Alex Cobham ■ Panama Papers: Who were the big players?

The Panama Papers revealed a systemic challenge to global governance, in which the big players are major banks, multinationals and the biggest financial centres of all. Unsurprisingly, much of the coverage of the Panama Papers focused on juicy, individual stories: political conflicts of interest, criminal money laundering and HNWI tax evasion in exotic locations. But when you look at all the data, you see a different picture.

With a few friends of TJN, we’ve been running some of the numbers on Panama, to see just where this small jurisdiction fits in the global game. The picture is inevitably partial – a leak from Jersey or Delaware would show other angles. But what is revealed is a clear snapshot of one part of the systemic business making use of secrecy. Not necessarily for corrupt purposes… but when your business is not engaged in some sort of unsavoury activity, you don’t need secrecy, so the use of secrecy is a pretty good red flag for further investigation.

The banks and their country backers

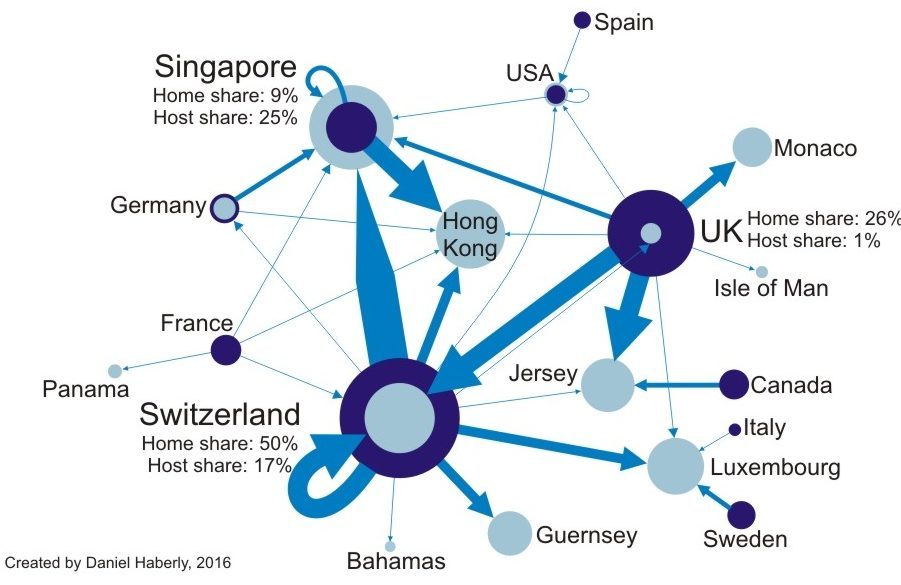

First, we asked Daniel Haberly, an economic geographer at the University of Sussex, to look at the role of banks in the database from the Panama Papers, which includes the earlier Offshore Leaks data that relates to a network of company formation agents primarily in the British Virgin Islands. The analysis looks at the home country of banks that act as intermediaries to set up anonymous companies, and the host country role – where local affiliates of banks (from anywhere) are the intermediaries.

The graphic (click for full size) shows clearly that Switzerland is the biggest player, being home to banks that account for half of all the entities looked at; and also one of the leading host economies for intermediary banks. The UK is home to more than a quarter of the bank intermediary activity, but hosts very little; while Singapore shows a reverse picture, hosting a quarter but being home to less than 10%. As suggested in earlier analysis, the US role here is relatively small – with so many of its own states providing anonymous company formation.

Bilateral relationships are also revealed, sometimes less predictable than others. For example, Jersey’s disproportionately large role is due to business from UK banks; while its fellow Channel Island of Guernsey, in contrast, is largely reliant on business from Swiss banks. German banks support activity in Hong Kong and above all Singapore.

Of course the data is for one law firm over 40 years and one network of company formation agents up to around 2010, so may not be a great guide to current business models. But what it does show is that the role of individual clients, or of particular small jurisdictions, is almost incidental: the structural driver of the secrecy business has been the global banks, and the rich countries that they call home. Responsibility for offshore entity banking is not evenly distributed throughout the rich world, however, but rather seems to be heavily concentrated in Switzerland and the UK, whose banks have a combined 76% market share for this particular dataset. The scale of activity by British banks also underscores that even though a jurisdiction may curtail offshore banking activities at home, its banks may nevertheless be leading players in these activities overseas.

