John Christensen ■ Corruption behind closed doors

Here’s an interesting new map of corruption and illicit financial flows. In this blog titled Is it time for a Different Look at Mapping Corruption, James Cohen, picks up on work by TJN, Global Witness, and Washington-based Global Financial Integrity, and suggests that the time is ripe for leading anti-corruption NGO Transparency International to expand its mapping of corruption (based upon its Corruption Perceptions Index) to bring the secrecy jurisdictions which provide anonymous legal vehicles into their focus. As Cohen notes:

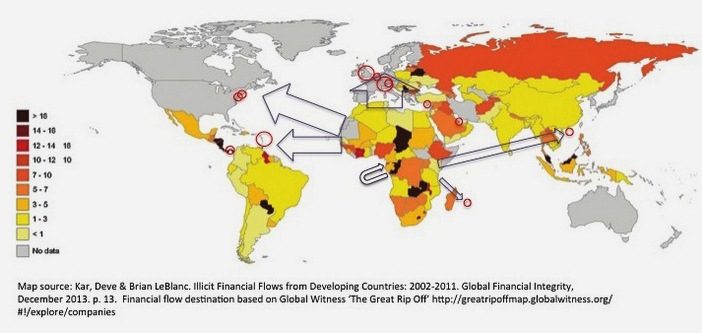

Most stolen money leaves the country where the theft occurred. Those funds often move to developed countries, which the CPI displays as low in corruption. For the most part, citizens in those yellow countries don’t experience corruption on a day-to-day basis; rather, corruption there mostly happens behind closed doors and as we have recently seen with respect to many of the recent enforcement actions, those are often Western bank doors.

As his map shows, the vast majority of illicit financial flows out of Sub-Saharan Africa head northwards towards Europe and North America, with British Virgin Islands, Hong Kong and Mauritius becoming increasingly important players.

TJN has argued for a long time that the corruption debate needs to take account of the role of facilitating agencies that handle the proceeds of corrupt practices. In his 2007 paper, Mirror Mirror on the Wall, Who is Most Corrupt of All, TJN Director John Christensen argued that western law firms, western banks, and secrecy jurisdictions politically linked to major OECD countries like Britain and the USA, have played a major part in creating a globalised criminogenic environment. As Cohen points out in his blog, a new map of cross-border illicit financial flows, will go a long way to shifting discriminatory perceptions that corruption is something that largely happens in the global South, while the countries of the global North are squeaky clean:

A new map showing illicit financial flows would still face the corruption data challenge of complete accuracy, but it would go a long way in helping bring the discourse on illicit financial flows to the public and it would break the mentality that ‘we’ (in the West) are clean and ‘they’ (in the rest) are corrupt. Instead, it would show the shared challenge of combating corruption and allow deeper analysis into the factors facilitating specific illicit financial flows.

Read James Cohen’s blog here.

Related articles

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025