Andres Knobel ■ Beneficial ownership definitions: determining “control” unrelated to ownership

Most beneficial ownership definitions are based on ownership thresholds or voting rights. But there are ways to control a company without holding any shares. This brief explores some of these gaps and proposes ways for authorities to address them. This brief is also available to download as a PDF.

The ownership bias

The Glossary of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations related to anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) defines a “beneficial owner” as the natural persons who ultimately own, control or benefit from a legal vehicle such as a company, partnership, trust, foundation, etc, or who have effective control over them. It is clear that the definition refers both to “ownership” or “control”, however, in the past few years since the Financial Action Task Force published its recommendations, a warped implementation of this definition has taken hold of beneficial ownership registers in many countries. That implementation warps “ownership” or “control” into “controlling ownership”.

While most countries’ laws use the Financial Action Task Force’s Glossary definition, the process of identifying a beneficial owner in practice can differ. Based on the Financial Action Task Force’s Recommendation 10 (which refers to how financial institutions should undertake customer due diligence), mechanical tests are often incorporated in regulations, such as the need to identify any individual who directly or indirectly owns shareholdings above a certain threshold as a “beneficial owner”. One widely used threshold to determine who a beneficial owner is, is the “more than 25 per cent” of ownership or voting rights, which we’ve criticised in previous research and blogs.

However, returning to the original definition, beneficial ownership is not about having a level of ownership that is substantive or large enough to be considered a controlling ownership, but merely about having ownership in the first place or control or benefit. We thus understand that there should be no threshold and anyone holding at least one share should be identified as a beneficial owner. As the paper on the updated state of play of beneficial ownership registration reveals, based on the findings of the Financial Secrecy Index published in 2020, four jurisdictions are already requiring beneficial ownership registration whenever anyone holds at least one share: Argentina, Botswana, Ecuador and Saudi Arabia.

One argument in defense of the “more than 25 per cent” threshold is that only ownership that meets this threshold classifies as “controlling ownership” and so is worth registering. But simply implementing the threshold itself shows how the logic of arbitrarily distinguishing and registering “controlling ownership” falls apart in practice. If Paul owns 30 per cent of a company and Mary owns the remaining 70 per cent, both of them would have to register as beneficial owners (because both pass the 25 per cent threshold) despite Paul having no control at all. Mary has the majority of the votes and so all of the control. In the case of trusts all parties have to be identified as beneficial owners, including the settlor and the beneficiaries, even though neither may have any control over the trust and the trustee (at least on paper, since trusts can easily be abused).

While “control” may be relevant to finding the responsible individuals who controlled a legal vehicle (eg company) involved in a financial crime, ownership (regardless of the threshold) is relevant for other purposes. A 0.01 per cent of a listed company may be worth millions of dollars despite giving no control over it. Knowing the beneficial owner of that 0.01 per cent may be important for asset recovery, but also to determine if the person could explain how they purchased those assets in the first place or whether they have paid corresponding wealth tax, if applicable. Unfortunately, listed companies and investment funds enjoy a high degree of secrecy, either because they are exempted from beneficial ownership registration laws or because the high thresholds mean that hardly any individual will pass the 25 per cent threshold. Therefore, only the manager or CEO will be identified. While these entities may have to disclose some information to the securities regulator, usually at 5 per cent thresholds, that is still not enough. An example of this relates to a study that was unable to find the beneficial owners of Berlin real estate through investment funds.

In any case, the disclosure of the beneficial owners holding directly or indirectly at least one share is a very important step, but it is not enough. The legal owners and the full ownership chain should also be disclosed to detect other abuses, eg circular ownership. Moreover, the key point is not to stop the analysis once a person having ownership above a certain threshold was identified (either one share or more than 25 per cent), but to go further until every individual with control through other means is also disclosed.

How to find those individuals with control through other means (different from ownership)?

The UK and then the 5th EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD 5) include in their beneficial ownership definitions those individuals with more than 25 per cent of the voting rights or the right to appoint or remove the majority of the board of directors. “Influence” or “effective control” is also mentioned. In principle, it is good to leave the door open with these general provisions such as “anyone else with effective control over the legal vehicle”. This allows the staff at a registrar or bank in charge of assessing a legal vehicle’s beneficial ownership structure to dig further and to try to understand the control structure. However, for those without the will, time or experience, it would be good to have some more “mechanical” approaches.

