary jurisdictions, to ensure that it meets all our investment criteria.”

Now there is no evidence that Ana Brnabic personally benefited from the deals between her former employer and the government, and she has said that she was not involved in any decisions made by the government of Serbia that concerned these investments by Continental.

Her statement to Nacional was as follows:

“I was not involved in creating the ownership structure outside of Serbia and I have no idea what it is… I have reported to the Anti-Corruption Agency that I was the CWS Director and that I do not want to have any influence on any decisions that generally concern the policy of renewable sources in Serbia. As the Minister of Public Administration and Local Self-Government, I absolutely was not involved or had no contact points with the legislation concerning renewable energy sources…. I was not personally involved in drafting and accepting regulation on state incentives as I was not in the Government at the time….

All taxes were paid to the Republic of Serbia and we always tried to be a socially responsible company, as best confirmed by numerous donations and contracts with local government that part of the company’s profit is paid directly to the budget of the municipalities.”

But isn’t the real issue this: Large scale infrastructure projects rely on key government decisions in order to be viable, at which point the owner is granted stable, often taxpayer-funded, long term profits. In this particular case the benefits appear to have been particularly generous. In a world where people move between the public and private sector frequently, and particularly in smaller economies where the pool of people working at the top of government and in business is small, there exists the potential for huge conflicts of interest.

Policy responses

In this context there needs to be a much greater obligation placed on these companies to be transparent. It is not good enough for the IFC and EBRD to simply say ‘we looked at it, and trust us, it’s all fine’.

Large international financial institutions should use the market power they have to drive out financial secrecy, not to acquiesce with it – otherwise the kinds of scandals being reported in Serbia today will only continue.

At the national level, there is a full policy agenda. Alex Cobham, chief executive of Tax Justice Network, told Nacional that this deeply worrying story of financial secrecy and the mingling of public and private interests confirms the importance of key transparency policies, in order to protect the public from the risks of corruption and tax abuse.

“First, it is crucial that we have public registers of the ultimate beneficial ownership of companies and of trusts and foundations. Such a measure, now required in the EU through the revised Anti Money Laundering Directive, is the new international standard. Relatedly, governments should only allow companies to do business in their countries if they publish their true ownership and their accounts. At the same time, politicians and senior civil servants must be required to declare publicly their assets to guard against conflicts of interest.

“Secondly, this case makes clear that all public contracts must be in the public domain. There can be no good reason to prevent the public seeing how their own money is being spent by their elected representatives – and that logic extends equally to subsidies and tax incentives. The importance of incentives for the global switch to renewable energy makes this an industry of particular concern, likely to attract unscrupulous operators with no interest in sustainable development,” Cobham said.

“Finally, this story highlights the shocking failures of the World Bank’s IFC, and of the EBRD. These are institutions that claim to invest for the public good, but consistently refuse to ensure financial transparency or appropriate tax behaviour of their projects – and so once again find themselves associated with risks of corruption and tax abuse. Their policy choice to accept financial secrecy regardless of the public harm is shameful,” he added.

Related articles

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025