Nick Shaxson ■ Apple’s tax affairs: a symptom of the robber-baron culture

Updated with further information about Brazil’s decision – see below.

Now also on Angry Bear, Middle Class Political Economist

From the Financial Times:

More precisely, a group of 185 American CEOs has sent letters, co-ordinated by the Business Roundtable lobby group, to the leaders of 28 EU member states to try and get the European Commission to row back from claiming €13bn in underpaid taxes from Apple. They call the attempt a “grievous self-inflicted wound”.

Let’s be clear. This isn’t a sudden, political tax grab by the EU. This is an investigation into violations of “state aid.” That is, market-distorting behaviour. Monopolies and all that. Tax just happens to be the particular form of state aid in this case. (Read Ed Kleinbard’s excellent opinion piece, also in the Financial Times, on this.)

What is perhaps more interesting is the clear signal that this group of US multinationals sees a common interest in defending Apple – because, presumably, they recognise that what they’re really defending is the principle of international tax rules that don’t work. To be fair, they’ve had a great run. Our research shows US multinationals went from shifting just 5% of their global profits away from where their activity took place in the early 1990s, to 25-30% in the most recent period. But both the public and policymakers have had enough. While the lobbyists ensure that recent OECD reforms were largely toothless, the appetite for real change has not diminished. Quite the opposite, in fact.

For years we’ve argued that multinational tax dodging favours monopolists and market-riggers, at the expense of consumers and workers: a second round of damage, if you like, after the tax losses. This new report in The Economist is just the latest to raise the alarm about the perils of fast-rising market dominance.

In this spirit we’d like to draw an attention to another article today in the Financial Times, by their columnist Philip Stephens. It’s called How to Save Capitalism from Capitalists, and it reminds us that this fight is much bigger than tax.

“It would be something of an understatement to say that these businesses are angry about the probes. The banker John Pierpont Morgan thought he could treat Roosevelt as an equal. With something of the same righteous indignation, Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, lambasts the European Commission’s ruling as “political crap”. Never mind that Apple funnels revenue though “stateless” entities unaccountable to any tax authority. Mr Cook seems to believe his business operates on a higher plane than that occupied by mere politicians or regulators.

. . .

The public perception is that the companies reaping the rewards of globalisation are beyond reach of the rules that apply to everyone else. All the insecurities of globalisation fall on ordinary citizens.

. . .

There will always be business leaders true to the tradition of the old robber barons who think theirs is a superior calling and that democratic politics is, well, “crap”.“

The arrogance of these companies — especially technology companies which pose threats to all our societies and democracies in a range of other ways — beggars belief. Stephens sets the right tone here:

“It is too soon to pass Roosevelt’s mantle to Ms Vestager. But everyone who supports the liberal market economy that made possible the success of Apple, Google and the like should be applauding her courageous effort to reset the balance.”

Those campaigning for tax justice need to keep building alliances with those concerned with curbing the rising power of monopolies. And the EU, in response to this pushback, now needs to go seriously on the offensive with its antitrust efforts. And not just the EU. As an aside, some breaking news:

This is about Irish shenanigans again. Apple has already paid up, apparently. And in this story, there’s this:

“Separately, a report by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry criticised Apple and Google for actions it said could potentially undermine competition in the market for smartphone apps.”

Interesting times.

One last thing. EU commission thing isn’t best seen as a fight between the EU and the US. This is a fight between robber barons and ordinary folk in both the EU and the US – and beyond.

There is the side of justice and democracy, and there is the side of the robber barons. Which side are you on?

Update, Sept 19th. See this informative press release from the Irish political party Sinn Féin, entitled Tax inversions behind Brazil’s move to place Ireland on tax haven list – Carthy. Among other things, it takes to task a widely ridiculed 26 percent GDP growth figure for Ireland, a widely cited number which is based on jobless profit-shuffling (in large part due to corporate inversions). See more about that here.

An older update from Ireland: a last word to the Irish Times’ always excellent commentator Fintan O’Toole:

“It’s been interesting, over the last fortnight, to smell the fear in the air. The fear of making big decisions. The fear of the unfamiliar. The fear that if we try to impose basic standards of decency on multinational corporations they will simply leave us to our own pitiful devices.

. . .