For instance, there are low-hanging fruits as we proposed in our checklist for beneficial ownership registries. Those with power of attorney or any similar right to administer the legal vehicle or its bank accounts (transfer or withdraw funds) should also be registered. Given that since 2020 the EU requires financial institutions to report discrepancies between the information declared by their customers and the information available in beneficial ownership registries, reported discrepancies should detail whether those managing the bank accounts are also mentioned in the beneficial ownership register.

However, it is not enough to register those with a power of attorney or those who manage bank accounts. There are more complex cases of control or influence through means different from ownership. These cases create loopholes which individuals case use to avoid beneficial ownership registration. We will discuss these cases here so that government can take action to safeguard against them.

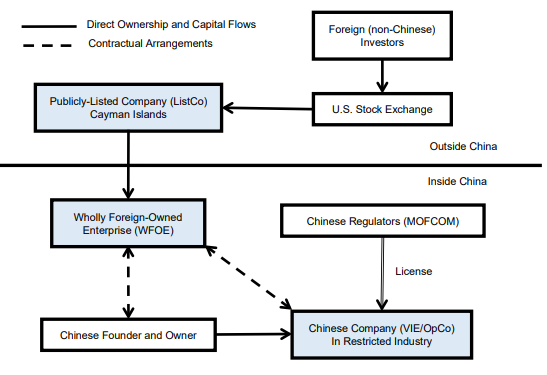

a) Combination of commercial contracts. The case of the VIE structure for foreigners to “own” Chinese strategic assets meant for Chinese owners

The Chinese Variable Interest Entity (VIE) achieves the same effect of ownership and control, not through holding shares or votes, but through different commercial contracts.

As Whitehill and Coppola describe, China has restrictions on foreigners owning or investing in strategic industries (eg internet platforms, financial services, telecommunications, energy, agriculture). To avoid these restrictions the VIE structure works as follows:

Source: Brandon Whitehill, “Buyer Beware: Chinese Companies and the VIE structure”

The Variable Interest Entity (VIE) is the legal vehicle engaged in the strategic industry which can only be held by Chinese owners. Another company, the Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprise (WFOE) is created in China. As its name indicates, it can be owned by foreigners because it is not related to a strategic industry. Foreigners may invest in the WFOE through a listed company, which may be in Cayman or anywhere.

What we care about are the dashed arrows between the WFOE (foreigners) and the VIE (strategic industry). They show how it is possible to have control and all the economic benefits of ownership, without actually owning the VIE.

Whitehill describes the necessary contracts and agreements involved:

- A loan agreement and equity pledge agreement: WFOE (foreigners) transfers money to the VIE (strategic industry) as an interest-free loan and gets as collateral all of VIE’s assets and liabilities.

- A call option agreement: WFOE (foreigners) has the right to purchase the VIE at a pre-determined price, usually the amount of the loan agreement.

- A power of attorney in favour of WFOE (foreigners), granting it shareholder rights such as voting, attending shareholder meetings and submitting shareholder proposals.

- A technical services agreement and an asset licensing agreement designating WFOE (foreigners) as the exclusive provider of services. These “services” justify why WFOE may get all of the VIE’s pretax income (as payment for those services).

In essence, a few contracts may replace ownership by giving control (through a power of attorney) and rights to all income and assets (through service agreements).

b) The use of derivatives and other financial instruments

If the Chinese VIE structure sounded complex, at least it was possible to understand it. In 2006 Henry T. C. Hu and Bernard Black published “The new vote buying: empty voting and hidden (morphable) ownership” describing that “hedge funds have been especially creative in decoupling voting rights from economic ownership. Sometimes they hold more votes than economic ownership – a pattern we call empty voting. In an extreme situation, a vote holder can have a negative economic interest and, thus, an incentive to vote in ways that reduce the company’s share price. Sometimes investors hold more economic ownership than votes, though often with morphable voting rights – the de facto ability to acquire the votes if needed. We call this situation hidden (morphable) ownership because the economic ownership and (de facto) voting ownership are often not disclosed.”

