Nick Shaxson ■ Tax Justice Network partnership with Federal Inland Revenue Service of Nigeria explores new audit tool

The Tax Justice Network is engaged in a pioneering joint research and data analysis project to support Nigeria’s Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) audit of Multinational Companies.

Like most countries, Nigeria has a plethora of international companies doing business there, and an under-resourced tax authority, so it only gets to audit a fraction of the international economic activity passing through. A tool to help prioritise audits could therefore be invaluable.

Under an agreement with the FIRS, signed in December 2019, the Tax Justice Network has developed a detailed risk assessment tool based on international data that can help Nigeria’s tax authority (and, hopefully, others in future) prioritise and target their audits of multinational companies. On January 11-13 we partnered with FIRS in a joint three day event, entitled “Workshop on effective audit of multinational corporations for domestic revenue mobilisation in Nigeria.” The workshop was attended by about 50 staff from different areas of the FIRS, including the International Tax Department in charge of transfer pricing audit, the Treaties Unit and the Exchange of Information Unit. Beyond the specific audit project, another aim of the workshop was to create and enhance synergies between these units.

Speaking at the workshop, FIRS‘ Executive Chairman Muhammad Nami said that “many rich Multinational Corporations do not pay the right taxes due from them, let alone pay their taxes voluntarily.” Nigeria is now paying greater attention to tax audits, he said, adding that “we have created more than 35 additional Tax Audit Units and deployed experienced and capable staff to take charge of these offices.”

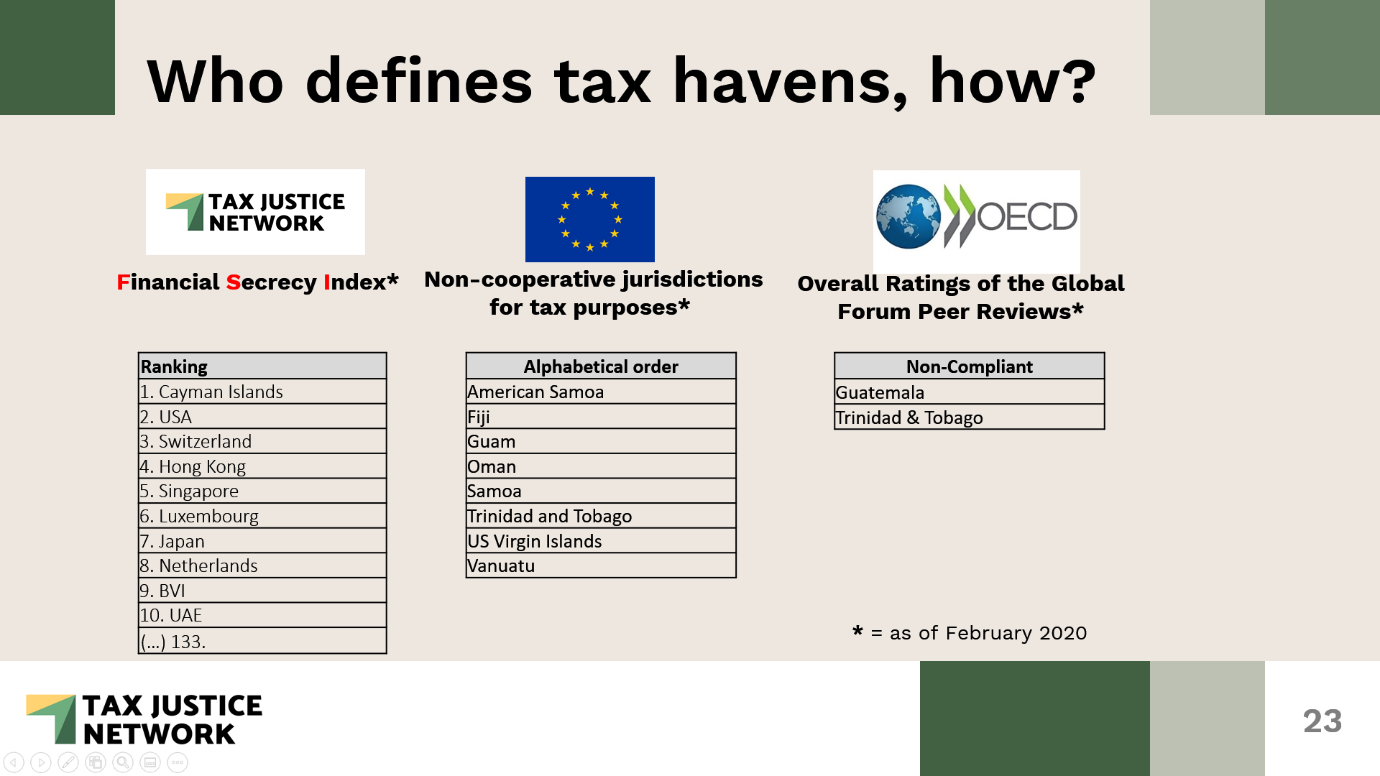

Tax havens, of course, constitute a major risk factor for the Nigerian tax authorities, and international data provided by official bodies in this area is hardly better than worthless. A slide we showed at the workshop illustrates this.

