Alex Cobham ■ How the OECD had a ‘bad Panama Papers’ – and why it matters

This is a long read, with three main components. First, we examine the OECD’s position as an international tax organisation – and the gradual weakening of its preeminence. Second, we consider two specific aspects of the OECD’s work as a watchdog for noncooperative jurisdictions, as they have played out in the Panama papers. And finally, we draw some conclusions about the scope for an intergovernmental tax body (but more directly about the importance of using objectively verifiable criteria for any ‘tax haven’ blacklisting that might follow Panamania.

After a lot of argument and evidence we will draw some quite strong conclusions, such as this one:

“The OECD is unable, politically, to identify the fastest growing financial secrecy jurisdiction as non-cooperative. There is then no basis on which the OECD could be considered as a legitimate, international arbiter of global tax cooperation. It is all too clear that the OECD is unable to be consistent in its analysis of different jurisdictions.”

1. The OECD: A good crisis?

By common consensus, the OECD has had a good financial crisis. The G8 and G20 have made it the global leader on tax issues. Ongoing austerity has stiffened political will, allowing some real progress to be made.

The Panama Papers, too, have provided the OECD more time in the spotlight. Senior figures have been widely quoted in the media, highlighting Panama’s non-cooperation with their processes, in order to bolster their credibility.

But there have been suggestions that the tide is turning among global policymakers. And a closer look at Panama’s treatment, pre- and post-leak, raises serious questions about the OECD’s suitability to lead. As we set out below, the OECD’s position reveals two serious flaws.

- First, the OECD has flip-flopped almost completely on their portrayal of Panama since the leaks. The inconsistency reveals a deeper weakness in the organisation’s ability to provide global leadership on matters of substance.

- Second, even the post-leaks position is shown to be completely at odds with the facts – in a way that confirms the OECD is unable to act as an honest broker where its own members are concerned.

The time may have come to establish an intergovernmental tax body that is fit for purpose.

A turning tide?

Three pieces of evidence support the view that things are shifting.

Development debate.

First, the debate around tax issues in the Sustainable Development Goals has laid bare the antagonism towards the OECD. The first half of 2015 was dominated by developing countries’ fight for a globally representative, intergovernmental tax body to be agreed as a key outcome of the Financing for Development summit held in Addis in July.

While unsuccessful in that context, the G77 and their broad civil society support were able to maintain the question of OECD legitimacy at the top of the agenda throughout the process, and beyond. If anything, the defeat of the G77 grouping – due to intense US and UK lobbying in particular – has strengthened the sense that the OECD is not capable of becoming more than the club of rich countries.

BEPS.

The OECD’s handling of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative to tackle corporate tax cheating, at the behest of the G8 and G20, is increasingly seen to have delivered little real change in terms of multinationals’ tax avoidance. This is especially true for developing countries, where rule changes have yet to show obvious benefits.

Perhaps more importantly, access to companies’ country-by-country reporting will not be automatic but will depend on the data being passed on by tax authorities in the headquarters countries – largely OECD member states. This hinges on meeting certain conditions, so that the data cannot be made public, nor used for unitary tax approaches – regardless of, or perhaps because of, the fact that such approaches might well reduce avoidance markedly.

Institutional politics.

Finally, other institutions – notably the IMF, but also the World Bank and UN organisations – have taken advantage of the development discontent with the OECD to promote their own claims. The IMF has continued to publish research suggesting not only that OECD estimates of profit-shifting are far too low, but also that the true scale of the problem is relatively larger in non-OECD countries.

The G20 has mandated a ‘platform’ made up of all these organisation, to ensure greater progress in a range of tax-related areas. The launch, later today, is likely to be underwhelming since each organisation will seek to maintain independence. Over time, however, it is not impossible that a forum emerges in which development issues take precedence over OECD, or OECD member, priorities. At the least, the pre-eminence on tax issues of the OECD has taken something of a hit, and the platform’s agenda is likely to go beyond the organisation’s comfort zone.

2. Panama Papering over the OECD’s cracks

The immediate opening up of the Panama papers saw the OECD hit the media trail, making a clear claim: Panama is the last, dirtiest, secrecy jurisdiction.

“Panama has an extremely aggressive and obstructive attitude. Dialogue has broken down,” said Pascal Saint-Amans, the OECD’s tax chief. “It is the last financial centre that has refused to implement global standards of fiscal transparency. There has been very strong pressure from the law firms on the Panamanian government.”

Mr Saint-Amans said offshore secrecy in on the wane in most of the world, but becoming more concentrated in Panama. “The majority of undeclared clients are coming clean in other locations, but those who don’t are going to Panama,” he said.