Some of these “simple” strategies involve lending shares for the day in which there is a vote and then returning them. This strategy is very similar to the Cum-Cum tax fraud, where shares were borrowed not to vote, but to defraud tax authorities. In the tax fraud, the holder of shares lends them before dividends are distributed to a party entitled to dividend tax reimbursement, eg based on their residence. After dividends are distributed, the tax paid and reimbursed, the shares can be returned to the original owner (who shouldn’t have benefitted from the reimbursement). Both parties agree to share the “windfall profit” from the evaded tax.

Instead of a loan, shares could also be sold with a right to buy them back either by contract, or by buying a “call” option from someone else, which is a financial instrument giving you the right to purchase a specific share at a given price.

Other strategies are much more complex and unless you have a very strong knowledge of finance, you’ll need to read the 99-page paper by Hu and Black and look up all the finance jargon (of which there’s a lot!) to be able to fully understand the strategies. As even the authors acknowledge, “the variety of decoupling strategies can be overwhelming”. They list some of them. For example, “empty-voting” strategies (more votes than economic ownership) include “share ownership hedged with equity swap” or “share ownership hedged with options”. Basically, voting rights are kept because shares are kept, but economic benefits are transferred by giving someone else a right to the share value. Another strategy, “insider hedging” refers to founders or CEOs who reduce their economic exposure without selling their shares (so as not to alert anyone). They keep their shares and votes, but they reduce their economic exposure by limiting losses and reducing potential gains. They do this by engaging in “zero-cost collar” which involves buying a put option (right to sell at a specific price) while simultaneously selling a call option (allowing the counterparty, the buyer, to purchase the share at a specific price). These strategies may also be reversed, where a player doesn’t have any votes (or shares), but is still exposed to the shares’ performance through financial instruments. This would have the same economic effect as holding those shares directly themselves. The authors described that based on market conditions, hedge funds engaging in these strategies may have a de facto voting right at their discretion (by unwinding the financial contract). They gave an example of hedge fund P: “[P] held ‘morphable’ voting rights – which could disappear when [P] wanted to hide its stake, only to reappear when [P] wanted to vote.” (page 837)

All of these hedge fund strategies may have more to do with securities law (and hopefully are understood by securities regulators to prevent abuses and more financial crises). For our purposes, financial instruments such as derivatives used and abused in the financial industry show that it is possible to own shares but give economic rights to someone else, or vice versa: having exposure to a share’s performance as if you owned it, without holding it. The same applies to voting rights.

c) Trusts

Trusts are very tricky instruments. In theory, a trust involves a settlor transferring assets to a trustee, who has to manage the trust assets and income in favour of the beneficiaries according to the settlor’s indications in the trust deed. This structure suggests at least three different people (and in many cases it may be so). However, in practice, a trust may involve only two people (if the settlor is also “a” or “the” beneficiary), and even only one person (if the settlor also controls or “is” the trustee). Depending on a country’s laws, there may be restrictions to the settlor being also the trustee or the beneficiary, but this may be “fixed” with secrecy: the settlor may be appointed as a beneficiary at a later time or the settlor may receive distributions from the trust simulated as “third-party transactions”, eg a loan that will never be repaid, or a sale or purchase of trust assets at a bogus price. The settlor could also “be” the trustee, by appointing a company as a trustee and the settlor owning or directing the corporate trustee. The appointment of a protector or enforcer to control the trustee is another way to control it.

The definition of trusts’ beneficial owners usually involves identifying all parties: settlor(s), trustee(s), protector(s), beneficiaries and classes of beneficiaries, and any other individual with effective control over the trust.

Trinidad and Tobago’s Guidelines issued by the Central Bank have a good description of what this effective control may mean in practice. In addition to requiring the identification of “the person providing the funds if not the ultimate settlor”, they add “the name of the individual who has the power (whether exercisable alone, jointly with another person or with the consent of another person) to: dispose of, advance, lend, invest, pay or apply trust property; vary the trust; add or remove a person as a beneficiary or to or from a class of beneficiaries; appoint or remove trustees; and direct, withhold consent to or veto the exercise of a power such as is mentioned [above].”