Nobody believes that American Samoa or Vanuatu, or Guatemala for that matter, are the top jurisdictions of concern for Nigeria, or for any other country. The world’s top tax havens are nearly all European or at least OECD countries, and these powerful groupings naturally exclude their own from blacklists. They are political. By contrast our rankings – the Financial Secrecy Index and the Corporate Tax Haven Index – are based on careful analysis of hard data, rather than on political considerations.

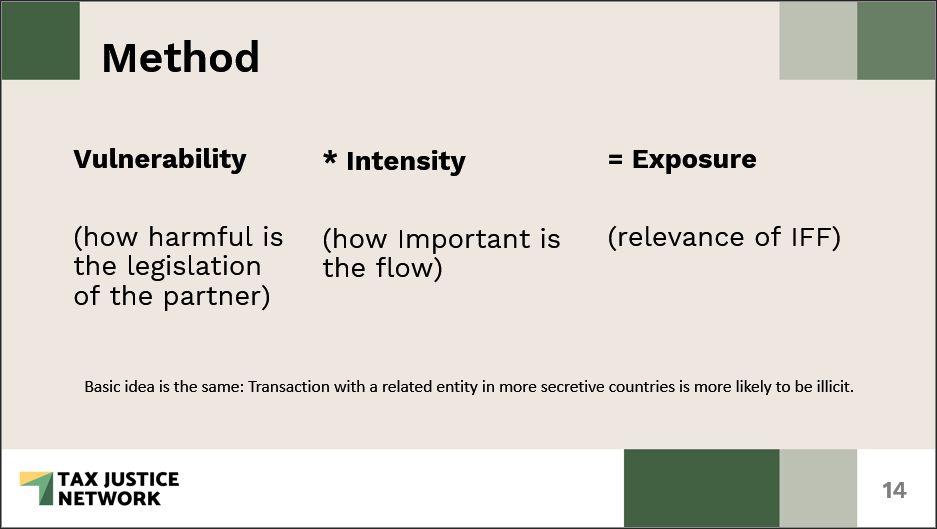

Essentially, both of our indexes involves combining two metrics for each jurisdiction: a “haven/secrecy score”, each based on 20 specific indicators, which tells us how risky the country’s legislation is in terms of enabling abuses; and a ‘scale weight’ telling us the size of financial flows through these jurisdictions. These scores are then mathematically combined to produce the final ranking.

However, our models have gone a step further, from the global, macro level analyses, to the bilateral macro level analyses: in our Illicit Financial Flows Tracker tool, we provide risk profiles of individual country’s economic cross-border activity based on their illicit financial flows risks in foreign direct investment, in their banking deposits abroad, etc. These risk profiles provide important pointers where to focus audit activity, and where to prioritise resourcing and how to target policies for information exchange better.

Yet, the next level is to take this analysis to the “micro” level. So instead of merely saying “Cayman‘s investment in my country provides risks”, the tax authority can scrutinize its taxpayers for related transactions and specific flows via Cayman, based on declarations and disclosure. Through our model, the tax authority can systematically calculate the risks for illicit activity of individual taxpayers based on each taxpayer’s entire cross-border transactions with all secrecy jurisdictions (not only with Cayman) to flag and rank those taxpayers incurring most geographic risks. The result is a ranking of taxpayers causing most of a country’s vulnerability in their cross-border economic transactions – and thus allowing the country prioritise its audits.

The analysis rests significantly on a core formula: Exposure = Vulnerability x Intensity. This slide illustrates the top-level view of this.

Data will be mined from certain components of transfer pricing documentation submitted as part of annual tax returns, with appropriate confidentiality and anonymisation safeguards in place. The key risk dimension driving the model is geographical risk, looking at where the connected companies and individuals (eg shareholders, intra-group trade with related companies, directors) are incorporated and/or tax resident; and at the related volume of costs or income from high secrecy jurisdictions.

In this way, tax authorities will be able to examine the risks of different corporate structures in a speedy manner and to process large volumes of corporate tax data fast, teasing out those corporate groups whose finances are most exposed to geographic risks. The model thus allows them to understand the flows better, and prioritise their audits accordingly. Similar kinds of exercises can be carried out looking at wealthy individuals, instead of corporate structures, using the data categories from our Financial Secrecy Index.

This model now needs to be subjected to the hard knocks of the real world, and refined accordingly. We will be delighted to receive feedback and are expecting that once road-tested in Nigeria, it can be useful to a range of other countries in Africa and beyond.

We’re proud to partner with Nigeria in countering illicit financial flows by sharing knowledge, capacity building and pioneering new methods and tools.

Related articles

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

The bitter taste of tax dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss swindle’

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025