Alison Schultz, Franziska Mager ■ How “greenlaundering” conceals the full scale of fossil fuel financing

This report was produced in collaboration with Banking on Climate Chaos, whose support was essential to our analyses. We also greatly appreciate the valuable resources compiled by urgewald e.V. and Reclaim Finance.

Disclaimer: The Tax Justice Network considers the information communicated in this report to come from reliable sources and has taken every care to ensure its accuracy and that the data analysis is robust. Full details regarding data sources and methodological decisions can be found in the accompanying methodology note. However, given the opaque nature of the subject matter, the Tax Justice Network cannot warrant the absolute accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information or analysis and disclaims any liability for the use of this information or analysis by third parties. If you believe there are inaccuracies in our data, please reach out to us at [email protected], and we will make every effort to investigate and correct any errors as necessary.

This analysis identifies structural deficiencies based on aggregated data. The individual examples given are used to illustrate the risks, and we do not assert that any of the companies named are actively violating laws or regulations.

Executive Summary

The global financial system is still fundamentally at odds with climate goals, as it continues to entrench high-carbon development pathways. In this report, we demonstrate that financial secrecy plays a key role in perpetuating this issue: it enables banks and fossil fuel companies to obscure the true scale of their fossil fuel financing – a practice we term “greenlaundering.” Unless steps are taken to dispel this smog of financial secrecy, progress won by the climate justice movement to divest from fossil fuels will continue to be jeopardised.

This report examines the fossil fuel financing provided by the 60 largest global banks, exploring how funds are strategically channelled through “secrecy jurisdictions.” These type of tax havens, specialized in financial secrecy, allow firms to obscure their activities and ownership structures from the public. Fossil fuel company subsidiaries appear to be deliberately established in secrecy jurisdictions to take advantage of weak transparency regulations and favourable tax regimes.[1] The report also offers indicative evidence of how these structures benefit both fossil fuel companies and their financiers – at the expense of the climate and a liveable future for us all.

Our analysis of fossil fuel financing of the world’s largest 60 banks reveals:

- 68 per cent of the fossil fuel financing provided by the world’s 60 largest banks is being granted to subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions. With their weak transparency laws, such jurisdictions allow fossil firms to hide details about their ownership structures and financial activity or enable them to pay lower taxes than they should.

- It is widespread practice among fossil fuel companies to establish financing subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions, from which they move funds to expand fossil fuel activities in other locations. These companies often have complex subsidiary structures spread across various secrecy jurisdictions, making it difficult or even impossible to trace the flow of finances.

- Since the majority of fossil fuel financing flows through secrecy jurisdictions via complex subsidiary structures, it becomes difficult to quantify banks’ true fossil fuel exposure. This challenge is further compounded by the lack of transparency regarding the final use of each type of financing. As a result, ensuring the accuracy of banks’ sustainability reporting, as well as their adherence to exclusion policies and regulatory measures – particularly those focused on transparency in sustainable finance – becomes increasingly difficult. What we observe resembles a “hall of mirrors,” where deals are concealed by layers of complexity and obfuscation.

We illustrate the problems of such structures based on two prominent examples of fossil fuel companies: Aramco, the world’s largest oil company, and Glencore, the world’s largest coal producer and exporter. These companies’ responses, and those of others named including a range of banks, are included in full in the accompanying methodology note.

Our detailed investigation of Aramco’s and Glencore’s financing structures reveals:

- The “hall of mirrors” makes it nearly impossible for activists, researchers, financial regulators, and the public to identify all subsidiaries that are relevant to the companies’ financing structures.

- Even when a subsidiary can be linked to a fossil fuel company, its location in a secrecy jurisdiction makes it difficult or even impossible to obtain information about the firm’s owners or financial situation. This is a concerning pattern for anyone trying to assess the financial health of a fossil fuel multinational.

- Even for subsidiaries where basic information can be obtained, it remains impossible to determine how the financing received is eventually transferred and used.

This lack of transparency makes it difficult to hold fossil fuel companies and banks accountable for their continued investments in polluting sectors. It also complicates regulators’ efforts to enforce rules related to both sustainable finance and financial stability. Meanwhile, the largest fossil fuel firms and global banks may benefit from this opacity at the expense of broader accountability.

Our analysis of potential secrecy benefits for the largest fossil firms shows:

- Exploiting financial secrecy can enable fossil fuel companies to secure more favourable financing conditions. Specifically, we find that financing channelled through subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions is associated with lower interest payments for fossil fuel companies. This may be because such financing is not classified as “fossil fuel financing” by banks, allowing it to be offered under more advantageous terms and could be a method by which fossil fuel firms circumvent existing bank exclusion policies.

- A strategic arrangement of various financing schemes can further reduce the cost of funding for fossil fuel companies. Under the current system, these firms can obtain favourable lending conditions for the “greener” parts of their business, such as renewable energy projects, by using “Green Bonds” that offer lower financing costs. Simultaneously, the same company could secure funding for its fossil fuel activities without penalties by structuring it through subsidiaries that are not classified as “fossil fuel financing” and labelling it as “general purpose funding.”

- A well-known benefit of using low-tax jurisdictions – common not only in the fossil fuel sector but across industries – is aggressive tax planning. Channelling finances through secrecy jurisdictions allows fossil fuel companies to shift profits to locations with the lowest tax rates. For example, a loan received in a low-tax jurisdiction can be passed on to other group entities at higher interest rates, effectively moving money from higher-tax countries, where the interest cost can be deducted against profits subject to higher tax rates. This enables companies to reduce their tax burden and avoid paying the fair share of taxes owed, given the economic activity they have in each country.

The largest banks may be complicit in these arrangements, as it allows them to remain unaware – or deliberately avoid knowledge – of fossil fuel activities they would rather not recognize, a practice we refer to as “planned ignorance.”

Our analysis of potential benefits for global banks from secrecy deals shows:

- Banks appear to understate their true exposure to the largest oil, gas, and coal companies compared to our findings. This allows them to greenwash their image and technically comply with self-imposed sustainability metrics, while still maintaining lucrative relationships with profitable clients they would otherwise be expected to cut ties with.

- This understatement can be attributed to several factors linked to secrecy practices: banks may not report the fossil fuel exposures of the corporate group if they have granted financing to one (potentially non-fossil fuel related) subsidiary of this group only, they may exclude certain types of financing, and they might apply generous definitions and high thresholds when designating companies as fossil fuel firms.

- An analysis of the exclusion policies of six of the largest global banks reveals that only one explicitly considers the activities of all subsidiaries within a corporate group in (at least parts of) its fossil fuel exclusion policies. This loophole allows banks to continue financing an excluded company through one of its subsidiaries or through subsidiaries under the same parent company.

- Banks likely understand that funding can be shifted between subsidiaries. Therefore, they should take subsidiary structures of fossil fuel companies into account – especially those of large, diversified energy groups – when defining exclusion policies and reporting fossil fuel exposure.

- “Planned ignorance” can prove useful when a bank only reports what it officially knows, for instance, in the context of the EU’s sustainable finance and corporate sustainability reporting requirements. This approach may also explain why banks avoid formulating clear and ambitious exclusion policies – such as including all forms of financing to any fossil fuel subsidiary, no matter their own exact role in the financing – and why the available data on banks’ fossil fuel financing does not align with their sustainability reports.

Greenlaundering harms us all. The opaque nature of fossil fuel financing through secrecy jurisdictions prevents policymakers and regulators from fully enforcing regulations. Investors seeking to invest sustainably are unable to access transparent data. It also weakens the ground for climate advocacy: the goalposts for the climate justice movement in bringing about the permanent divestment from fossil fuels are constrained by the very limited information that is publicly available.

Tax justice is key to fighting greenlaundering and dispelling the hall of mirrors that enables it. Jointly with increased reporting transparency and continued pressure on both banks and fossil fuel corporates, we can hold them to account.

Specifically, we propose the following recommendations:

- Negotiate transparency rules at the UN: Financial secrecy is a global issue that requires multilateral cooperation, best achieved through transparent and inclusive processes. The recent agreement to establish a UN Tax Convention marks progress towards a global transparency framework. This shift can take the world beyond the historically opaque and discriminatory OECD negotiations, and offers a chance to connect tax and climate goals at the highest level of governance.

- Unmask polluters through comprehensive beneficial ownership transparency: Identifying the individuals behind fossil fuel companies and their subsidiaries would expose financial secrecy and reduce their ability to hide polluting activities. Publicly accessible beneficial ownership transparency would make it harder for companies to shift funds through subsidiaries unnoticed, helping dismantle “planned ignorance” by banks.

- Improve public country by country reporting for corporations: Requiring multinational corporations, including fossil fuel companies, to disclose their economic activities, profits, and taxes paid in each country would reveal potential abusive practices. Stronger reporting standards would uncover the use of secrecy jurisdictions to conceal fossil financing and thereby combat “greenlaundering”.

- Pressure banks to phase out investments in dirty fossil fuels: While better data and reporting are essential, the overarching goal must remain clear – banks need to be pushed to commit to a just and equitable phase-out of fossil fuels. Civil society groups and advocacy tools, such as policy trackers, can help maintain pressure on financial institutions to adopt stricter fossil fuel policies.

