Nick Shaxson ■ Will the OECD tax haven blacklist be another whitewash?

Finance Ministers from the G20 countries meet in China on July 23-24 – this weekend. Amid sessions that will focus heavily on Brexit-related issues, there will be an important tax component. At their previous meeting they mandated the OECD to “establish objective criteria . . . to identify non-cooperative jurisdictions with respect to tax transparency.”

Finance Ministers from the G20 countries meet in China on July 23-24 – this weekend. Amid sessions that will focus heavily on Brexit-related issues, there will be an important tax component. At their previous meeting they mandated the OECD to “establish objective criteria . . . to identify non-cooperative jurisdictions with respect to tax transparency.”

A blacklist, in other words.

We recently wrote about how not to create blacklists, focusing on European Union efforts to draw them up. Now it’s the OECD’s turn to produce a blacklist.

The OECD has a long and very patchy record of mis-identifying tax havens: usually the criteria are tweaked, and funny exceptions made, and the end result is that mostly only small, weak islands make the list while the giants in the game – the United States, Britain, not to mention the more traditional places like Switzerland and Luxembourg – somehow manage to skip free. (See this TJN-written article in the Financial Times on that sorry spectacle, or a more in-depth analysis here.)

From what we can see, it looks like the same game is being played now, with particular attention being paid to letting Tax Haven USA off the hook.

Now the OECD has just told us their methods: how they intend to go about identifying recalcitrant jurisdictions this time. (The European Union is also in the process of drawing up its own blacklist, and it is likely to follow the OECD’s lead on these criteria.)

An OECD webinar looks at the criteria – that section starts after about 36:00 minutes. In summary, the criteria are:

- If the country gets a rating of “largely compliant” or better from the OECD’s Global Forum, as regards the “exchange of information on request” standard of transparency. This is an old, not very useful standard of bilateral country-to-country information exchange, which still has its uses, but which has been overtaken in importance by the OECD’s new Common Reporting Standard (CRS), a far more powerful system of automatic (and largely multilateral) information exchange.

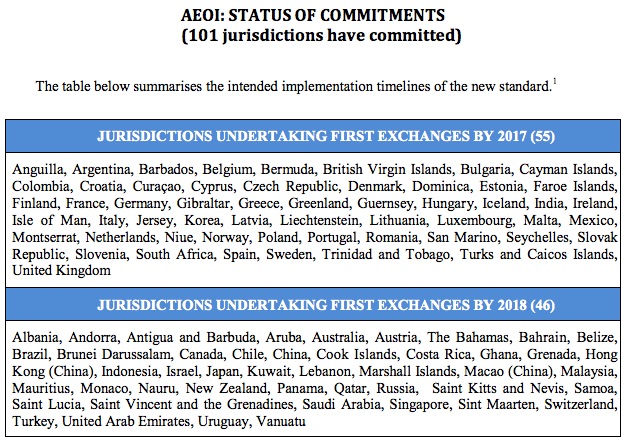

- The country commits to adopting CRS, and to begin exchanges by 2018 at the latest.

- The country has signed the “Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (MCMAA),” a much older, multilateral framework for all kinds of information exchange, or if it has what the OECD considers a sufficiently broad exchange network providing for exchange of information on request and automatic exchange of information. (Forgive the confusing acronyms, but don’t mix the MCMAA with the MCAA, which is the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement on Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information which supports the CRS mentioned in criterion 2.)

Now, let’s see.

How to get off the blacklist, in baby steps

The first and most glaring escape route from the blacklist is that a country only needs to fulfil two out of these three criteria! (There’s a complication here: see the Endnote.) So a country can implement the fairly useless ‘on request’ standard, plus the MCMAA, yet shun the OECD’s much more comprehensive flagship CRS project – and skip free of blacklisting. Even the European Union’s fairly feeble blacklist project will likely require all three: see below.

Not only that, but a jurisdiction could ‘commit’ to participating in the CRS, and then delay or obfuscate or put into place all sorts of conditions, as Bahamas and several other jurisdictions are doing. Or they could sign the MCMAA but not yet ratify it or put it into effect. (Germany, for example, signed it in 2008 but didn’t ratify until last year.)

So this is already very weak medicine. But there’s plenty more. Even if we look only at Criterion 1, there are a bunch of questions.

- Why only ‘largely compliant’? The standards are so incredibly weak anyway: why not just ‘compliant.’

How is it that the US acknowledges, among other things, that (for example) with its single-member LLCs that don’t produce US-sourced income, there may be no ownership information whatsoever — and yet the Global Forum deems the US “largely compliant”? (see more on our Loophole USA blog, and associated updates.)

- Germany allows bearer share companies! These are some of the most pernicious secrecy facilities ever: perfect for criminals. And yet Germany’s company ownership is rated largely compliant – though Switzerland’s bearer shares are rated as non-compliant. Is this unequal treatment because Germany is more politically powerful than Switzerland? The OECD must explain.

Now let’s look at Criterion 2 – whether or not countries are participating properly in the all-important CRS. Well, the big one here is Tax Haven USA. See our Loophole USA blog, and the associated updates, for more on the problems. It isn’t on this list as of May 2016.