Consistency of OECD’s treatment of Panama

W e need to make two checks on this. First, is it consistent with the OECD’s treatment of Panama before it was known these explosive leaks were on the way? That is, did the OECD provide a genuine assessment – or did it tailor its position for public consumption once it knew the leak was coming?

e need to make two checks on this. First, is it consistent with the OECD’s treatment of Panama before it was known these explosive leaks were on the way? That is, did the OECD provide a genuine assessment – or did it tailor its position for public consumption once it knew the leak was coming?

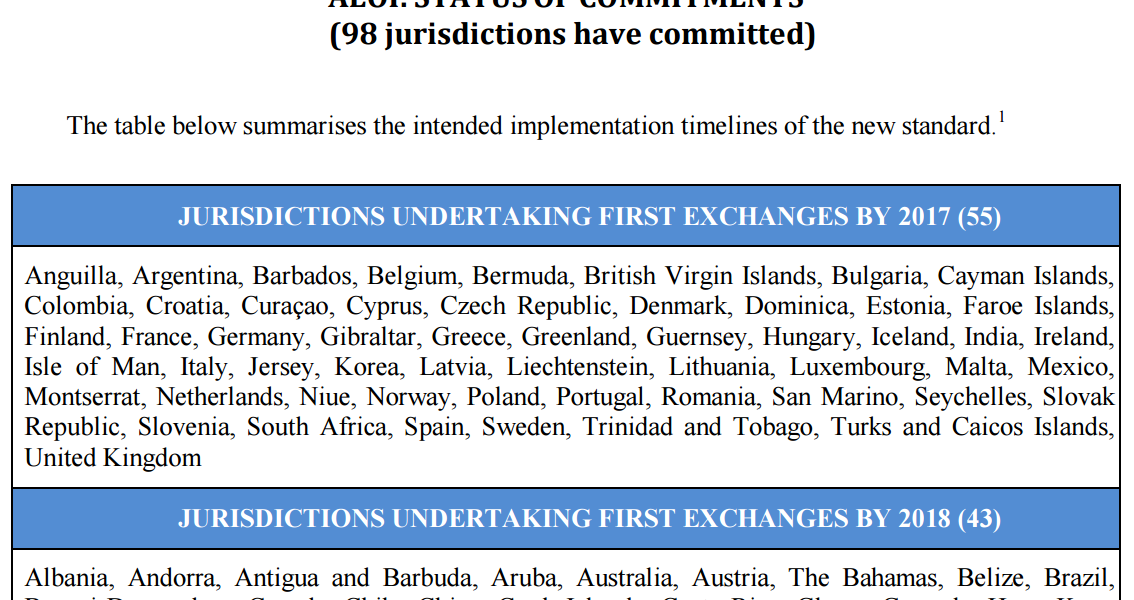

The most recent summary of cooperation with the global standard is from 14 April 2016, a little over a week after the leaks broke. The position is clear: out of 98 jurisdictions, Panama, along with just one other, is well and truly on the naughty step.

The wonders of the worldwide web archive allow us to look back in time, however. The previous version of the summary available is dated 11 December 2015, and was archived on 29 January 2016.

And here we find that Panama had actually made it off the naughty step, instead being included along with 40 others – the likes of Australia and er Switzerland – as committed to international information exchange from 2018.

Looking further, it turns out that Panama had been assessed favourably by the OECD Global Forum in Phase 1 (of two phases of assessment for exchange of information). An abridged assessment table allows comparison of Panama with Albania (arbitrarily, the first listed phase 1 assessment) and also Nauru and Vanuatu. The latter two have been accepted by the OECD, as at April 2016, as committed to information exchange from 2018. Panama, which clearly scores far better, was kicked off this list – despite passing its Phase 1 assessment while Nauru and Vanuatu failed by a wide margin.

What happened to Panama? Why was the successful phase 1 review, and commitment to 2018 info exchange, apparently set aside between 14 March 2016 and 14 April 2016?

Here’s the story, as best we can put it together.

On the question of commitment to exchange information, the Global Forum decided to ask Panama in February 2016 if it had really meant what it said in October 2015, that it would exchange from 2018. Panama said no, and there you have it. At the G20 this week, OECD head Angel Gurria delivered a report stating as follows:

With respect to AEOI, Panama, as a significant financial centre, is expected to commit to implement the AEOI standard (the Common Reporting Standard) and begin exchanges by 2017 or 2018. After the Global Forum sought confirmation of the commitment to the CRS given by Panama in October 2015 before and at the Global Forum plenary meeting, in February 2016 Panama advised that it was not in fact committed to the AEOI standard. I advised this to you in my report for your Shanghai meeting.

The Shanghai meeting was held 27 February – here’s Gurria’s speech delivered there (no mention of Panama, so presumably the advice is contained in documents elsewhere).