- Drastically improve reporting standards for banks: Current reporting standards fall short, especially in relation to banks’ scope 3 emissions, which include financed emissions from clients in the fossil fuel sector. Mandatory scope 3 reporting is essential for holding banks accountable for the detrimental impacts of their investments. This should be enforced and unified through existing frameworks such as the Corporate Social Responsibility Directive (CSRD) int the EU, with benchmarks across the global financial sector.

- Prompt financial supervisors to request better data to assess climate risks: Misleading or incomplete data from banks limits the ability to accurately assess their true fossil fuel exposure and related climate risks. Supervisors, such as the European Central Bank, require improved reporting on fossil fuel finance, including detailed data on subsidiaries, to effectively manage transition risks and ensure alignment with the Paris Agreement.

This report is the latest in a series of papers by the Tax Justice Network aiming to strengthen the links between the tax justice and climate justice movements and equip campaigners with tax justice tools.

Introduction

To prevent and mitigate the most extreme climate crisis trajectory, we need nothing less than the root-and-branch reform of our economic systems. In recent years, the climate justice movement has secured some fiscal policy wins, like the creation of a Loss and Damage fund, meant to support those developing countries most vulnerable to the adverse effects of rising temperatures. However, the global financial system is still fundamentally at odds with climate goals, as it entrenches high-carbon development pathways, while failing to provide sufficient resources for climate adaptation.[2]

One reason for this misalignment is financial secrecy, which enables fossil fuel financing to flow amply but in opacity through secrecy jurisdictions. It thus drastically undermines efforts to enforce and improve environmental regulation in the fossil fuel industry, and the ceasing of funding fossil fuels altogether.

For decades, financial secrecy[3] has enabled the wealthiest interests to hide their assets from the rule of law. Whether it’s to abuse tax, launder dirty money or circumvent state sanctions, financial secrecy makes it possible to circumvent the laws and regulations governments put in place to protect peoples’ rights, livelihoods and safety.

As this report demonstrates, financial secrecy allows banks and fossil fuel companies to conceal their real fossil fuel exposure. We focus on the banking industry’s fossil fuel financing, revealing how long-standing offshore secrecy practices undermine the progress towards a greener financial system. We refer to this practice as “greenlaundering”. Alarmingly, financial secrecy enables an ecosystem of “planned ignorance”, allowing banks to claim progress away from fossil fuels towards sustainable investment practices.

The good news is that financial secrecy can be curtailed, including through reforms championed by the tax justice movement. We explore how the climate justice movement, including financial regulators focusing on green finance, can make use of these solutions to bring transparency and true accountability to fossil fuel financing.

Methodology and key concepts

In this chapter, we introduce key concepts used in our analysis that are helpful for understanding how secretive offshore finance works. We summarise the insights gained from analysing fossil fuel financing granted by the world’s 60 largest banks in the next chapter, with a particular focus on their link to secrecy jurisdictions. For methodological details, including on the underlying database and our analysis, please refer to the accompanying methodology note.

Please note that throughout this report we highlight structural features of the fossil fuel finance sector. We do not claim that any of the individual companies or banks named have set up or used any specific subsidiaries specifically for opacity purposes.

Secrecy jurisdictions

Secrecy jurisdictions are countries or territories that enable individuals or firms to hide their finances from the laws and regulations of other countries. They achieve this through a weak regulatory framework that allows for secrecy about critical details, such as the true owners (ie beneficial owners) of a company or the countries in which a company operates. Secrecy jurisdictions are often used to set up intricate company structures to obscure who is behind the company.

In this report, we determine the level of a country’s financial secrecy based on the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index[4], a detailed ranking of countries most complicit in helping individuals and entities hide their finances from the rule of law. In the index, each country is assigned a secrecy score ranging from 0, representing a fully transparent regulatory framework, to 100, representing the highest level of financial secrecy. In several figures, we colour-code financial secrecy levels like shown below.

Fossil fuel financing

We examine the involvement of the 60 largest banks in corporate lending and underwriting transactions for fossil fuel companies.

These fossil fuel companies are identified based on industry classifications available in financial databases, combined with research by urgewald for the Global Coal Exit List, the Global Oil and Gas Exit List.[5] Additional companies active in Liquefied Natural Gas were identified using the Global Energy Monitor and Enerdata.[6] The financing has been compiled in the Banking on Climate Chaos report by several climate organisations and covers financing between 2016 and 2023.[7]

It includes not only loans from banks but also revolving credit facilities – which are pre-approved amounts that companies can use if needed – as well as bonds, stocks underwritten by the banks, and other types of financing. All these instruments provide new capital, which allows fossil fuel companies to expand their activities, including fossil fuel-related activities.

Underwriting

Underwriting refers to the process where banks or financial institutions agree to purchase new stocks or bonds from a company (in this case, a fossil fuel company) and then sell them to investors. This service helps the company raise capital by ensuring that all the issued securities are sold in the market, thereby transferring the risk from the company to the bank. In return for this service and the associated risk, the bank earns an underwriting fee.

Underwriting bonds (and, to a lower extent, stocks) is a critical component of banks’ fossil fuel financing because it directly supports fossil fuel companies in raising capital. By underwriting bonds, banks enable these companies to secure the funds they need for their operations, including exploration, production, and development of fossil fuel resources. Even if the bank itself does not directly invest in fossil fuel projects, its role as an underwriter is essential in providing the necessary financial backing for companies’ operations.

Beneficial ownership

A beneficial owner is the real person who ultimately owns, controls or benefits from a company or legal vehicle. Companies must typically register the identities of their legal owners (which can be real people or other companies), but not necessarily their beneficial owners. In most cases, a company’s legal owner and beneficial owner are the same person but when they’re not, beneficial owners can hide behind legal owners, making it practically impossible to tell who is truly running and profiting from a company. This allows beneficial owners to abuse their tax responsibilities, break monopoly laws, get around international sanctions, launder money and funnel money into political processes – all while staying anonymous and out of the reach of the law.

Beneficial ownership is a crucial concept of oversight that allows looking through ownership chains that are often use to murky the entities and individuals that are steering and owning businesses. Secrecy jurisdictions often do not require the registration of beneficial owners, and they frequently do not mandate the registration of legal owners either.

Corporate groups and subsidiaries

Multinational corporations are typically composed of a group of different sub-firms, including one (ultimate) parent company that owns the entire group, several holding companies that control other companies and investments, and many subsidiaries. A subsidiary company is either partially or wholly owned by another company. Together, these firms are referred to as the multinational corporation’s corporate group, which can consist of hundreds of subsidiaries and entities.

The more subsidiaries and entities in a corporate group, the easier it is to foster opacity within the corporate group. Spreading a corporate group across several countries increases this opacity, as does setting up subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions. The average number of subsidiaries of banks in our sample is 32, while from the average number of subsidiaries of fossil fuel companies in our sample is 110.