However, it may be difficult getting this person with effective control to be disclosed, especially if they do not have a proper role such as a protector. For instance, the settlor could set up a discretionary trust and write a secret “letter of wishes” directing or instructing the trustee, without needing to appoint a protector. This would make the arrangement riskier from the perspective of the settlor, but in exchange the settlor would be able to separate itself from any idea of control over the trust. This is especially problematic if courts understand that the fact that the trustee does exactly what the settlor indicates, doesn’t mean “control” by the settlor but a mere startling coincidence between the settlor’s and the trustee’s desires. A law firm described Jersey’s court decision in the Esteem case:

It is important to note that the Court found that Sheikh Fahad did not retain dominion and control, even though numerous transactions were made at Sheikh Fahad’s request and no such request was ever refused. In this regard, the Court stated, “In our judgment trustees who consider a discretion in good faith… cannot be said to be under the substantial or effective control of the requesting settlor… it cannot be sufficient simply to show that, in practice, trustees have gone along with a settlor’s wishes [because this result could be] consistent with the trustees having exercised their fiduciary responsibilities properly [by] having decided that each request of the settlor was reasonable and in the interests of one or more beneficiaries.”

d) Family influence

If determining control by a settlor is difficult, determining influence by a family member, especially by one who has no shareholdings or votes, may be impossible. Attendance at board meetings, or some communications may be revealing, but they could easily be camouflaged. On the bright side, if a person is employing family members or close associates to influence them, it will be easier to determine who the person is by looking at the family circle.

Discussion

Freedom of choice when designing contracts and financial instruments coupled with virtual encrypted communications between parties may create unlimited ways to control or influence a person (or a legal vehicle) without leaving any trace.

An experienced officer at a bank, commercial register or corporate service provider may be able to detect that there is something odd with a legal vehicle and inquire further. Unexperienced or unwilling officers wouldn’t bother unless required to do so by the law.

A first proposal would be to require more disclosures: any relevant power of attorney to manage a legal vehicle or its assets would a very good first start. Disclosure of contracts affecting shareholdings, votes or income would reveal the Chinese VIE structure and some derivative financial instruments.

One possible way to encourage registration of these related contracts would be through giving “constitutive effect” to the beneficial ownership register. Unless a contract has been registered, it shouldn’t be enforced. In other words, a Chinese VIE company would be unable to transfer all of its income to its unique supplier (the WFOE company held by foreigners) unless the contract has been registered, and the parties clearly identified. By the same token, banks, brokers and financial intermediaries should be prevented from transferring money, votes or shareholdings among financial players, unless these contracts have been properly registered in the beneficial ownership register (in relation to each company that the shares or votes belong to).

This disclosure may seem excessive and useless by those claiming that all these people may have no control or relevance in an investigation about a company. But excessiveness is often relative. Capitalists said labour laws, paid holidays and a five day working week were excessive. A few years ago, asking banks to collect information on all non-residents for automatic exchange of information was considered excessive. All these practices are unquestionable realities.

As for uselessness, the argument misses the point. Of course, not every person identified as a beneficial owner or party to a contract related to the shareholdings, income or votes of a legal vehicle will be considered relevant, let alone responsible for any wrongdoing. The idea however is for authorities to have all the information in the first place about all the people who may relevant – exactly the way every airport passenger has to go through security despite the fact that nearly all of them aren’t terrorists. Having information on all persons that may be related or influencing a legal vehicle would also help detect unknown cases. For example, this comprehensive disclosure of information may reveal an individual that has no shareholdings but that is nevertheless related to a very high number of legal vehicles. It would also enable looking at the “shared” people between two apparently unrelated legal vehicles (for example, an investigation into sophisticated money laundering may relate two companies only because they were involved in identical financial transactions, despite not having anything in common).

To put it simply, criminals and those abusing financial markets have way more resources, cooperation and creativity than authorities. At the very least, authorities should require information that may be end up being relevant for investigations.

On the other hand, it’s one thing to require all this information to be disclosed, it’s another to understand what the disclosed contract says. This touches a more radical proposal which questions whether societies need this much freedom of choice in the first place when it comes to setting up complex legal vehicles, with complex control structures and adding complex contracts that make the whole arrangement even harder to understand for outsiders.

