Rachel Etter-Phoya ■ Africa makes progress to end anonymous companies

Africa is making strides to unveil the real owners behind companies operating across the continent. The Tax Justice Network and Tax Justice Network Africa’s new study Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Africa in 2022 shows the progress on beneficial ownership transparency, why it matters and what more needs to be done.

‘Covidgate’ in Cameroon

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the International Monetary Fund lent and gave money to governments to help save as many lives as possible. Governments bought equipment, drugs and test kits. Knowing that public procurement can be a hotbed for collusion and corruption in all countries, the International Monetary Fund asked governments to make special governance commitments. In Africa, 34 governments committed to register and disclose the real people behind companies awarded contracts.

Nevertheless, money meant for saving people had a funny way of growing legs in many places during the pandemic. Commitments to transparency may not have been put into practice or done so in time or effectively, given the ‘Covidgates’ that sprung up across the world – from Brazil to Malawi.

Cameroon’s ‘Covidgate’ sheds light on the problem of anonymous company ownership. In 2020, the government set up a Special National Solidarity Fund to finance the health sector to protect Cameroonians from the coronavirus. But social media users soon started to leak information about embezzlement and fraud involving the solidarity fund. The press picked these up, and President Paul Biya called for an investigation.

With over 120,000 recorded Covid-19 cases, the Audit Bench of the Supreme Court of Cameroon revealed serious problems with the procurement process for equipment and drugs needed to help Covid-19 patients. Irregularities resulted in inflated prices for Covid-19 test kits and stocks of drugs disappearing.

In many cases, the information about the real owners of companies that won government contracts was “uncertain”. The Ministry of Health had set up a working group to oversee procurement. The president of this group was Ousmane Diaby, who also headed a division in the ministry. According to the Audit Bench’s audit, companies owned by Diaby won contracts.

It turned out that Diaby and his younger brother owned MG & Company, yet they managed to hide behind the manager. The company received nearly US $5 million, but there was very little work to show for it. This situation “is likely to be classified as a criminal offence”, according to the Audit Bench.

Spreading the spoils among family members didn’t stop there. The working group also awarded six contracts to three companies managed by Diaby’s older brother. Diaby did not notify the working group of the relationship. Here, the Audit Bench stressed that there is a “high risk of criminal liability associated with the award of these contracts”.

Despite the audit, there have been no sanctions or actions taken so far. Cameroon’s commitments on beneficial ownership transparency to the International Monetary Fund were a step in the right direction. Yet they appear not to have been put in practice in time or effectively, based on the Audit Bench’s findings.

Cameroon has taken further action on beneficial ownership transparency since then though. The new Finance Law of 2023 requires the beneficial owners of legal entities to register with the tax authority. This is an essential tool in addressing government procurement fraud which ultimately robs people of good healthcare.

Africa’s commitment to transparency

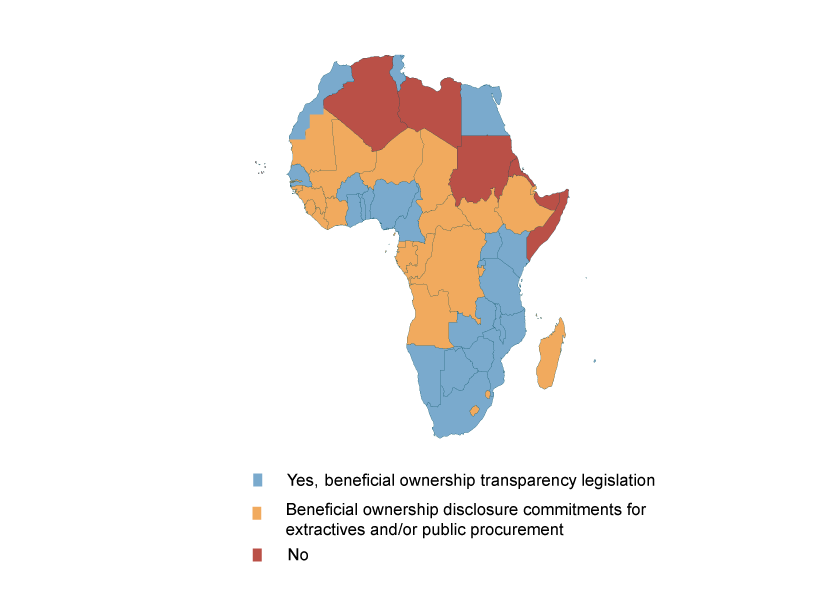

Cameroon is not alone in introducing laws for beneficial ownership transparency. At the start of 2023, 23 of 54 African nations required the human beings behind companies to register with a government authority.