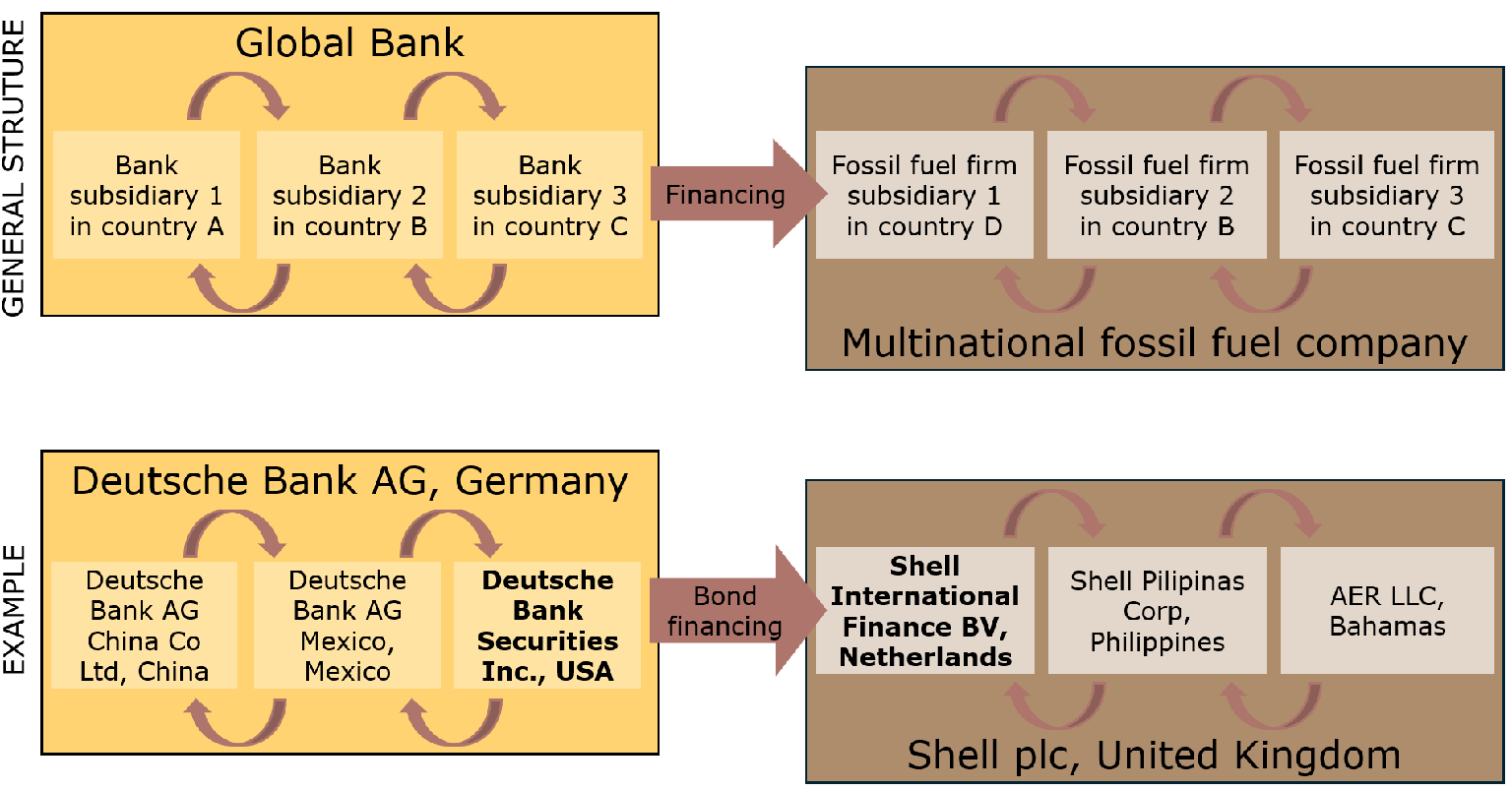

Figure 1 illustrates why the corporate group is such an important unit of analysis in fossil financing. The upper part of the figure shows how a global bank typically grants financing to a fossil fuel multinational. A financing agreement is made between the bank subsidiary acting as the lender and the fossil fuel subsidiary acting as the borrower. Such financing can be provided via:

- A loan, where the bank lends money to the firm, which then repays it with interest;

- A bond, where the bank provides financing in exchange for a bond document that it will typically sell to financial actors (the bank is then referred to as the “underwriter” of that bond); or

- A credit facility, where the bank promises to grant a loan of a certain amount whenever the fossil fuel multinational decides to use it (“draw on it”).

The lower part of Figure 1 provides an example of such financing. In this example, a bond was issued by the Netherlands-based Shell subsidiary, Shell International Finance B.V., and underwritten by the U.S.-based Deutsche Bank subsidiary, Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. However, the subsidiary receiving the financing – Shell International Finance B.V. in this case – is not the entity that will ultimately use the money, as explained in the next section.

Internal capital markets

Corporate groups, which consist of different subsidiaries under the same parent company, move their financing around within the multinational group using internal capital markets. Internal capital markets refer to how companies allocate their own financial resources internally to fund various projects, such as exploration, extraction, and production of fossil fuels, or to support related investments. This means that the financing granted to one subsidiary of the corporate group might eventually be used by another subsidiary.[8] In the example of Figure 1, the proceeds of the bond initially issued by Shell International Finance B.V., could be used by any other subsidiary of Shell, for example by the Philippines-based subsidiary Shell Pilipinas Corp.[9]

Internal capital markets are not only used by fossil fuel multinationals but also by the banks granting the financing. For Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. in the US, this means that other Deutsche Bank subsidiaries or the entire group could support the financing by providing preferential loans to subsidiaries within the same banking group.

A core problem of tracing fossil fuel financing is that it is nearly impossible to determine where each loan given to one fossil fuel subsidiary is eventually used. However, for financial subsidiaries like the example given of Shell, we can be certain that financing is passed over to other subsidiaries since the sole stated purpose of the financial subsidiary is to raise finance for the corporate group and pass it on to where it is needed most.

Findings: fossil fuel financing via secrecy jurisdictions

In the following section, we first examine how two prominent fossil companies – Aramco, the world’s largest oil company, and Glencore, the world’s largest coal producer and exporter – structure their financing and how this links to secrecy practices in different jurisdictions.

We then take a broader look and analyse general patterns of fossil fuel financing, investigating specifically whether bank subsidiaries in countries different from their parent company locations are systematically providing financing to fossil company subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions.

Example 1: Saudi Arabian Oil Group (Aramco)

Aramco, officially the Saudi Arabian Oil Group, is the national oil company of Saudi Arabia and the largest oil company in the world by market capitalisation.

Figure 2: How Saudi Aramco finances its activities

Figure 2 illustrates all subsidiaries that have received financing for Aramco’s corporate group in our analysis between 2016 and 2023. We highlight fossil subsidiaries in black, financial subsidiaries in gold, and subsidiaries from another industry in green. The arrow width shows the amount of financing subsidiaries pass to each other. As we cannot observe where the finances are eventually used, we direct all of them to the parent company or the company that probably re-allocates funds in our illustration.

Figure 2 illustrates that Aramco’s financing network spans several firms from different industries, many of them based in well-known secrecy jurisdictions.

Figure 3: The use of secrecy jurisdictions to channel Aramco’s financing

Figure 3 provides details on these jurisdictions and explores the implications and consequences of this financing structure. The figure colours each subsidiary according to the secrecy score of its host country according to the Financial Secrecy Index: blue indicates a low Secrecy Score, yellow a moderate score, orange and red a high score, and dark red a very high Secrecy Score. The different subsidiaries can be potentially pose transparency problems.

Aramco’s subsidiaries SABIC Capital B.V., SABIC Capital I B.V. and SABIC Capital II B.V. are all based in the Netherlands. The country has a secrecy score of 65/100 on the Financial Secrecy Index, due to the country’s lack of relevant transparency rules and its provision of incentives for shifting profits into the country.[10] Information on B.V.’s (private limited liability companies), the corporate form of SABIC Capital, is not freely available but can only be accessed for a fee after registering with Netherland’s corporate registry. Even the record obtained from the corporate registry often lacks basic information, such as income statements or cash flow statements – essential information to assess the financial position of a company.

Moreover, being based in the Netherlands allows SABIC Capital B.V. to avoid paying withholding taxes on interest payments or having to publish information about either the company’s beneficial nor its legal ownership.[11] As a result, the public might be unaware of the subsidiary’s role within the broader corporate group. While banks and auditors should have the tools to uncover these connections, the complexity and lack of public pressure provide them with a convenient explanation for “planned ignorance.”

In the example of SABIC Capital B.V., the secrecy is further complicated by the different industries involved in Aramco. The direct parent of SABIC Capital B.V., SABIC, operates in chemical activities, not fossil fuels, making it less obvious that SABIC is an Aramco subsidiary. Linking the Dutch-based SABIC Capital to Aramco is even more challenging as it requires first identifying SABIC’s parent company and then tracing it back to Aramco. This is a highly complex task when the firm in question does not need to maintain fully public accounts or present basic and free information about its ultimate beneficial owner.

SABIC Capital B.V.’s annual report shows how such opacity conceals the fossil nature of funds: SABIC’s auditing company states in SABIC’s annual report that “given the nature of SABIC Capital B.V.’s activities, the impact of climate change is not considered a key audit matter.” While potentially true for SABIC Capital B.V. or even for its direct parent SABIC, this is definitely not true for the company’s global ultimate owner, the largest oil company of the world.

The Cayman-based subsidiary SA GLOBAL Sukuk Ltd introduces additional secrecy into Aramco’s corporate structure. Based in a secrecy jurisdiction with a high secrecy score of 73/100[12], no public information can be found on SA Global Sukuk Ltd. This means that the public cannot even access basic financials, let alone information on legal or beneficial owners. Consequently, it would be difficult for a lending bank to establish SA Global Sukuk’s connection to Saudi Aramco – or, at the very least, it would be easy to disregard this connection.

This way of setting up and organising a corporate group is not unique to Aramco but serves as an illustrative example of what is likely common practice among fossil fuel companies and multinational corporations in general.

We contacted Aramco to provide them with an opportunity to respond to our report’s analysis. Aramco did not provide any feedback. Full documentation of our correspondence with the company is included in the accompanying methodology note.

Example 2: Glencore

We find a similar usage level of secrecy jurisdictions when looking at Glencore, one of the world’s largest coal producers and exporters. Figure 4 shows the financing structure of Glencore entities that have received financing according to the Banking on Climate Chaos report, with fossil subsidiaries marked in black and financial subsidiaries marked in gold. Again, we see a mixture of fossil and financial companies, many of them based in secrecy jurisdictions.

Figure 4: How Glencore finances its activities

Figure 5 illustrates how these secrecy jurisdictions can assist Glencore to hide obvious links to its fossil activity or to abuse tax. Again, each subsidiary is coloured based on its location’s secrecy score, with blue indicating a low secrecy score, yellow indicating a medium secrecy score, orange and red indicating a high score and dark red jurisdictions a very high score.

