Nick Shaxson ■ Some countries “lose” 2/3 of exports to misinvoicing

From UNCTAD, the UN Conference on Trade and Development, via email:

From UNCTAD, the UN Conference on Trade and Development, via email:

“Some commodity dependent developing countries are losing as much as 67% of their exports worth billions of dollars to trade misinvoicing, according to a fresh study by UNCTAD, which for the first time analyses this issue for specific commodities and countries.

Trade misinvoicing is thought to be one of the largest drivers of illicit financial flows from developing countries, so that the countries lose precious foreign exchange earnings, tax, and income that might otherwise be spent on development.”

Trade misinvoicing is a form of money laundering that involves deliberately misreporting (on an invoice) to customs the value of a commercial transaction, in order to shift money illictly across borders. So, for example, a Tanzanian exporter selling goods worth $100 might submit an invoice to the Tanzanian customs authorities saying the goods were sold for only $80. They receive $80 through normal channels, satisfying the customs authorities. But in reality, the foreign seller paid $100: the additional $20 is paid into a secret bank account somewhere. Tax havens are widely used for this practice: not just because of their secrecy, but also because their more general tendencies of turning a blind eye to this kind of fraudulent and criminal activity.

Léonce Ndikumana, lead author of the report, said that the discrepancies in the trade data, which are the basis for estimating reinvoicing, were systematic and growing over time: this is not the result of errors in recording this stuff.

“The implication is that it is the operators who are explicitly manipulating the invoices. There has to be complicity on both sides. There’s a serious lack of transparency on both sides.”

Switzerland, for instance, is and remains a giant turntable for this kind of thing: despite having made some (ultimately limited) concessions on secrecy to powerful countries like the United States, it remains robustly secretive towards weaker more vulnerable countries. And of course the actual physical commodity doesn’t generally run through the Swiss turntable: only the paper trail.

The Berne Declaration in Switzerland published a crucial and highly regarded document in this area entitled Commodities: Switzerland’s Most Dangerous Business. It explained:

“On the whole, the commodities business as practised in Switzerland today is dangerous for all countries in the southern hemisphere that are blessed with natural resources but at the same time suffer from weak or corrupt governments.”

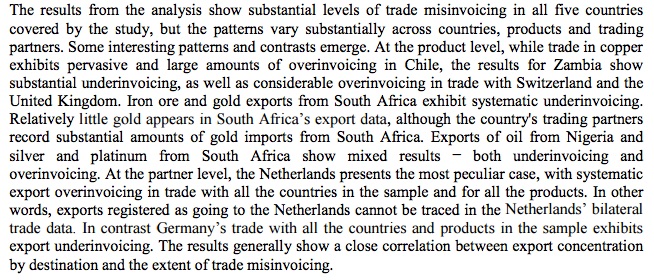

Back to the UNCTAD report, which focused on five commodity-dependent countries – Chile, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia:

“In the case of Zambia, 51 per cent of its leading export commodity, copper, is exported to Switzerland.”

The study notes that, beyond Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Netherlands and Germany also play a major role in the problem:

The Financial Times covers this story, in an article entitled Misinvoicing of commodities costs billions to developing world:

“The scale of the problem exposed by the new report should prompt governments in commodity exporting nations to prioritise tackling misinvoicing over chasing new investment, donor funding or issuing debt, one senior UN official said.”

It adds:

“Alex Cobham of Tax Justice Network, a UK advocacy group, called for governments to demand greater transparency, especially from trading hubs such as Switzerland, which he described as “a data black hole”.

“We can see that commodities leave developing countries, often at abnormally low prices, destined for traders there; and then the trail goes cold,” he said. “The clear risk is that the secrecy of Swiss and other trade provides the cover for even greater misinvoicing than we see in the available data.”

Cobham adds:

“It strongly supports the view that misinvoicing is a problem of first-order economic importance for developing country commodity exporters. It also shows that the risks are likely to be greatest where the partner countries are not the final destination, but trading hubs such as Switzerland and the Netherlands – especially when the physical product does not actually pass through the hubs.

Overall, the study confirms that the current level of commodity trade transparency is simply insufficient. Using 4-digit commodity data is a clear step forward from estimates based on national-level data, which cannot be relied upon; and indeed there is scope to use more detailed commodity code data to take this analysis further in future. But the remaining issue is the lack of transparency from trading hubs such as Switzerland, which become a data black hole.

There are three important steps that follow. First, Switzerland and other hubs must be prevailed upon to publish the data they collect on merchanting and transit trade, disaggregating by type and for freeports, so that there is equivalent transparency. Until they do so, partner countries may wish to consider whether Switzerland and other hubs are meeting their WTO obligations not to undermine the benefits of trade for other countries, by imposing this opacity.

Second, developing country commodity exporters may wish to step up their work at customs, and in particular to require final destinations for exports – so that a Swiss-based trader cannot be given as the recipient for copper destined for China, for example.

Third, this study underlines the value of having fully disaggregated trade data. Customs authorities should consider sharing, and publishing – or at least making available to researchers in a consistent manner – their anonymised transaction-level data. Ultimately, it is only through identifying consistent abnormal pricing by particular traders that it will be possible to curtail sharply the illicit flows that Ndikumana et al show to be rife still.

Update: there are dissenting voices out there on this analysis: we will discuss these shortly.

Related articles

Just Transition and Human Rights: Response to the call for input by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

13 January 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

The Tax Justice Network’s most read pieces of 2024

Did we really end offshore tax evasion?

Stolen Futures: Our new report on tax justice and the Right to Education

Stolen futures: the impacts of tax injustice on the Right to Education

31 October 2024

How ‘greenlaundering’ conceals the full scale of fossil fuel financing

11 September 2024

10 Ans Après, Le Souhait Du Rapport Mbeki Pour Des Négociations Fiscales A L’ONU Est Exaucé !

CERD submission: Racialised impacts of UK’s ‘second empire’