Nick Shaxson ■ Did Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporate tax rate create the Celtic Tiger?

From the Fools’ Gold Blog, a new TJN-backed project on ‘competitiveness’. This article has also been cross-posted with Naked Capitalism.

Update, 2019: This issue is explored much more fully in the Celtic Tiger chapter in the Finance Curse book.

Ireland has long been a poster child for corporate tax-cutting. The standard argument goes something like this. “Ireland has very low corporate taxes . . . Celtic Tiger . . . just goes to show that corporate tax cuts grow your economy.” This argument is popular in Ireland too where government officials like to call the flagship 12.5 percent corporate income tax rate a “cornerstone” of industrial policy.

But is any of this even true?

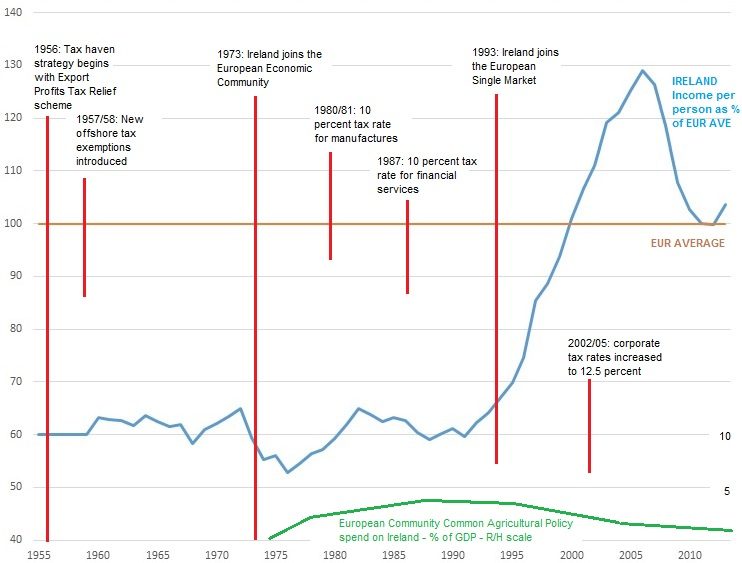

Well, now take a look at this little graph.

Chart 1: Ireland’s GNP per capita, relative to European GNP per capita, 1955-2013.

That’s a pretty clear picture of the so-called Celtic Tiger, now battered and bruised.

The graph casts serious doubt on the official story that multinationals and big accounting firms are desperate for people to believe (because this story is their meal ticket). The story is that Ireland’s low corporate income tax rate was a ‘cornerstone’ of Celtic Tiger-related economic growth.

Many people in Ireland and elsewhere have stopped even questioning the proposition that corporate tax cuts spur growth. But from first principles, it isn’t obvious why this should be so. A corporate tax is not a cost to an economy, but effectively a transfer within it*, shifting goodies to multinationals and their shareholders in the short term, at the long-term cost of fewer courts to enforce their contracts, or schools or roads or sewers. It is not obvious how this transfer necessarily spurs long term growth or makes an economy more or less ‘competitive’ (whatever that c-word may mean.)

So: what does the graph tell us?

Well, something happened in the early 1990s, when a huge surge began.

The inflection point came around the time of Ireland’s accession to the European Single Market in 1993. No geopolitical or domestic event or policy measure around that time came close to matching the importance of that. Note that the 12.5 percent tax rate was introduced long after the surge, and the 10 percent rate was phased in many years earlier.

The graph also shows how Ireland has been trying to be a corporate tax haven since 1956, but for decades it just did not seem to be working. Its relative economic performance basically flatlined until the mid 1990s.

Does our graph prove that Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporate tax rate doesn’t matter for Ireland? No: it could be that a tax haven policy only works in the context of an EU single market, of course.

So let’s try and see if this is the story. This next chart provides more context.

Chart 2: house prices, Ireland, Germany, United States

Now will you look at that yellowy-green Irish line, and how closely it resembles our graph at the top, timing-wise. That is a monster housing bubble, pricked by the financial crisis.

House prices are closely correlated with consumption. If your house doubles in value, you feel richer and you spend more. Consumption is a key component of GNP (and GDP). And joining the European Single Market clearly made a huge difference to what happened in Ireland’s housing market, as conditions changed, allowing Irish people to borrow freely and join the party. As Barry Eichengreen notes:

“Claims on the Irish banking system peaked at some 400 per cent of GDP . . . this was an exceptionally large, highly leveraged banking system atop a small island. It grew out of the high mobility of financial capital within the single market. It reflected [among other things] the freedom with which Irish banks were permitted to establish and acquire subsidiaries in other EU countries.”