Figure 5: The use of secrecy jurisdictions to channel Glencore’s financing

Glencore’s headquarters, Glencore International AG, is registered in Baar, Switzerland. While Switzerland has a high financial secrecy score of 70/100, the municipality of Baar is particularly prominent for its financial privacy and harmful tax policies. Baar, located in the canton of Zug, offers very low tax rates and various incentives, making it a popular destination for multinational corporations seeking to underpay tax. Intra-company interest payments to Glencore International AG from other subsidiaries are subject to Swiss tax regulations, which can enable profit-shifting strategies within the corporate group.[13]

The financing for Glencore is channelled through its parent company, Glencore plc, which is incorporated in Jersey, a well-known offshore financial centre and tax haven. Jersey’s corporate laws allow for high levels of confidentiality, making it difficult to access detailed information about registered companies. Annual reports and comprehensive financial statements are not typically required to be publicly disclosed. Jersey’s harmful corporate tax rules, including no capital gains tax and very low corporate tax rates, makes it a popular jurisdiction for profit shifting. Intra-company interest payments to Glencore Finance Europe Ltd from other subsidiaries could be deducted against taxable profits made by these other subsidiaries, making it possible to shift profit within the corporate group.[14]

Additionally, Glencore Funding LLC is incorporated in Delaware, a renowned US corporate tax haven and secrecy jurisdiction. Delaware’s minimal reporting requirements restrict public access to comprehensive information, as the annual reports filed typically do not include detailed financial statements. Furthermore, Delaware does not tax revenues from intangible assets earned outside the state, making it an effective location for profit shifting. Intra-company interest payments from other subsidiaries could remain untaxed, making it possible to easily shift profit within the corporate group.[15]

We contacted Glencore to provide them with an opportunity to respond to our report’s analysis, including further examination of Glencore’s subsidiaries presented in the next section below. The company replied, stating that they raise debt finance through highly regulated bank or capital markets, with subsidiaries that transparently publish accounts for stakeholders such as banks, investors, and tax authorities. They emphasised that their consolidated debt position is publicly available and that accounting rules prevent them from concealing liabilities based on nationality or jurisdiction. Additionally, they affirmed their commitment to complying with tax laws and regulations, while maintaining transparent relationships with tax authorities, referring to their 2023 Payments to Governments report for further details. Unfortunately, the company was unwilling to share their country by country report, which could have provided additional clarity on the roles and activities of their various subsidiaries.[16] Our full correspondence with Glencore representatives is included in the accompanying methodology note.

The tip of the iceberg: what the data doesn’t tell us

While these firm structures seem sophisticated, Figures 2 to 5 only show a small subset of the actual corporate groups that Aramco and Glencore encompass. This is because even the Banking on Climate Chaos report might not cover all financing granted to the corporate group.

Figure 6 further estimates the extent of missing information for Glencore. It includes the six Glencore subsidiaries we previously identified and discussed. It then adds all Glencore subsidiaries available in the pay-to-access Orbis ownership database[17], which focuses on subsidiary structures. Instead of the previously identified six subsidiaries, Glencore has a total of 588 Glencore subsidiaries.[18] As we do not have specific information about these subsidiaries beyond their names, we cannot determine their exact roles within the corporate group. However, even without further details, it is highly likely that at least some subsidiaries received loans or other financing from the 60 largest banks. Judging by their names, several subsidiaries appear to have active financing roles, such as Singpac Investment Holding PTE LTD, Silena Finance B.V., or Perfetto Investment B.V.. However, we have no way of determining the specific role each subsidiary plays in internal and external financing, or in fossil fuel expansion. This further illustrates how complex and opaque corporate structures, combined with insufficient transparency regulations, make it impossible to fully trace fossil financing activities and hold banks and companies accountable for their actions.

Figure 6: Glencore subsidiaries that are not observable in Banking on Climate Chaos

These limited insights do not allow us to draw definitive conclusions about Glencore’s actual activities. Simply observing the location of various subsidiaries provides no proof, nor even a strong indication, of how the company is using these jurisdictions. While the presence of subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions could facilitate profit shifting to minimise tax obligations, we lack sufficient information to determine whether Glencore engages in such practices. It is also possible that its economic activities in each jurisdiction are aligned with the profits reported there. One key transparency tool that could enable researchers, as well as the public, to evaluate this is public country by country reporting. A country by country report provides an overview of a multinational corporation’s activities in each country where it operates, including profits reported, the number of employees, assets located there, and taxes paid on those profits.

As a multinational mining company, Glencore is required to publish only a very limited version of this report, specifically detailing payments made to governments related to its extractive activities.[19] However, in this public report, neither Jersey nor Switzerland are mentioned, leaving the public clueless about the profits Glencore reports in these jurisdictions and the corresponding taxes it pays. In addition to this public report, Glencore is required to submit a more comprehensive country by country report to the Swiss tax authorities, which includes information on economic activities and taxes paid across jurisdictions.[20] Unfortunately, this report is not made public, and Glencore declined to share it with us for research purposes. [21]

This lack of transparency highlights how secretive corporate structures hinder the ability of the public to verify whether companies are fulfilling their obligations, both in terms of tax compliance and climate responsibilities. It also makes it difficult to hold fossil fuel companies and their financial backers accountable for potential misconduct, as any wrongdoing can easily be concealed from public scrutiny.

These structures are by no means unique to Glencore. As with our deep dive into Aramco, Glencore’s financing structures serve as illustrative examples of common practices by multinational corporations related to fossil fuel financing.

Again, our full correspondence with Glencore representatives is included in the accompanying methodology note.

The larger pattern

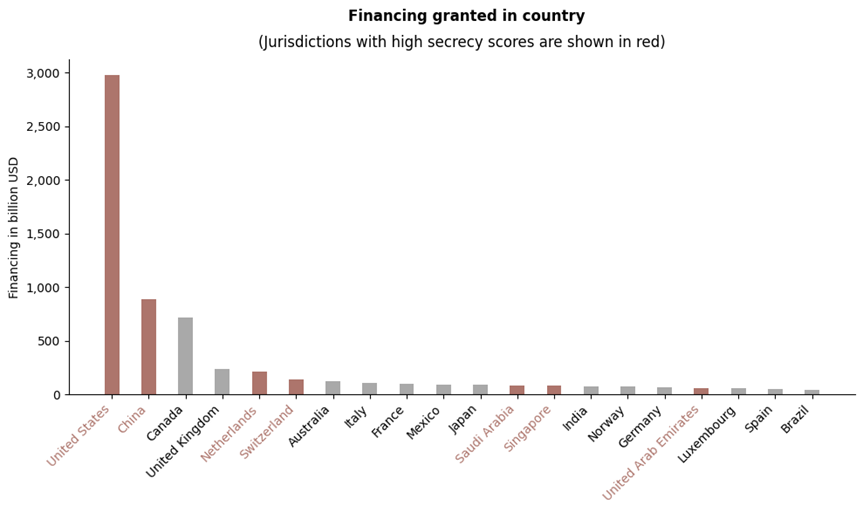

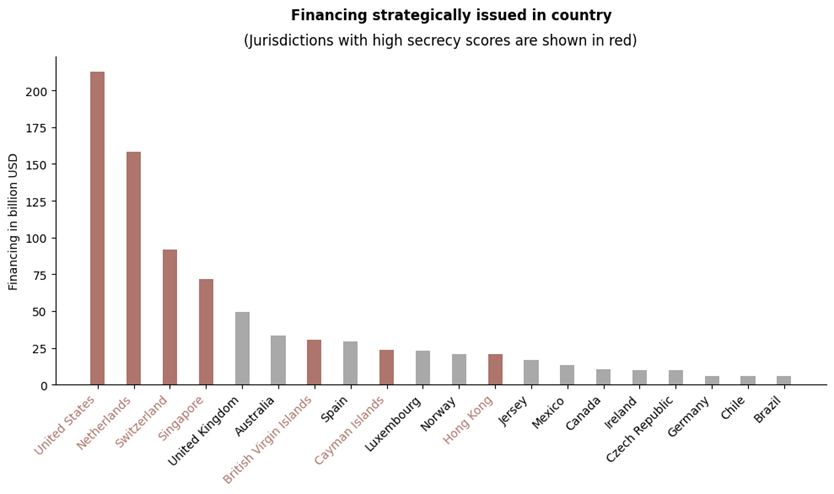

To investigate this common practice and see whether fossil fuel financing is systematically received through secrecy jurisdictions, Figure 7 shows the 20 countries that receive the most fossil fuel financing according to the Banking on Climate Chaos 2024 report.

About US$2.97 trillion – more than a 40 per cent of all financing – goes to fossil subsidiaries located in the US. China and Canada rank second and third, with Chinese-based fossil subsidiaries receiving about US$888 billion and Canadian-based firms about US$718 billion. Figure 7 highlights high-secrecy jurisdictions in red. We define a high-secrecy jurisdiction as a country with a secrecy score higher than 60% of our sample countries, which translates to a score of 63.8/100 or higher.[22]

Figure 7 reveals that several high-secrecy jurisdictions are among the countries receiving the highest volume of fossil fuel financing. In total, secrecy jurisdictions receive more than 68% of all fossil fuel financing.

The high volume of financing going to these jurisdictions could be due to factors other than their secrecy: larger countries or economies likely receive more financing of any kind. Equally, if fossil fuel financing is issued where fossil activity takes place, fossil fuel producers would logically attract a higher loan volume. In the following section, we demonstrate that even when accounting for these factors, secrecy jurisdictions attract an abnormally high volume of fossil funds.