It’s not clear whether the Global Forum would normally check such a position every few months, in light of a commitment several years away; but in this case, at least, they did. Had the OECD heard of the leaks by then? Many had, but we don’t know.

The Global Forum assessment will continue: the “Phase 2 review was launched in December, and the report, focused on Panama’s practical implementation of the EOIR standard as well as its efforts to meet the outstanding Phase 1 recommendations, is expected to be published by late October 2016.” Given how far Panama was ahead of other former naughty step jurisdictions in the Phase 1 assessment, what can be expected? How much useful information do the assessments actually provide? Could Panama sail through phase 2 while remaining entirely uncooperative?

Most importantly: Given what the Panama papers have revealed, which has nothing to do with any commitment or otherwise for 2018, could any reasonable assessment have found it ready for information exchange? We don’t think so – that’s why Panama ranked 13 in the (November 2015) Financial Secrecy Index, despite its small size.

Its secrecy score of 72 out of 100 puts it in the highest group. At most, only 7% of global financial services provided to non-residents go through more secretive jurisdictions than Panama; and less than 1.5% if we set aside Switzerland, with its near-identical secrecy score of 73.

Our assessment concluded:

Overall, Panama remains a jurisdiction of extreme concern for TJN.

Consistency of OECD’s wider approach

The second question to consider is whether the OECD assessment approach, Panama aside, is consistent – or indeed fair and reasonable. We have already highlighted the OECD’s apparent inability to note publicly the non-cooperation of its biggest member, the US.

There is a little bit more to this story, however. To go back to the beginning, it was the Obama administration’s Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, requiring automatic information about US citizens from all financial institutions globally, on pain of 30% withholding tax, that finally broke the back of Swiss (and others’) resistance.

Now the Tax Justice Network had pushed automatic information exchange from the early days of our establishment in 2003, despite the OECD’s longstanding position that (non-functioning) information exchange ‘on request’ was the international standard; so we welcomed warmly the swing that followed FATCA, with the OECD being mandated to produce the Common Reporting Standard which requires automatic exchange.

In May 2014, the US was one of 48 signatories to a commitment to introduce the standard on a common, multilateral basis. The declaration stated their determination “to implement the new single global standard swiftly, on a reciprocal basis. We will translate the standard into domestic law, including to ensure that information on beneficial ownership of legal persons and arrangements is effectively collected and exchanged in accordance with the standard.”

By October 2014, however, the United States had U-turned – rejecting the standard outright, despite its own pivotal role in the standard’s emergence. Instead, a form of words was adopted which has been maintained ever since, in a footnote on each OECD update on coooperation:

The United States has indicated that it will be undertaking automatic information exchanges pursuant to FATCA from 2015 and has entered into intergovernmental agreements (IGAs) with other jurisdictions to do so. The Model 1A IGAs entered into by the United States acknowledge the need for the United States to achieve equivalent levels of reciprocal automatic information exchange with partner jurisdictions. They also include a political commitment to pursue the adoption of regulations and to advocate and support relevant legislation to achieve such equivalent levels of reciprocal automatic exchange.

Two main points are made here, and as they are not necessarily obvious, it is worth pulling them out:

- The US reverses its support for the multilateral, automatic exchange of information.

- The US reverses its commitment to ensure that beneficial ownership information is collected.

Note that the new commitment is to ‘pursue’, to ‘advocate’ for and to ‘support’ progress – not to deliver it. The same language has featured around beneficial ownership information in every US National Action Plan, and represents the position that the administration will not require states – which compete to offer anonymous company services – to conform to international standards.

This dramatic reversal is the reason the US has been the only major secrecy jurisdiction to move up the Financial Secrecy Index, leapfrogging Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands to go from 5th place to 3rd place in 2015, spawning international coverage of ‘Tax Haven USA‘.

The OECD has refused to include the US under its category of non-cooperative jurisdictions, which have been labelled since 2014 as: “JURISDICTIONS THAT HAVE NOT INDICATED A TIMELINE OR THAT HAVE NOT YET COMMITTED”. It is only possible to imagine that the US is excluded on the grounds that it has indicated a timeline, i.e. never.

In the OECD’s G20 document just published, however, there is a change of language. Here the label is “JURISDICTIONS THAT WERE ASKED TO COMMIT TO A TIMETABLE BUT THAT HAVE NOT YET DONE SO” – opening the way perhaps to exclude the US as never having been asked?

Surely not – but you wouldn’t be entirely surprised, given the ludicrous starting point of pretending that the US isn’t non-cooperative. As you’d imagine, we and others have poked fun at this. But there is an absolutely serious point here.