Here we have the single market again, and the Eurozone, behind the surge.

But that is not all. Look at our top chart again, and consider what might have caused that possible mini-surge in the mid to late 1970s. Was it a dead cat bounce? Reversion to the mean?

Well, the timing again may point to Europe: specifically, to Ireland’s accession to the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973. And was this it? Well, here’s Prof. Frank Barry from University College, Dublin, in a paper about Ireland’s economic development:

“Within manufacturing, EU entry brought a further substantial increase in employment in foreign-owned industry, with the number of jobs in this sector expanding by almost 40 percent between 1973 and 1980. This was to be expected as a consequence of the integration of a relatively low wage economy into the large EU market.”

We also need to factor in all those lovely subsidies to Irish agriculture, which you can see in the lower green line in our top chart, and in more detail here below.

Europe again, at the heart of the story. And those are some hefty subsidies by Irish standards, rising to an average net 1.3 billion Euros-equivalent annually by the early 1990s on the evidence of this graph. (Equivalent-sized net transfers for the UK and US would come to over 15 billion and 120 billion Euros annually, respectively). And in this data we haven’t even included all those other European Development Funds (click on that link to look at the scale and diversity of the European funds Ireland has been tapping.)

In short, truly whopping transfers for Ireland. Yet the PR machine of the Irish tax haven and for corporate tax-cutters rarely cite these factors. Why would that be?

Have low corporate taxes attracted investment?

These graphs don’t tell us, however, whether or not the low-tax policies (which, by the way, include not just the 12.5 percent rate, but lax transfer pricing rules and patent boxes and other wheezes which can cut effective tax rates close to zero) have been successful in attracting multinational investment.

They certainly must have done – but just how relevant is this anyway? What we want to know is not whether these policies have been good for one sector, but whether they have been good for Ireland as a whole. If Ireland has had to shower investors with tax subsidies to get them to come, meanwhile losing tax from those who would have invested anyway, the cost may well not have been worth it.

On this less important metric we haven’t seen any clear demonstration as to whether Irish corporate tax policies have helped Ireland or not.

We’d argue that Ireland’s key selling point for U.S. firms has been its combination of English language, close cultural historical and economic connections with the United States, its educated workforce (including many immigrants, educated on someone else’s dollar) and its membership of the Eurozone and the EU single market. The graph shows clearly how important the latter factor is, though it doesn’t discount the tax offering. (We should also mention Ireland’s Wild west financial regulation — what they liked to call the “flexible and business focused tax and regulatory system” which brought in a lot of shark-related business, eventually contributing to the Global Financial Crisis and the Celtic Tiger’s spectacular flameout.)

Most of these aren’t easy to replicate: after all, how many other English-speaking Eurozone members with deep cultural connections to the U.S. can there be? Tax is certainly one factor that attracted some investors, but the weight and range of these rare (and mostly good) Irish attributes suggests that Ireland would have got a good chunk of this investment anyway. In which case, it has probably thrown away a lot of tax revenues to the shareholders of a bunch of U.S. multinationals, unnecessarily.

Let’s not forget, too, that there is investment and there is investment. Stuff that gets lured to low tax countries generally tends to involve a lot of accounting nonsense, rather than real economic activity. If it’s tax-sensitive then it is, by definition, flighty, and not so embedded in the local economy. But it’s the embedded stuff (that isn’t tax-sensitive) that countries generally need to attract: the stuff that brings real jobs and skills transfers and so on.

The trouble is, those making huge profits from the accounting nonsense are designing Ireland’s tax policies and are key players in the spin machine that protects the Ireland tax haven. And most of Ireland’s media and political class seems to have drunk the Kool-Aid — as have many others, elsewhere, who point to Ireland as the poster child.

How sustainable is all this? The graph doesn’t provide answers, but it’s surely true to state (as Jim Stewart does in this 2015 discussion paper) that:

“a tax based industrial policy will not result in an innovative, research led economy.”

Indeed.