The strong third-place position of Singaporean banks as offshore entity intermediaries, together with Singapore’s first place ranking as a host jurisdiction within which foreign banks operate, also lends credence to arguments that increased international pressure on traditional wealth management centres such as Switzerland may be displacing activity to up-and-coming centres in Asia. This underscores the need for a global approach to transparency – as of course does the rise of the US as a tax haven of choice for many.

The multinationals

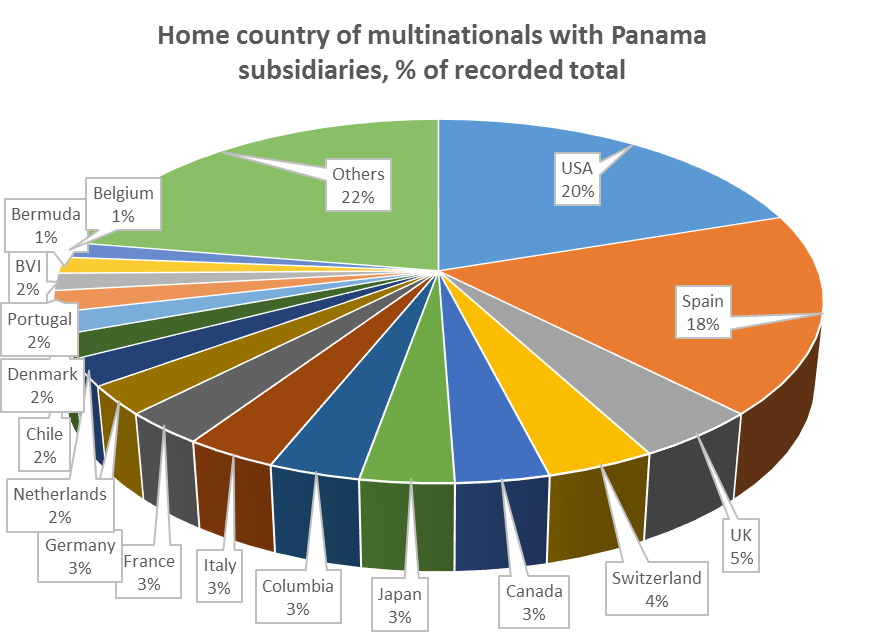

Taking a wider lens, economist Yama Temouri of Aston Business School used ORBIS, the biggest global database of corporate balance sheets, to look at the sort of multinationals that have subsidiaries in Panama. Two countries which feature relatively little in the Panama Papers are seen now as prominent: multinationals based in the USA and Spain are responsible for around a fifth each of all the recorded Panama subsidiaries, with the UK and Switzerland following behind with less than a tenth between them.