The fear of the last fortnight is that if you take away our status as a tax haven for huge global corporations we won’t have much left. We’re so insecure that we worry that unless we allow these corporations to use our green and pleasant land as a conduit for untaxed billions, they’ll leave us for a more compliant lover.

. . .

This place is not so bereft of attractions that it can entice investment only by advertising itself as a moral no-man’s-land. We’re better than that – not the best little country in the world, not God’s chosen people, but not a glorified financial brothel either.”

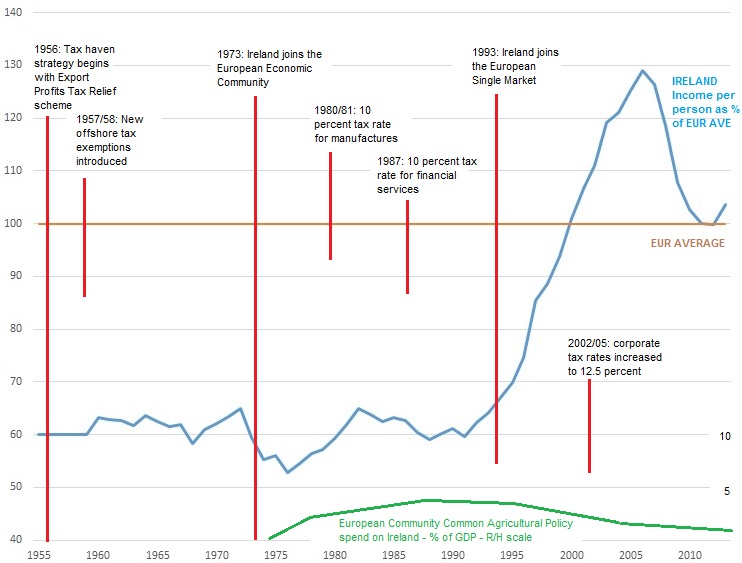

Quite so. And this graph, which we’ve used several times before, underline his point. Ireland’s big attractions lie elsewhere. Make the most of them.

And this is bolstered by what was happening on the ground. Consider the chronology here:

“Apple first arrived in Ireland in 1980 when it launched a manufacturing plant in Holyhill, above Cork. Steve Jobs announced £7 million in investment in the country, along with 700 new jobs.

10 years later, after employing hundreds of people, Apple met with the Irish government to talk tax.”

Just saying.

Related articles

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

The People vs Microsoft: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Can the UN succeed? Top questions about our State of Tax Justice report

Switzerland’s tax referendum is a choice between tax havenry and more tax havenry

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #66: الضريبة الموحدة على الشركات والفرص الضائعة

Monopolies and market power: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #62: بولط تونس: تسريب معطيات نحو تل أبيب، تهرّب ضريبي وجرائم أخرى

The Making of Tax Haven Mauritius: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Dear TJN,

Your graph says, 2002/2005 corporate tax rates increased to 12.5 percent. Often people say it was decreased to 12,5%. I’m debating this right now. Please see this graph, which shows tax sharply falling from 1988:

http://www.maroc.nl/forums/het-nieuws-van-de-dag/389905-amerikaanse-reuzen-vragen-om-belastingverlaging-post5551513.html#post5551513

Can you please elucidate this?

Best wishes, Olive Yao

Great post! Only one observation about Ireland (and Luxembourg). What is fundamental for Ireland’s success is not “almost zero taxation” per se. But this zero taxation in combination with the European Single Market. The possibility of accessing the single market, i.e. the biggest market in the World, is what makes the difference with respect to being a caribbean paradise. The combination of the two transformed the European Union in the biggest fiscal paradise for corporations that human history recalls.

Well, in theory you could be right. But the traditional story is that corporate taxes were “decisive”. This graph tells a very different story. Low effective corporate taxes may have increased investment, at the margin, but if they’d had higher effective taxes they would most likely have received all or almost all that investment, with a much higher tax take. A much more sustainable situation: healthier from pretty much any angle you can think of, whether Irish or international.

Dear marc and Nick,

The graph originally comes from another TJN article,

Did Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporate tax rate create the Celtic Tiger?

https://www.taxjustice.net/2015/03/12/did-irelands-12-5-percent-corporate-tax-rate-create-the-celtic-tiger/

It’s worth reading.