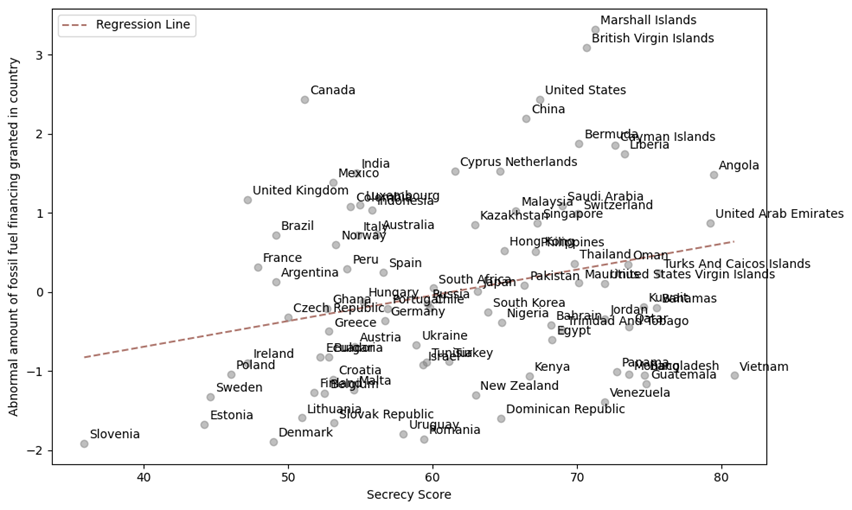

To establish this relationship, we first calculate the abnormal volume of fossil fuel financing received. We define the abnormal volume of fossil financing received as the difference between the fossil fuel financing expected given a country’s population and GDP, and the fossil financing actually received by the country. Figure 8 shows this abnormal volume of fossil fuel financing compared to their secrecy score on the Financial Secrecy Index. Jurisdictions whose laws and regulations permit a high level of financial secrecy attract considerably higher volumes of fossil fuel financing than would be proportional to the size of their economy and their population.

To determine if there is a systematic link between secrecy and abnormal fossil financing, we regress abnormal fossil financing on the secrecy score. The relationship between countries’ abnormal fossil financing and their secrecy score, illustrated by the red line in Figure 8, is statistically significant, with a beta coefficient of 0.27 and a p-value of 0.012.[23] This indicates that, indeed, high-secrecy countries do receive systematically more fossil fuel financing as we should expect, based on economic factors.

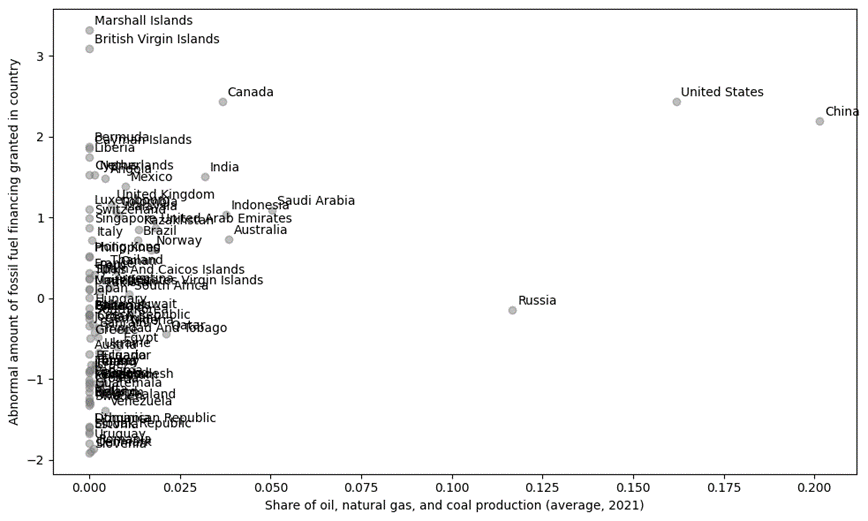

Interestingly, we do not see a similar relationship between abnormal fossil fuel financing and fossil-producing countries in Figure 9. The figure examines whether the abnormal volume of fossil fuel financing received can be explained by actual economic needs related to fossil energy production, specifically the amount of fossil activities occurring in the country of interest. The figure plots a country’s share of fossil production, averaged over oil, gas, and coal production from BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2022 (x-axis)[24], against its abnormal volume of fossil fuel financing received (y-axis).

Despite the presence of clear outliers, such as the United States, Russia, and China—where high fossil fuel financing inflows can be attributed to their significant fossil fuel activity—there is no systematic link between the two variables. This suggests that actual fossil activities do not account for the abnormal fossil fuel financing received by secrecy jurisdictions. [25] In other words, fossil-producing countries’ greater need for and use of fossil fuel financing does not result in abnormally high volumes of such financing.

Taken together, these findings suggest that countries with higher secrecy scores attract more fossil fuel financing compared to countries of similar size and economic activity with lower secrecy scores. Moreover, this relationship is not due to higher fossil fuel production. This indicates that the preference for secrecy jurisdictions is likely driven by the desire to exploit regulatory loopholes and maintain financial opacity, rather than by the actual need for fossil fuel activities.

The abnormally high amount of fossil fuel financing in secrecy jurisdictions that we observe is linked to the corporate structure of fossil fuel companies.

First, parent companies are often located in secrecy jurisdictions. As previously shown, Glencore’s parent company is registered in Jersey. However, for most firms registered in secrecy jurisdictions, this is not where they conduct their actual business activity. For instance, Glencore’s head office is not in Jersey, but in Switzerland. Similarly, many of the largest Chinese oil, coal and gas companies are officially based in the tax haven Hong Kong.

Second, fossil fuel companies strategically locate subsidiaries meant to raise finance in secrecy jurisdictions. Indeed, most fossil fuel companies have several subsidiaries specifically dedicated to raising funds and located in a secrecy jurisdiction. For instance, the sole purpose of Shell’s subsidiary, Shell Finance B.V., located in the Netherlands, is to raise funds and transmit them to the overall company. Similarly, most large Chinese oil, gas and coal firms – which are often officially registered in Hong Kong – tend to have financial subsidiaries in the British Virgin Islands or Bermuda. These subsidiaries are designed to raise private funds and channel them into new investments primarily based in China.

The calculated setting up of financing subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions is also evident in the aggregate data. To illustrate this, Figure 10 aggregates all financing received in a country different from the parent company’s country. By excluding financing issued in a location simply because the parent company is based there, we can estimate the amount of financing strategically channelled through secrecy jurisdictions. As in Figure 7, countries with a high secrecy score are coloured in red. As before, we define a high-secrecy jurisdiction as a jurisdiction with a score of higher than 60% of our sample countries, which translates to a score of 63.8/100 or higher.

Figure 10 shows that secrecy jurisdictions are widely used for channelling fossil fuel financing. The United States and the Netherlands stand out as key locations for raising funds that are likely directed elsewhere, potentially to finance fossil fuel expansion. Switzerland and Singapore are also popular destinations for financing that is ultimately used in other locations. Interestingly, different secrecy jurisdictions are popular for different activities and among different types of fossil fuel companies: Western firms tend to use the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Luxembourg to channel funding, while Russian firms have historically raised their financing via the UK and Cyprus. Chinese firms predominantly rely on Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands, and the British Virgin Islands, in addition to the funds Chinese subsidiaries receive directly. Much of the US-based activity occurs within the US, with US-based parents having their financing subsidiaries in domestic secrecy jurisdictions, most prominently in Delaware.[26]

We now shift our attention to the banks who grant financing. To track how fossil fuel financing from different banks flows through secrecy jurisdictions, we analyse instances where the issuance of funds occurs in locations different from the parent company’s country for each bank. Figure 11 highlights the jurisdictions where fossil fuel subsidiaries receiving financing from Citigroup are located (middle part of the chart), and where the financing ultimately ends up (i.e. where their parent companies are based, right side of the chart). Jurisdictions and associated flows are colour-coded based on their level of financial secrecy, ranging from blue for low secrecy, yellow for moderate secrecy, to red for high secrecy.

In the case of Citi’s fossil fuel financing, the bank itself is located in a high-secrecy jurisdiction, as indicated by the red colouring. Key conduit jurisdictions include the United States, the Netherlands, the Cayman Islands, the UK, and the British Virgin Islands. The primary destination jurisdictions for these flows are the UK, the Netherlands, Canada, and Bermuda. As seen with other banks in the analysis, both the funding and its eventual destination often involve high-secrecy jurisdictions, which are frequently chosen as locations for financing subsidiaries as well as headquarters for fossil fuel companies.

When we reached out for feedback, Citi expressed concerns about our methodology and requested a meeting to discuss the report. Citi did not respond to our invitations to a video call. Our full correspondence with Citigroup is available in the accompanying methodology note.

Figure 11: Destination and transit of the largest banks’ fossil fuel financing

Please choose your bank of interest in the dropdown menu.

Discussion: how fossil fuel firms and banks benefit

In the following chapter, we provide evidence of how the strategies described so far enable fossil fuel companies to obtain better financing conditions, and banks to circumvent public and regulatory scrutiny. The use of offshore financial secrecy makes it possible for both fossil companies and banks to hide fossil investments and financing. We refer to this phenomenon as “greenlaundering”.

While fossil fuel companies and their creditors share similar incentives with other large multinationals, they likely gain specific advantages in the context of fossil fuel loans. By concealing the true purpose of their loans, fossil fuel companies can avoid exclusion or restrictions from banks that claim to adhere to sustainability standards or face stricter regulatory requirements when funding climate-destructive businesses. Consequently, by masking their fossil fuel-related activities, these companies can secure more favourable financing conditions, including larger loan amounts, longer repayment periods and lower interest rates.

Planned ignorance about whom they are financing, combined with the low risk of such financing becoming public knowledge, allows banks to continue greenwashing their public image without cutting ties to profitable fossil customers or stepping away from otherwise lucrative deals.