More than half of the continent has specific commitments for sectors prone to risk: the extractive industries and public procurement. Governments in 28 African countries committed to disclose and make public the beneficial owners of companies in mining, oil and gas as part of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. This is important as people can hide behind opaque and complex company structures to win rights to extract Africa’s precious, finite resources. In many countries, commitments to beneficial ownership transparency first made in the extractive industries have also sparked the introduction of laws for all companies in every sector.

In the Tax Justice Network and Tax Justice Network Africa’s new study Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Africa in 2022, beneficial ownership transparency is analysed deeply in 18 African countries. Drawing on the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index 2022, we find that Botswana is leading the pack.

Botswana, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, and Tunisia require the beneficial owners of companies to register with a government authority and companies must notify authorities of any changes. What sets Botswana apart is that every single beneficial owner of a company must register. There is no threshold of ownership share below which a person becomes exempt. In contrast, Kenya, for example, has a threshold of 10 per cent. Hypothetically, this means that someone could set up a company with equal division of shares or voting rights between 11 people and not one of them would need to register, since individually the people would not meet the 10 per cent threshold.

The route to effective beneficial ownership transparency

In the extractive industries and public procurement in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, African citizens, journalists and law enforcement agencies have the best access to data. And, of course, the best data is not worth much if law enforcement agencies do not have the political space to act against wayward companies. Still, loopholes in beneficial ownership registration laws remain, which unscrupulous actors can exploit.

The Tax Justice Network has laid out its vision for effective beneficial ownership transparency in a Roadmap to Effective Beneficial Ownership Transparency. This is a blueprint for policy makers and citizens seeking to change legal frameworks. The roadmap sets out 10 targets that countries’ beneficial ownership frameworks should meet.

- Scope. All legal vehicles should be subject to beneficial ownership registration requirements. This means any entity that is not a living and breathing person should disclose the natural person who owns, controls or benefits from it.

- Definition of legal owners. All legal owners should register. This includes all who have a title or any direct interest in the legal vehicle.

- Definition of beneficial owners. All beneficial owners should register. This includes any natural person who in any way owns, controls, or benefits from a legal vehicle.

- Triggers for registration. All legal vehicles should be required to register beneficial ownership information if they seek to incorporate domestically, possess domestic assets, conduct domestic operations or have a domestic participant (eg a domestic legal owner, beneficial owner, settlor, director, etc).

- Identification information for all owners. Legal vehicles should be required to provide all identification details about both legal and beneficial owners to ensure there is no confusion of identity. This includes full name, place and date of birth, address, national ID number, tax ID number, and nature of ownership. This also allows for special checks (eg status as a politically exposed person). Legal vehicles should also be required to disclose the full ownership or control chain (all intermediate layers). This illustrates how each beneficial owner benefits or has ownership or control over the legal vehicle.

- Keeping information up to date. Legal and beneficial ownership registries should be updated annually, even if it’s just to confirm there were no changes, as well as updated when there is any change in the relevant information.

- Access to information. Legal and beneficial ownership data should be available to the public for free. Ownership registries should be available online in open data format.

- Verification of information. Beneficial ownership registries should automatically analyse data against other databases to check for consistency. For example, to confirm that all registered beneficial owners are alive. The online registry should introduce red flagging based on outliers and suspicious characteristics, such as a single person as a beneficial owner of thousands of companies.

- Sanctions for non-compliance. Criminal and monetary sanctions are important alongside administrative sanctions. Administrative sanctions include removing non-complying legal vehicles from the registry and revoking any rights from non-complying beneficial owners (eg votes or dividends).

- Special considerations. Countries should prohibit bearer shares, discretionary trusts and nominees. They should discourage complex ownership chains. Equally, countries should cover state-owned companies as well as listed companies and investment funds by applying even lower thresholds. In ideally, all countries should interconnect beneficial ownership registries with each other and with asset registries.

Related articles

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

When AI runs a company, who is the beneficial owner?

Insights from the United Kingdom’s People with Significant Control register

13 May 2025

Uncovering hidden power in the UK’s PSC Register

New article explores why the fight for beneficial ownership transparency isn’t over

Asset beneficial ownership – Enforcing wealth tax & other positive spillover effects

4 March 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024