The OECD is unable, politically, to identify the fastest growing financial secrecy jurisdiction as non-cooperative. There is then no basis on which the OECD could be considered as a legitimate, international arbiter of global tax cooperation. It is all too clear that the OECD is unable to be consistent in its analysis of different jurisdictions.

3. The importance of ‘tax haven’ criteria

Two things follow. First, it seems increasingly unlikely that the OECD’s credibility as an international arbiter can survive the growing recognition – by everyone else – of the non-cooperation of Tax Haven USA. Assuming that the organisation simply cannot cross that line, this is a compelling argument for an intergovernmental tax body that is broadly, globally representative.

The second point is that, notwithstanding the OECD’s attempt to defy its own criteria, this episode actually proves the value of objectively verifiable criteria, rather than criteria that are subject to political manoeuvrings, fears, intimidation or whimsy. The OECD’s criteria of signing up to the CRS are shown as weak – actual delivery is necessary before pass marks can be handed out. Panama’s performance on the phase 1 assessment, meanwhile, suggests the need for a serious rethink.

At the same time, the whole episode (and yes, we would say this) does rather lend support to the Financial Secrecy Index in which Panama was identified ex ante as of extreme concern – the joy of having objectively verifiable criteria, and sticking to them.

That leads us to the last point. There has been much talk since the Panama Papers broke of a new blacklist. UK Chancellor George Osborne called for

“an international blacklist of tax havens [with sanctions]… all the countries of the OECD would accept that this was a list that would trigger certain consequences like withholding taxes.”

The academic analysis that underpins the Financial Secrecy Index shows clearly the impossibility of drawing a hard line between ‘tax havens’ and others, reflecting that every place is offshore for everywhere else and that there is a spectrum of financial secrecy which determines the damage – rather than a binary distinction between secretive and transparent jurisdictions.

Nonetheless, specific secrecy behaviour could be made the objectively verifiable criteria for a list of jurisdictions to be the target of specific countermeasures. The emerging norms would suggest criteria of refusing to make public the beneficial ownership of companies, trusts and foundations; and/or refusing to provide such information automatically on a multilateral basis, including to developing countries.

The suggested countermeasure of imposing withholding taxes is one that we have proposed and promoted already – making the crucial point that any reasonable criteria will bring the US into scope, and therefore that the EU must be prepared to take that stand if is to carry weight. Would the EU step up? As it seems the OECD’s hands are tied, that may be the only option.

Related articles

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

An insightful assessment that reveals the inadequacy of current Global institutions. Most commentators seem to favour a process of slow evolution: combining interested groups of NGOs, enlightened World leaders, United Nations bodies and other non-state actors over time, but the forces at work to prevent change are simply too great. At the heart of this lack of Global authority lies the resistance of the USA to make itself subject to any external authority. The biggest shock is not that “Tax Haven USA” is non-cooperative, but that the OECD is prepared to completely overlook this in it’s reports.

This is why I recommend establishing a new “Global Economic Community” starting from a core of G20 nations. The international stakes are of course very high, but every country would ultimately benefit from a body which could for the first time create a regulated single market with access to 85% of World GDP. This prize is big enough to incentivise even the USA not to be left out of such a club. Most people will regard this as wishful thinking, but it is very hard to see any other route to change. As Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever comments “The Global Race” reminds us that at the heart of our problems lies a crisis of Global governance. In reality, the people engaged in wishful thinking are those who believe we can have a working Global economy without any legitimate systems of Global regulation.

Robert P Bruce – author http://www.TheGlobalRace.net

It seems increasingly unlikely that the OECD’s credibility as an international arbiter can survive the growing recognition – by everyone else – of the non-cooperation of Tax Haven USA, as well as the fact that Germany and UK benefit from their banking system hiding funds from other countries.

The Panama Papers have been heavily censored by ICIJ and most of the apologists of this form of cybertheft fail to acknowledge that in the few documents shared with the public:

– Most of the companies mentioned are not even from Panama, but from the UK Territory of BVI and several Commonwealth and US states,

– No Panama banks were involved, with the companies being requested by banks or intermediaries in UK, Switzerland, US and Hong Kong who signed commitments to comply with KYC regulations (obviously they lied),

– 95% of the Panama Papers cover documents from 1978 to 2013, before Panama signed agreements for tax information exchange with UK and several OECD countries,

– Those same countries have been unwilling to file formal information requests even after release of the Panama Papers, showing unwillingness of those OECD tax authorities to start effective prosecutions with the tools Panama has already agreed to provide. Those OECD tax authorities prefer to publicize black lists instead of prosecuting individual complicated cases.

All of the above serve as evidence that supervision of “global” tax transparency is a throw back to a XIX-century colonial and racist system when European superpowers imposed standards on Third World countries which they themselves are unwilling to follow. A truly global system should be based on consensus and mutual benefit.