Nick Shaxson ■ The Bahamas tax haven – a (re-)emerging global menace?

Update: as it happens, The Economist has just published an excellent story about the Bahamas, subtitled The Bahamas Cocks a Snook at the War on Tax Dodgers. (Our only beef with that subtitle is that this is about so much more than just tax.)

Update: as it happens, The Economist has just published an excellent story about the Bahamas, subtitled The Bahamas Cocks a Snook at the War on Tax Dodgers. (Our only beef with that subtitle is that this is about so much more than just tax.)

We’ve periodically remarked on the Bahamas as a secrecy jurisdiction of great concern. Like Panama, it’s generally had a greater tolerance of dirty money than most modern offshore centres: more of a willingness to turn a blind eye and to overlook noncompliance by Bahamas-based actors of its own rules and laws.

The purpose of this blog is to flag up the Bahamas in a more pointed way: as a major wrecking-ball threatening global efforts to clamp down on cross-border financial secrecy.

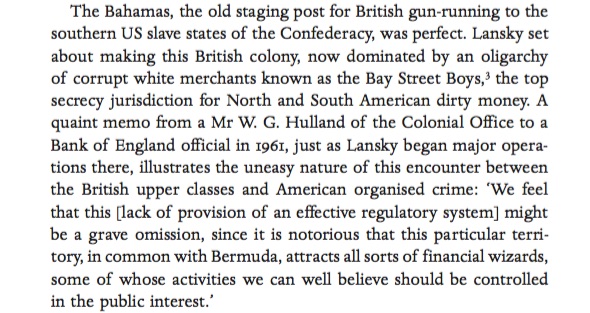

The Bahamas has hosted an offshore centre for crime and tax evasion for decades, and it has historically had a higher tolerance for dirty money than most tax havens. Its secrecy score of 79 in our Financial Secrecy Index is one of the world’s highest. Treasure Islands summarises an important component of the Bahamas’ history and identity, via Chicago gangster Al Capone’s moneyman, Meyer Lansky:

More recently, we have become aware of two closely related matters of concern.

The first concerns the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard project, a global scheme for countries to share banking information across borders. The Bahamas is, in essence, thumbing its nose at this project – saying, in effect, that ‘we are the dirty-money centre of choice’ – and it is currently attracting a lot of financial activity as a result. Second, the Bahamas government is sending out delegations around the world, to all and sundry, advertising itself as a holdout against proper compliance. And it’s doing this via typically tax-havenish devious methods. As one notorious offshore promoter puts it:

“The government of The Bahamas . . . is highly proactive in its attempts to attract offshore business, which accounts for over 30% of the country’s economy.”

The second, related problem is that the OECD doesn’t (yet) seem to be doing anything about this. We do expect that the OECD will be pushed and prodded towards action soon, and we expect the criticism of The Bahamas to rise very significantly in the near future, and the Bahamas will eventually be forced to change tack.

What Bahamas is actually doing

It’s fairly straightforward. Now the Bahamas has committed to the CRS system, but in a particularly narrow way. From the Bahamas Weekly:

“The optional methods of implementation defined by the OECD are a multilateral and bilateral approach, both of which adhere to the international standards for tax cooperation and tax transparency.”

All of which is true. The key question is: does your country engage with the CRS multilaterally, or bilaterally? Do you exchange with the world, or do you cherry-pick which jurisdictions you’re going to exchange with? In general terms, cherry-picking means exchanging information with a) powerful jurisdictions they’re afraid of antagonising, like the United States, and b) jurisdictions that don’t matter to their offshore industries, like the Faroe Islands. And the rest – the ones that matter, frequently developing countries that are most vulnerable to looting by their élites – get full-service secrecy for those same crooked élites. ‘We’ll take your dirty money, and we’ll cover it up.’

Now the OECD has been fairly successful in corralling countries into the multilateral approach.

As of August 19th, a total of 84 countries, including nearly every major tax haven, had signed up to the multilateral approach. Among the important tax havens there are three noticeable hold-outs which haven’t signed: Singapore, Panama and . . . the Bahamas.

All deserve extreme opprobrium. But of these three, the Bahamas’ approach is by far the worst. This is because Panama (under tremendous, scandal-fueled global pressure) and Singapore have both signed (and Singapore has ratified) the so-called “Multilateral Convention on Mutual Legal Assistance in Tax Matters, an older instrument which is the legal basis for exchanging information under the CRS. Bahamas hasn’t even signed that. Armed with this legal basis, Singapore could sign an information-sharing agreement with Indonesia tomorrow, and Panama could sign with Brazil. But if Bahamas wanted to exchange with someone, they’d have to go about the long, arduous process of indiviually negotiating a “Tax Information Exchange Agreement” with that jurisdiction.

A tax adviser put it to TJN like this:

“Singapore and Hong Kong: they have a law which says ‘if you suspect the money is untaxed you should file a suspicious report.’ Bahamas is like ‘what’s suspicious about this suitcase full of money?’

The Bahamas Ministry of Finance is crowing about this. In a briefing on the subject, not only spells out but emphasises that it has failed to sign the multilateral instrument necessary to participate, with a single isolated sentence:

“The Bahamas is NOT a signatory to this Convention.”

Their emphasis added. Make no mistake: this is a giant, fist-pumping Screw-You to the civilised world. The Bahamas is loudly advertising its desire to take criminal money. And, as mentioned, they’re aggressively sending delegations out to places like Mexico and Colombia, which are suffering terrible violence and murder because of their drugs wars, and advertising an open shop to the drugs cartels. As the Best of Both Worlds site puts it, on a page dedicated to the CRS:

“The Bahamas government delegations travel globally, sponsoring seminars, attracting new business by assuring financial industry intermediaries that Bahamas will categorically not undertake exchange of information with many countries, especially Latin America, due to bogus security concerns.”

Bahamas’ excuse for going this way is twofold. First, it cites bogus data security concerns. (If you think such concerns are legitimate, read this.) Second, it says that the multilateral approach isn’t appropriate for jurisdictions ‘with a direct taxation regime.’ Pure nonsense. Look at all those tax havens without direct taxes that have signed the multilateral instrument.

Other recalcitrants

So that’s the Bahamas. We can’t finish this blog without reminding our readers of other key recalcitrants, however. We’ve already pointed out thatthe OECD has inexplicably allowed cherry-picking even inside the multilateral instrument. (Switzerland does this, not just to its shame, but also to the shame of the OECD, which tolerates this.)

And then there is the United States, which has opted out of the CRS entirely, instead forging ahead with its own system, which it says is equivalent to the CRS, but most certainly isn’t.

Related articles

Just Transition and Human Rights: Response to the call for input by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

13 January 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

The Tax Justice Network’s most read pieces of 2024

Did we really end offshore tax evasion?

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Stolen Futures: Our new report on tax justice and the Right to Education

Stolen futures: the impacts of tax injustice on the Right to Education

31 October 2024

How ‘greenlaundering’ conceals the full scale of fossil fuel financing

11 September 2024

As you say, it’s more than about tax. The fact that the boats that ply between the UK and tax haven Jersey are registered in Nassau speaks volumes.