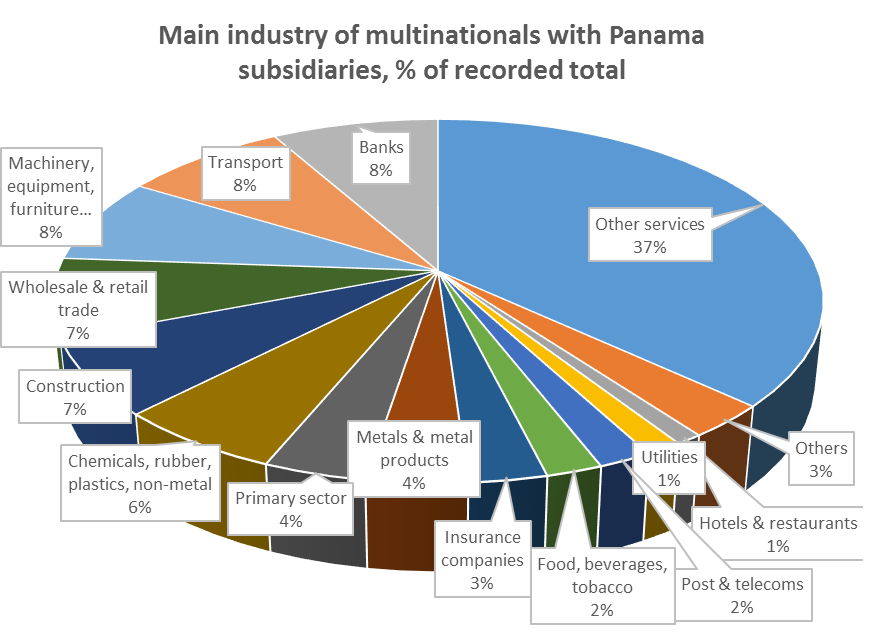

The analysis also shows that while banks are important players in Panama, confirming the findings above, the use of this secrecy jurisdiction is common to all the major industry sectors. ‘Other services’ including is by far the biggest category, and taken together with banking and insurance makes up around half of all Panama subsidiaries – but beyond that, the full range from construction to telecoms, and from machinery to tobacco, is represented.

Of course we’re not claiming for a moment that all the multinationals using Panama entities are aggressively avoiding tax, nor that they are committing any crimes. But the alarm bells should ring when such entities are seen: why would global businesses set up in jurisdictions that combine such limited real economic activity and such powerful secrecy characteristics, if not for the purpose of hiding things from regulators and/or tax authorities elsewhere?

[We’ve been having a comical non-exchange with Monsanto, in which despite numerous requests through various channels, the agri group refused to provide even a ‘no comment’ to the question of whether or not a particular Panama-registered company with that name is or was part of their structure. We were interested in part because the entity in question is claimed to have a director who died many years ago. Which wouldn’t suggest very high standards of governance…]

Even this quick run through the data makes clear the systemic involvement of banks and multinationals in the global secrecy business. Central too, rather than helpless victims or innocent bystanders, are the rich countries and their dependencies which run the game. And we shouldn’t forget the big 4 accounting firms (on whose association with tax haven use, Yama Temouri’s paper has incidentally won an award).

The locus of corruption

Finally, the Panama Papers confirm – for anyone who still needed this to be confirmed – that corruption is not a poor country problem. It might be closer to the mark to say instead that corruption has long been a rich country way of doing business. What is exciting now is that this is increasingly understood, by policymakers and public alike. The Panama Papers have made concrete for many what was already felt: that financial secrecy offers impunity and an escape from laws and taxation, for elites at least.

Analysis of the data by Matt Collin, a research fellow with the Center for Global Development, confirms this. Matt concludes that the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index, our ranking of ‘tax havens’, is:

“one of the most reliable predictors of a country’s dealings with Mossack Fonseca… A 10% increase in a country’s FSI is associated with an approximately equivalent increase in the number of entities from that country named in the Panama Papers. A one standard deviation increase in the FSI – roughly equivalent to moving from Norway to Jersey – leads to about a 90% increase in the number of entities. Other measures carry less predictive power”.

The challenge ahead

So, one year on from the Panama Papers what have we learned about how the offshore world uses secrecy?

Responsibility for offshore entity banking is not evenly distributed throughout the rich world, but seems to be heavily concentrated in Switzerland and the UK, whose banks have a combined 75% market share for this particular dataset. The scale of activity by British banks also underscores that even though a jurisdiction may curtail offshore banking activities at home, its banks nevertheless appear to be leading players in these activities overseas.

The Panama Papers are a snapshot of the major banks and leading financial centres, that have made a business for decades from the provision and exploitation of secrecy structures; with major multinationals high up on the client list. (And we haven’t mentioned the frequency with which big 4 accounting firms appear in the data – that can be for another day. Everything from billion-pound property transactions to the flightiest of fly-by-night, blink-and-they’re-dissolved operations…) The forces invested in the current system, and so allied against change, include some of the most powerful private sector actors in the world – and by extension, many of the jurisdictions in which they operate.

A year on, we still need a step change in international financial transparency as a necessary precursor to global progress against impunity and tax injustice. While policymakers increasingly pay lip service to the specific measures needed, real progress remains painfully slow.

Related articles

UN tax convention hub – updates & resources

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The bitter taste of tax dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

Taxing windfall profits in the energy sector

14 January 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)

Thanks to those who have been doing this work – we all need to know about it!