In the following section, we first document how the fossil fuel exclusion policies of the largest global banks contain loopholes that allow indirect fossil fuel financing via subsidiaries, such as financing through secrecy jurisdictions. We provide examples demonstrating how these loopholes have enabled the largest expansionary fossil fuel companies to continue to receiving financing, despite appearing to be excluded by these policies. We also show how such unclear definitions bias banks’ sustainability reporting by contradicting banks’ self-reported fossil exposures to what we see in the Banking on Climate Chaos report. Finally, we document that fossil fuel financing granted in more secretive countries is indeed associated with better financing conditions, particularly with lower interest rates.

Circumventing banks’ exclusion policies

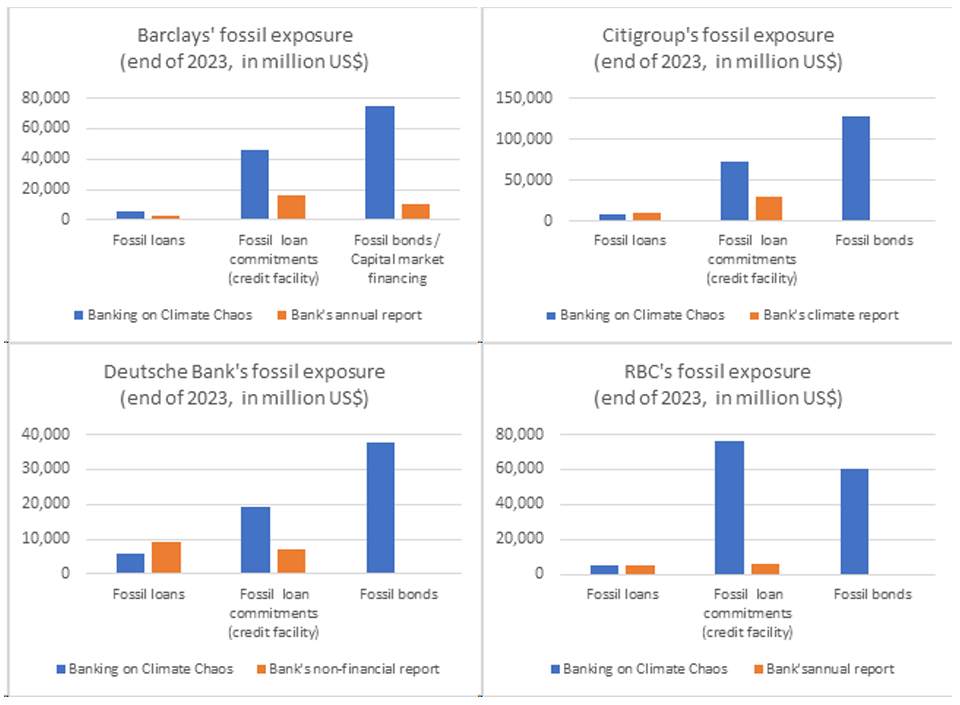

Responding to increasing public and regulatory pressure to divest from polluting industries, several banks have issued exclusion policies, claiming they will no longer fund fossil fuel activities, particularly expansionary ones. Such claims have been prominently advertised on banks’ websites and sustainability reports. In the following section, we assess whether the exclusion policies of six major banks encompass all types of fossil fuel financing, regardless of how the financing is strategically channelled. We selected these banks to represent the largest global banks and various regions where exclusion policies are relevant.

Table 1 in shows some of the most important fossil fuel exclusion policies of these banks and specifies how narrowly or widely the policies target financing recipients. This targeting can be categorised into three levels: the project level, the subsidiary level, or the corporate group level.[27]

Of the six banks, only HSBC explicitly clarifies that its exclusion policies are assessed at the corporate group level, at least for some of its policies. Barclays also uses a group-level assessment for some policies but limits its energy policies to groups that derive at least 20% of their revenue from upstream oil and gas activities or to groups classified as super majors or major integrated oil and gas companies, which makes financing to a significant portion of diversified companies with substantial fossil fuel operations possible under the role. Most of the other banks primarily exclude only project financing or limit their exclusions to the subsidiary level.[28] Even more problematically, some policies apply only when specific conditions are met for both the subsidiary or project and the corporate group. For example, the policy is effective only if the corporate group meets a certain fossil fuel revenue threshold and the subsidiary or project fits a particular profile, rendering the policy highly ineffective.

This is surprising, given that banks are aware of multinational corporations’ use of internal capital markets. Indeed, banks usually consider the entire corporate group when granting a loan, rather than simply relying on one single subsidiary. For instance, the parent subsidiary will be held accountable if the borrowing subsidiary does not repay the loan, and loans will be granted based on an assessment of the financial conditions of the group, rather than just the subsidiary. Consequently, banks should understand that not explicitly excluding such subsidiaries in their exclusion policies leaves open a window for fossil fuel financing.

When we requested clarifications on banks’ acknowledgement of subsidiary structures in exclusion policies, Barclays, BNP Paribas, and Deutsche Bank provided additional details regarding their policies, their scope of applicability, and highlighted measures implemented to ensure the robustness of these policies. We have incorporated their responses in Table 1. BNP Paribas highlighted that their oil and gas policy “applies strict commitment to corporate [financing]”.[29] All correspondence with the banks is included in the accompanying methodology note. Table 1: How bank exclusion policies consider fossil fuel companies’ subsidiary structures

Note: This table only include exclusion policies (no general reduction targets) and policies that are already implemented (not the ones planned for the future). Rather than providing an encompassing overview of all policies, it is meant to illustrate on which level most policies apply. The table is also not meant to assess or judge bank’s exclusion policies in detail, but only focuses on their level of application in the context of financing through internal capital markets. For a detailed assessment on the quality of banks’ exclusion policies, see the Coal Policy Tracker and the Oil and Gas Policy Tracker provided by Reclaim Finance.

Banks fund fossil fuel expansion despite exclusion policies

Unambitious or vague exclusion policies—both in terms of subsidiary coverage and regarding the types of financing or definitions of fossil fuel firms—enable the continuation of funding that banks give the impression they have stopped. Meanwhile, fossil fuel companies continue to receive financing from the largest global banks, despite these banks’ public claims to transition financing away from the fossil fuel industry.

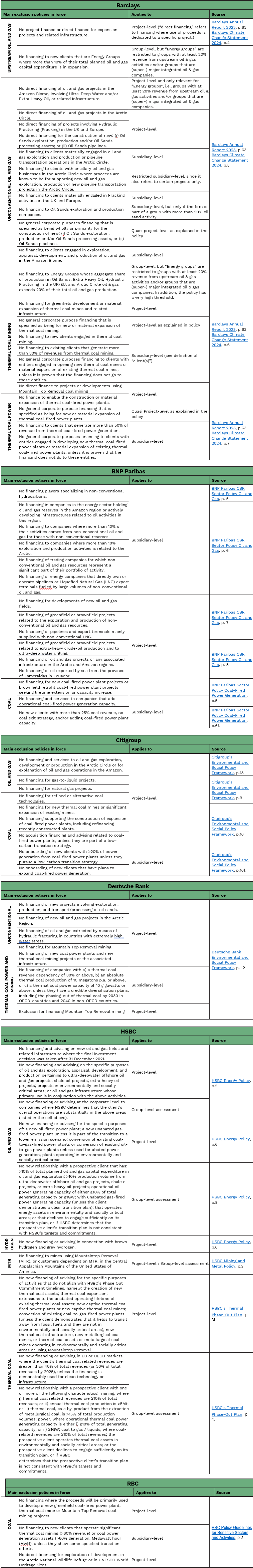

An example of this is shown in Figure 12. It contrasts BNP Paribas’ climate commitments in its 2022 climate report (left panel in green) with some examples of the bank’s fossil fuel financing in 2023 (right panel in red). According to its 2022 climate report[30], between 2016 and 2022, the bank committed to:

- Stop oil project financing (2016)

- Cease business with shale oil and gas and tar sand companies (2017)

- Cease financing in the thermal coal sector value chain in the EU and in OECD countries by 2030, and in the rest of the world by 2040 (2020)

- Reduce its financing to upstream oil and gas by 10% between 2020 and 2025 (2021)

- Restrict its support to energy companies involved in the Arctic and Amazon regions (2022)

To verify BNP Paribas’ compliance with these commitments, we examined fossil-related financing that was granted by the bank in 2023, a point at which all these policies should have been in place. Figure 12 presents a selection of such financing in the right (red) panel.[31]

We begin with a bond underwritten for Japan-based Mitsubishi Corp in 2023, granted via the BNP Paribas U.S. subsidiary BNP Paribas Securities Corp as part of a larger consortium. Since 43% of Mitsubishi Corp’s 79 million barrels of oil equivalent (mmboe) oil and gas production is based on fracking, providing funding to this subsidiary seems at odds with BNP Paribas’ 2017 commitment to cease business with shale oil and gas. Despite this, the bond provides Mitsubishi Corp, which invested US$70 million to expand fossil activities in Australia, Brunei, Canada, China, Gabon, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Russia, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela in the three years preceding the bond, with an additional US$500 million over the next five years. The bond proceeds are intended “for general corporate purposes,” according to the bond issuance documents, which does not bind the firm to a specific use.[32]

Note: The commitments in green are directly taken from BNP Paribas’ 2022 climate report. The examples of BNP Paribas’ financing come from the Banking on Climate Chaos report and from cbonds for the bond of Mitsubishi Corp. Information about the fossil companies’ business is from the Global Oil and Gas Exit List 2023 and the Global Coal Exit List 2023, both provided by urgewald.