It is very likely that proponents of the supposedly infallible self-regulation of the free market would oppose any extra regulation that limited finance transactions. Similar disapproval may come from country authorities misguidedly attempting to attract investment. However, it may be time for countries and policymakers to start questioning whether the complete freedom of establishing unlimited structures serves society as a whole. Or rather, whether we should start limiting the types of legal vehicles, length and complexity of ownership chains, and financial instruments or contracts that distort what the registered ownership information seems to suggest.

Even if someone were to agree with these ideas, at least in theory, they may be worried not only about the loss of investment but also costs and extra burdens on current economic players, especially small and medium enterprises.

The extra benefit of these ideas is that they wouldn’t affect most small and medium players. For instance, in the UK, close to 80 per cent of companies have very simple structures: either a natural person holding the company, or one other company in between. For these 80 per cent, all these extra disclosure requirements and limits on complexity would be irrelevant. Assuming they are already using very simple structures without any hidden contract or financial instrument, they would not need to do anything differently.

The remaining 20 per cent, however, should need to explain to policymakers how the complex structures with contracts that may give control or economic exposure to others benefit society as a whole. Alternatively, instead of banning any unjustified contract affecting votes or economic benefits over a legal vehicle, countries could establish limits on the number of contracts by requiring one party to the financial transaction to own or hold the underlying shares. This would at least prevent other players from speculating on assets that none of them hold or own.

To sum up, the measures that would affect financial players the least would involve requiring more information about any contract that affected control or economic benefits over a legal vehicle. However, effectiveness of such measures may be limited even if all players disclose all contracts, because authorities would need to understand the contracts in the first place. This leads to a question about whether it makes sense for authorities to always be running (or walking) behind criminal and abusive practices, or whether it is time to change the rules of the game and authorise only what authorities confirm makes sense and benefits society as a whole. To determine this, policymakers could use a simple criterion (that would also be relevant to differentiate between tax abuses and legitimate tax minimisation): if it is meant to be authorised by the law, it should be very simple and easy to implement (and understand). If the only way in which a scheme works is by employing many different legal vehicles, transactions and contracts which make no sense to any outsider, it is probably not meant to be allowed, and thus should not be allowed. This may mean less legal vehicles and less financing opportunities, but are we sure that this is a bad thing?

Summary of the proposals to start the discussion

- More information. Require for each legal vehicle more information on any power of attorney, contracts, agreements or arrangements (especially about financial instruments) that affect either control (eg voting capabilities or management) or economic benefits (either through ownership or exposure, eg derivatives, or through a right to all of a company’s income). This information should be part of the record of each legal vehicle. While the contract may not be public, the basic elements should be.

For example, the beneficial ownership register would disclose about company A: legal owners, ownership chain, beneficial owners, directors, people with power of attorney and any contract/transaction/agreement that affects control or ownership (eg, exclusive supplier agreement, equity-swap agreement between shareholder A and hedge fund B giving hedge fund economic exposure as if it owned shareholder A’s shares).

- Establish limits on the complexity of legal vehicle’s ownership and control structure. Policymakers should start exploring and discussing establishing limits on the types of legal vehicles (eg ban discretionary trusts), length of ownership chains (eg allow only two layers between a legal vehicle and its beneficial owners), quality of ownership chains (eg allow only legal vehicles that had to disclose their legal and beneficial owners in their country of incorporation) and the contracts, agreements or arrangements that may affect control or exposure to the economic benefits of a legal vehicle (eg allow such contract if one party holds the underlying shares or interests in a legal vehicle).

Freedom of choice would only exist within the set limits. If a legal vehicle intended to go beyond those limits, eg set up five layers between the legal vehicle and its beneficial owners, they should justify the commercial need for it (which should not be related to secrecy or tax minimisation). If authorities understood and agreed on the benefits of the more complex structure, it should not only be allowed, but it should be incorporated into existing regulation to allow everyone else to use the same structure, which would become within the set limits. In essence, authorities would only authorise what they may handle and understand, similar to a compliance officer in a bank allowing or rejecting risky clients.

Related articles

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

When AI runs a company, who is the beneficial owner?

Insights from the United Kingdom’s People with Significant Control register

13 May 2025

Uncovering hidden power in the UK’s PSC Register

New article explores why the fight for beneficial ownership transparency isn’t over

Asset beneficial ownership – Enforcing wealth tax & other positive spillover effects

4 March 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024