Endnote: the UK

The UK has tried to emulate Ireland recently in many of these things. Like Ireland, it has the English language and interconnectedness, in spades, though it isn’t a member of the Eurozone. This means two things for our analysis here. First, it shows that Ireland is trapped in a race to the bottom with the UK (and over time, perhaps with Northern Ireland and Scotland joining in this fools’ errand). Second, the evidence so far suggests that the UK’s corporate tax-cutting policies have failed comprehensively to bring anything more than a few jobs for bean-counters, at huge cost.

In the UK, it seems pretty clear that the corporate tax nonsense has been great for multinationals and their shareholders – but not so great for the country as a whole (more on this in due course.) Is it the same story for Ireland?

Read more

Take a look, again, at Barry’s paper, which looks at quite a bit of the history of this tax haven activity, and at the Tax Justice Network’s rollicking history of how Ireland became a wild-west tax and financial regulatory haven, and all the associated links. See also Jim Stewart’s paper Corporate Tax: how important is the 12.5% corporate tax rate in Ireland?

Data sources.

There is a certain amount of data on Irish GNP here. The latest data doesn’t go back far enough, so we had to use reports going back a few years, such as here. This doesn’t yet get you to the GNP/capita as a share of EU GNP capita, so for that we used the data set here (p24), and this one, (p27), to get the final graph. We could have simply used this last data to create an even more dramatic picture but for countries like Ireland where ‘local’ corporate profits are often little more than accounting nonsense with few connections to the local economy, then GNP is a better measure than GDP, if you want to know things like whether this stuff is making Irish people’s lives any better or not. We assumed that European average GDP was the same as average European GNP over this time, which is pretty reasonable because this is usually the case with countries: Ireland (and Luxembourg) are extreme outliners: see Figure 1 here, for instance.

For the net agriculture payments (dark green line in top chart, and third chart), it’s here.

The main blue line in our graph is a good-enough approximation to show what’s going on. You can quibble with it, of course. For one thing, the data set of countries changed slightly over time, from the EU-12 to the EU-15. Doing all the legwork there won’t make much difference. We also only had data going back to 1960, but we wanted to go back to 1955, the year before Ireland’s tax haven strategy began. We didn’t have the pre-1960 data, so we created a short flat line there. (If you have the earlier data, please let us know.) You can also quibble with the timings we’ve expressed here: some of these tax changes were somewhat more complex than we’ve been able to fit into our little captions in the graph. For instance, the introduction of the 12.5 percent tax rate also involved expanding the range of what qualifies for that rate.

* Modern Monetary Theorists and others may quibble with this line, arguing that tax revenues aren’t entirely necessary for spending, but the fact is that governments for whatever reason generally feel they need to match spending with revenues, more or less, over the long run, so there is a loose relationship.

Related articles

UN tax convention hub – updates & resources

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The bitter taste of tax dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

Taxing windfall profits in the energy sector

14 January 2026

Most American IT companies in Ireland make a deal with Ireland that give them a corporate tax of 0%

It seems agreed that it’s the shareholders that we are trying to tax through corporate income taxes. Why don’t we rely on taxing them directly on their dividends and capital gains, and do away with corporate income taxes altogether? Companies don’t consume, only their employees, owners and customers do. The less tax that companies pay, the more their investors will do, once they actually draw their income.

Maybe 0% corporate tax doesn’t actually matter, and the sooner we get to that rate everywhere, the sooner we level the playing field.

“It seems agreed” is quite wrong. See the document “10 reasons to defend the corporate income tax” for more.

http://www.taxjustice.net/2015/03/18/new-report-ten-reasons-to-defend-the-corporate-income-tax/

This TJN ten reasons doesn’t really address the point I was making, which is that the money inside corporations does get taxed eventually, when it is distributed to shareholders (or managers and staff), so why worry about taxing it inside the corporations?

I do see that it may be technically more efficient to collect from one big company rather a multitude of stockholders, and less easy to evade.

I also see that leaving more money rather than less in the hands of corporate bosses proportionally increases their partisan power and influence, for instance over the political process.

If you do not agree that Corporate Taxes are designed to be incident on shareholders, then who do you think they actually fall on?

If you read the document, you’ll see that we take the position that corporate taxes fall principally on shareholders. And if you don’t tax corporations, you open up a world of shenanigans, and you fatally undermine the personal income tax, and transmit damage around the world. If you don’t tax the corps, you’ll find that most of those corporate shareholders escape or are exempt from tax on their corporate income. The rich ones with good accountants, anyway.