A second example involves the financing of oil and gas, where project financing has been banned since 2016, and BNP Paribas committed in 2021 to reduce its upstream oil and gas financing, according to its own climate report. However, one of the deals that raises questions about the seriousness with which BNP is adhering to these commitments is the bank’s involvement in corporate loans totaling US$2.5 billion to UAE-based Mubadala Treasury Holding, granted by BNP’s Bahrain-based subsidiary in collaboration with other banks. Mubadala Treasury Holding is a subsidiary of the UAE’s sovereign wealth fund, Mubadala Investment Company, which is also the 100% parent of the upstream oil and gas company Mubadala Energy.

Mubadala Energy has short-term plans to expand its resources by 25 mmboe in Egypt, Indonesia, Israel, Malaysia, Russia, and Venezuela – 83% of which are considered unconventional. Over the three years preceding the loan, Mubadala Energy invested US$66 million in the exploration of new fossil resources – all exploration that is incompatible with the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario. The loan, granted in 2023 and maturing in 2028, provides funding for an additional five years. While the loan is not officially designated for oil projects, there is no indication that such use of the proceeds is prohibited from being passed from Mubadala Investment Company to Mubadala Energy.[33]

The bank’s promise to restrict support for energy companies involved in the Arctic and Amazon regions also appears questionable, given the US$300 million credit line granted to the Norway-based company Aker Solutions in 2023, which remains open until 2028, again as part of a consortium. Aker Solutions is a subsidiary of Aker ASA, a company heavily involved in the oil business, which “has grown from practically zero to 55 percent” of Aker’s value over the last 15 years, as Aker ASA proudly states in its 2022 Annual Report. Aker’s oil subsidiary, Aker BP, had invested nearly US$1.5 billion in the exploration of new resources over the previous three years, with its Arctic production accounting for 13% of total production. This funding seems at odds with BNP Paribas’ commitment to cease support for such environmentally sensitive areas.

BNP Paribas—and other banks confronted with the question of how such financing aligns with their self-defined policies—will likely provide clear reasoning as to why each instance of funding does not officially violate their exclusion policies. Asked about the financing, BNP Paribas firstly referred to banking confidentiality rules. The bank then stated that “in the examples of transactions [given in Figure 13 of this report] are referring to, there appear to be confusion around whether these legal entities you specifically mentioned are actually active in the exploration and production of fossil fuels, and what their respective position is within the diversified groups.”[34] The latter point – the relevance of subsidiary’s position within a diversified group – is to the core of our critique: given that fossil fuel firms are expected to use internal capital markets and nothing seems to prohibit them from doing so in the analysed deals, their position within a group should not matter for exclusion policies.

Other frequent explanations of banks when asked about specific financing that seems to clash with their policies include not being the lead arranger of a deal, following different definitions of fossil fuel activities compared to our sources, using complex calculations of thresholds, or disregarding the subsidiary structures of corporate groups.[35] However, all these examples demonstrate how banks do not commit to the spirit of their own exclusion policies, even if they technically adhere to them. As a result, fossil fuel companies continue to secure financing, potentially without even having to pay a premium, with the support of banks’ planned ignorance and partly enabled by secrecy jurisdictions.

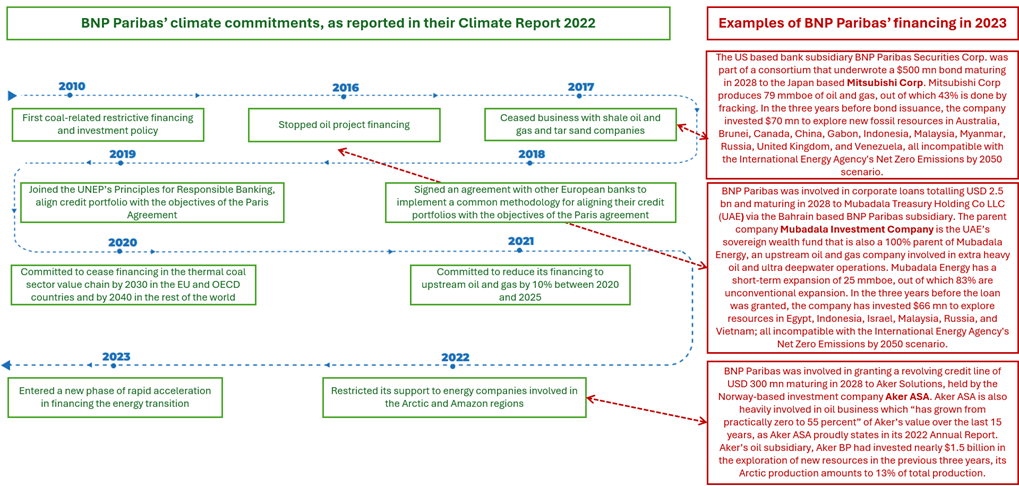

Banks understate their fossil exposures in sustainability reporting

When banks fail to classify fossil fuel loans accurately, it should result in overly optimistic sustainability reporting. To check whether this is the case, Figure 13 compares what large banks report as their fossil exposure in their sustainability or annual reports to the exposure observed in the Banking on Climate Chaos report.[36]

Figure 13: Banks’ fossil exposure in the Banking on Climate Chaos report and banks’ sustainability reports, climate reports, and annual reports

Note: For details regarding the exact data sources and methodology used to calculate exposures, we refer to the report’s methodology note.

We find a significant mismatch between banks’ claimed fossil exposures and the figures from the Banking on Climate Chaos report. This discrepancy arises from banks’ generous definitions of what constitutes fossil-related activities, their partly exclusion of bond issuance from reporting, and their failure to account for the entire corporate group in fossil fuel financing.[37] The discrepancy is even more pronounced considering the highly conservative nature of Banking on Climate Chaos. As the report is based on syndicated lending and underwriting data, it should only cover a fraction of banks’ total exposure.[38]

When requesting feedback on Figure 13, Barclays, BNP Paribas, and Deutsche Bank pointed us to additional reporting on capital market financing (Barclays) and coal exposure (Deutsche Bank). Barclays suggested that differences in methodologies for estimating fossil fuel exposures may explain the discrepancies noted in Figure 13. All correspondence with the banks is included in the accompanying methodology note.

In addition to the lack of clarity about banks’ dealings with fossil fuel company subsidiaries, their own subsidiaries in secrecy jurisdictions could also be used to reduce reporting obligations. This issue can be particularly significant when reporting on sustainable finance to financial authorities. Officially, most sustainable finance regulations, such as the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, apply to the entire banking group. However, only parts of the banking group are under the direct supervision of the regulator enforcing these regulations.

This means, for instance, that while Deutsche Bank Germany must report to the German central bank hosting the credit registry any loan granted by itself or by its EU-based subsidiaries to a fossil fuel company, any loans granted by its US-based subsidiaries, such as Deutsche Bank Securities Inc., are not reported.

It is therefore possible that EU financial authorities may only be aware of parts of banks’ fossil exposure, even though environmental regulation officially applies to banks’ total exposure as corporate groups, including non-EU subsidiaries. This greenlaundering loophole makes it possible for banks to continue financing fossil fuel activities while publicly greening their image through various commitments and initiatives.

Potential misrepresentations of fossil fuel exposures have two critical implications. First, if financial institutions were to report inaccurate figures, they would be in violation of sustainable finance regulations, such as the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) or the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which mandate transparency on environmental impacts, including fossil fuel exposure. Second, inaccurate or overly optimistic reporting of fossil fuel exposures suggests that banks are not appropriately assessing their climate-related risks. This failure to accurately assess risks means financial institutions would not meet the expectations for climate risk management set by financial regulators, such as the European Central Bank, which supervises large EU-based institutions.[39]

Secrecy jurisdictions are linked to lower fossil fuel financing costs

Does all this potential for obfuscation come with clear financial benefits? To explore this, we investigate the relationship between financial secrecy and the interest paid on loans or the coupon paid on bonds, which is the interest the bondholder receives.

We found a highly significant relationship when investigating all financing for which we know interest rates. If we compare loans and bonds granted in a country with a secrecy score of 25 (like Slovenia) to loans and bonds granted in a country with a secrecy score of 70 (like Switzerland), the average interest rate is one percentage point lower in the more secretive country.

A second indication of financial benefits from the strategic structuring of their financing arises from the observation that the stated use of proceeds for most financing is often very vague, such as for “general corporate purposes,” “refinancing” or “working capital.” One potential strategy available to fossil fuel companies is to label and promote investments in future-oriented projects as “Green Bonds” to secure better conditions, while using secretive structures to finance other ongoing environmentally harmful projects under generic, unsuspecting labels like “general corporate purposes.” This strategy allows a fossil fuel company to keep public and regulatory attention focused on the visible Green Bonds while diverting attention away from substantial “general” funds.

For example, French-headquartered energy giant Engie has issued Green Bonds specifically dedicated to transforming the company into a future-oriented business. Since 2014, Engie’s Green Bond issuance has reached €20.89 billion by the end of 2023, making it “one of the leading corporate issuers in the Green Bonds market,” as the company proudly states on its website.[40]

However, during the shorter time frame between 2017 and 2023 that we can observe in the Banking on Climate Chaos report, Engie’s bond issuance excluding Green Bonds amounted to about US$60 billion (approximately €55 billion). This is consistent with the fact that the company’s fossil fuel share of revenues still exceeded 50% in 2022.[41] In total, the Engie group received more than US$500 billion in financing over these six years. None of this financing is officially dedicated to fossil fuel projects. Instead, it officially serves to finance “general corporate purposes,” “refinance” or “repay selling shareholders,” with no indication that banks would prohibit Engie from using these funds for their fossil fuel business.