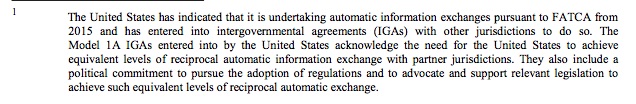

The footnote to this table, though, indicates it has a funny status:

And in this list from February, it’s also described in a footnote on p21 as having the same funny status. If the past is any guide, ‘funny status’ is usually a route to a fudge that allows a player to escape the blacklist. (And there are many players outside the U.S. who love the idea of Tax Haven USA, and are actively supporting and exploiting the idea.)

Inclusion of the USA on any eventual blacklist will be a litmus test of its credibility.

Not only that, but we are hearing loud and clear, behind the scenes, of another jurisdiction that is being especially aggressive at the moment in promising to hold on to secrecy – the Bahamas. More on that poachers’ den in a subsequent post, but for now we’d suggest that any blacklist worth its salt will have Bahamas on it. The above table contains the Bahamas – so it is en route to a whitewash.

There’s also another question with respect to the United States and Criterion 3 here.

A number of countries have signed but not ratified the amended MCMAA – as of February 2016 (p.28, here), that is, Andorra, Barbados, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, El Salvador, Gabon, Guatemala, Israel, Kenya, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Morocco, Niue, Philippines, Senegal, Switzerland, Turkey, Uganda, United States. Note that the United States is listed here. Although the US has ratified the original Convention, it has signed but not ratified the Amending Protocol – meaning that the US will only provide data to OECD members. Once again, it’s a funny status.

And why is the OECD demanding only signature, and not ratification and effective implementation of the (amended) convention? This makes no sense at all, beyond trying to find ways to exempt certain powerful countries.

A far better approach is to create lists based on objectively verifiable criteria, like the FSI, and not allow funny exceptions.

The silver lining in here is that developing countries that do not have financial centres will not be considered non-cooperative and placed on the blacklist. They don’t have the capacity to implement this stuff, and nobody’s using them as tax havens anyway. However, we don’t yet know how the OECD will define developing countries. If they’re not careful they risk omitting serious offenders like Vanuatu, Liberia and Gambia which are aggressively pushing to attract financial business with mucky secrecy practices. And if they only go for the very poorest countries, they will require some still quite poor countries (like Nigeria) to invest great efforts in playing ball, even though nobody in their right mind would stash their money in these places.

The EU blacklist project

The EU is also putting together its own blacklist project with its own criteria. These are, as we’ve mentioned, likely to be stiffer than the OECD’s – but they will be heavily influenced by it, and they might come under OECD attack if they do show some courage. And what we know so far of the EU project is that it is likely to contain worrying holes. For example, they are expected to automatically exempt any EU member state and the associated tax havens of Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Andorra, Monaco and San Marino. To let Luxembourg off the hook, once again, is unconscionable.

The EU, however, currently plans to insist on all three criteria being fulfilled – this is likely to be a major point of contention with the OECD, along with an expected requirement for ratification, not just signature. The prospect of Tax Haven USA being identified may not go down too well in Washington. Not only that, but the EU currently seems to want to bring in a tax element: a zero corporate tax rate criterion. This is also welcome although in our view it would be far better to focus on effective tax rates, not headline tax rates, and to focus on a number that’s far above zero.

How to make the OECD tax haven list better

We have already written plenty of times how TJN’s Financial Secrecy Index (FSI) offers a better alternative to politically-drawn tax haven lists. Not only is the FSI objective (every ranking and assessment can be tracked down to its legal source and explanation), but it is the only global analysis on tax havens that points fingers at the OECD countries’ secrecy provisions (that not surprisingly, the OECD minimizes or ignores, as shown above).

Even if the OECD disregarded the FSI, their 2nd and 3rd criteria could be enhanced by requiring that, instead of simply “committing to implement the CRS by 2018” and “sign the MCMAA”, countries should:

- Ratify the Amended MCMAA (criterion 3, which is one pre-requisite to implement the CRS), and

- Sign the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement (MCAA), which is the other pre-requisite to have the CRS in place. After signing the MCAA, countries may choose, among other cosignatories, with whom to exchange information. It thus works as a ‘dating system’, because like ‘Tinder’ app, automatic exchange of information will only take place among countries that were matched together. That is why an extra requisite should be to “choose every other cosignatory of the MCAA in Annex E” (the ‘dating system’).

Otherwise, if country A, say Bahamas, only exchanges information automatically with country B, Cayman Islands, it would still be considered a kosher jurisdiction implementing the CRS (and not a tax haven). Even worse, until 2018, any jurisdiction could simply declare that they “commit to the CRS by 2018”, while not ratifying or signing the MCAA, and still be considered as meeting criteria 2 and 3.

Endnote: It isn’t necessarily deemed enough to fufil two of three criteria. If a jurisdiction is determined by the Global Forum to be “non-compliant”, or is blocked from moving past “Phase 1”, or where it was previously blocked from moving past Phase 1 and has not yet received an overall rating under the Phase 2 process, it will be considered a non-cooperative jurisdiction, even it it has met the benchmarks of two of the three criteria. As of February, the blacklist comprised the financial giants of the Federated States of Micronesia, Guatemala, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Liberia, Nauru, Trinidad and Tobago, and Vanuatu.

Related articles

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

Follow the money: Rethinking geographical risk assessment in money laundering

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Vulnerabilities to illicit financial flows: complementing national risk assessments