Asked for their feedback, Engie stated that their green bonds, including hybrids, are issued under a green financing framework verified by Moody’s, which excludes any fossil fuel investments. They also noted that annual reporting is available in their Universal Registration Document and on their Group website. For our full correspondence with Engie, please refer to the accompanying methodology note.

As long as a fossil fuel company can issue Green Bonds and banks’ Green Bond standards do not consider a corporate group’s entire business, fossil fuel companies can easily structure their financing to bundle all their sustainable activities into popular and inexpensive Green Bonds, advertise these bonds aggressively, and subsume the rest under “general purpose financing.”

What “greenlaundering” means for climate justice

Greenwashing is a well-known term that refers to visible forms of advertising that deceptively uses green PR and marketing to persuade the public that a company or its products are environmentally friendly. Greenlaundering involves the use financial secrecy and secrecy jurisdictions to obfuscate banks’ and fossil fuel companies’ real, fossil fuel exposure from the public and regulators.

Greenlaundering enables banks and fossil companies to at least partially circumvent some of the pressure to divest from fossil fuels fought for by the climate justice movement. In the process, it undermines sustainable finance regulators taking aim at the entirety of global banks’ business, including the activities of all subsidiaries. That so much of fossil fuel financing flows through secrecy jurisdictions makes it hard to enforce and improve these regulations. For instance, the European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) or the European Sustainability Finance Disclosure Regulation set goals for banks entire lending book – not only for EU-based subsidiaries. But European regulators only have access to the credit register covering financing granted by EU-based subsidiaries of banks, and cannot observe the activity happening in other countries. This problem is particularly pronounced for subsidiaries that do not reveal sufficient public information, such as those based in secrecy jurisdictions.

Greenlaundering also misleads and harms civil society, researchers and activists. This is because the systematic obfuscation of financing information makes it hard to grasp, quantify, communicate and mobilise in favour of regulatory policies and the general call to divest, since the real scale of fossil fuel exposure remains hidden. This lack of transparency therefore weakens the ground for climate advocacy in the sense that the goalposts for the climate justice movement about the financing of fossil fuel are constrained by limited financing information that is publicly available. The practice thus helps stifle radical climate action and erodes the already severely fractured sense of trust citizens have in governments acting in the interest of the many, not the few. It is also deeply uncompetitive: the promise of green finance pursued by some competing financial institutions and businesses breaks down when green and brown financing cannot effectively be distinguished.

How to dispel the hall of mirrors: policy recommendations to bring an end to planned ignorance

Negotiate transparency rules at the UN

Financial secrecy is a global problem in need of multilateral cooperation. By design, financial secrecy makes it possible to evade the rule of law elsewhere – that is, to evade other countries’ laws and regulations, and even international law. Greenlaundering and its role in undermining transparency in fossil fuel financing shows once more that effective multilateral coordination is needed if the global financial system is to play a positive role in achieving climate goals. This coordination can only be effective if it is inclusive and transparent at the highest level of governance, allowing citizens to hold governments accountable. Any efforts to reduce financial secrecy must not occur behind closed doors with privileged access for select countries and stakeholders.

The recent agreement to establish a UN Tax Convention[42] marks a significant shift towards transparent and accountable multilateral coordination about tax and transparency measures. For the first time, the creation of a global transparency and accountability framework is being negotiated openly and democratically, moving away from the historically exclusive and opaque OECD-led negotiations on global tax policies. Supporting this process towards a comprehensive framework convention is crucial not only for advocates of democracy, accountability and tax justice, but also to ensure the benefits of tax reform extend to the climate justice movement. The framework would allow the bridging of a critical gap at the highest level of governance: that between international tax negotiations and international climate negotiations. This bridge is sorely needed to mobilise the power of tax to address the challenges of the climate crisis.

Unmask polluters through comprehensive beneficial ownership transparency

Beneficial ownership transparency means identifying the individuals who ultimately own, control or benefit from legal vehicles such as companies, trusts or foundations – including fossil fuel companies and banks. As such, it is also a powerful tax justice policy for bringing transparency to the secrecy of fossil fuel financing. If beneficial ownership transparency is established and publicly accessible, it becomes clear which firm is behind which entity, on top of revealing who owns the most polluting assets and investments[43]. Consequently, fossil fuel companies would no longer be able to channel financing through subsidiaries with the same opacity and ease. Comprehensible and accessible beneficial ownership transparency would also lay the foundation for dismantling planned ignorance as banks could no longer feign ignorance about using fossil fuel subsidiaries in the usual manner.

If implemented well, this type of transparency reform[44] could both expose unreported fossil investments and bring the rule of law to bear on the extreme wealth of fossil fuel company owners – two essential steps to curbing financial secrecy, and with it, extreme wealth and emissions inequalities.

Improve public country by country reporting for corporations

Public country by country reporting is another transparency measure and requires multinational groups to disclose their economic activities on a country by country basis. Specifically, it mandates that multinationals report the number of employees, assets, reported profits and taxes paid in each country they operate in. This measure helps identify where multinationals strategically report profits and manipulate tax payments. In the context of opaque fossil fuel financing, it offers additional benefits: it can reveal where fossil fuel companies have secured financing without having much other activity. For example, detailed country by country data would reveal financial and holding companies based in secrecy jurisdictions, whose main purpose is to reduce lending costs. This could expose countries with no employees but significant financial assets. Therefore, stronger country by country reporting standards could help uncover the use of secrecy jurisdictions for fossil fuel financing and reduce “greenlaundering.”

Importantly, there are certain public country by country reporting standards in force for the fossil fuel sector in some countries, including in the EU[45]. These standards are insufficient, as existing regimes are typically based on EITI information standards for the reporting by governments of payments received by the extractives industry[46] and lack critical financial information needed to reduce greenlaundering, including on profits/losses before tax and interests paid to third party lenders like banks.[47] They are also subject to lobbying by fossil fuel giants. For example, the United States’ planned regime for public reporting by the extractive industry was suspended under pressure from companies including Exxon and Chevron[48], and has only recently entered into force, with the first public reports of US-based oil companies due soon.

Pressure banks to phase out investments in dirty fossil fuels

While our analysis points to the importance of better data and proposes a range of fine-grained technical and specialised governance recommendations, it is important to not lose sight of the bigger goal: the pressure on financial institutions to commit to a swift, just and equitable fossil fuel phase out must be maintained. Unmasking the web of financial secrecy that enables banks and fossil fuel companies to conceal their real fossil fuel exposure must happen in service of this wider goal, not as a goal in itself.

Multiple civil society and advocacy groups work in alliances to maintain pressure on this fossil fuel exit. Financial institutions must continuously be driven to adopt best practice fossil fuel policies, and many existing campaigning and advocacy tools like the Coal Policy Tracker and Oil and Gas Policy Tracker[49] are readily available to highlight their lagging commitments. Under pressure, robust fossil fuel policies would aim to close the loopholes we previously identified, including on subsidiaries. Existing financial institution alliances such as the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero and the Net Zero Banking Alliance should be the target of some of this pressure to ensure they set strict guidance and standards for their members to unify progress.

Drastically improve reporting standards for banks

As previously discussed, most global banks set out climate change goals in their sustainability reports, including a commitment to Net Zero. Yet very few have specific policies set to meet those targets.[50] The success of any divestment campaign relies heavily on ambitious and unified reporting standards that disclose fully and transparently all facilitated emissions banks are responsible for. These standards are missing.

The biggest gap in current reporting standards are binding obligations for all banks to report scope 3 emissions. In contrast to scope 1 and scope 2 emissions, which aim to capture a company’s own direct and indirect emissions, arising for example from burning fuels and energy use in the creation of the goods and services it sells – and which most large corporate entities do report – scope 3 emissions are created by a business’ suppliers and clients up and down the value chain.[51] In case of a bank, the emissions produced by oil and gas clients must count towards the bank’s scope 3 emissions, as they were facilitated through the banks’ investment. According to one estimate[52], the average bank’s Scope 3 emissions account for more than 95% of their total emissions.

The financial sector, both public and private, has a pivotal position in redirecting and redistributing flows of finance to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. The sector will only live up to this responsibility if better regulation is put in place, and scope 3 reporting rules on banks are made mandatory and apply without any exceptions. There are currently some proposals and budding regulation efforts to introduce this change. In the EU, these reporting rules are governed by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The latter has however been criticised for being ineffective in its benchmarking of standards for the financial sector.[53]

Prompt financial supervisors to request better data to assess climate risks

As suggested by our research, if banks do report misleading or ambiguous data on their real fossil fuel exposure, these numbers severely restrict the honest assessment of banks’ climate-related risks.

Like all corporates, banks are confronted with climate and transition risks in multiple ways, including when investing in carbon-intensive industries as they may face financial losses as these industries decline. The value of assets tied to these sectors could drop, leading to stranded assets, while banks may be held legally accountable for contributing to climate change or failing to adequately mitigate its impacts.