Tax Justice Network ■ Why many Berlin real estate owners remain secret despite new transparency laws

Cayman Islands, a place of registration for several Berlin companies indirectly owning German real estate. Photo: Michael Klein

Guest blog by Christoph Trautvetter, Netzwerk Steuergerechtigkeit

For anyone who cares about beneficial ownership transparency the spotlight should be on the EU – where public beneficial ownership registers became mandatory in 2020 – and Germany, which is struggling with the issue of anonymous real estate ownership in the face of a looming review by the Financial Action Task Force and a public alarmed by rising prices, which have exploded, in part due to an influx of anonymous international investment.

Just in time for the EU directive – but later than the UK, Denmark or Luxembourg – Germany made its beneficial ownership register public at the beginning of 2020 and has become one of the first countries worldwide to oblige foreign real estate buyers to register in the local beneficial ownership register.

A new study by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation traces the ownership of more than 400 companies owning real estate in Berlin through public and commercial registers worldwide – including the German and other European beneficial ownership registers – concluding that nearly a third remain anonymous and transparency remains an illusion. It takes 15 examples and shows how implementation and enforcement of beneficial ownership transparency has failed in Germany (and other European registers) and why the EU definition of beneficial ownership remains fundamentally flawed.

When the German parliament debated the implementation of the EU’s 5th anti money-laundering directive most politicians, experts and the public agreed it should go ahead. The national risk analysis and the financial intelligence unit had identified real estate as a major risk area for money laundering and the Finance Ministry’s Secretary of State asked parliamentarians for additional ideas, in particular in the area of real estate. A prosecutor from Berlin pointedly reminded the parliamentarians that anyone who buys a house in Berlin using a company from any secrecy jurisdiction stays beyond the reach of law because prosecutors have no way of determining the real owners. And last but not least, due to soaring purchase prices and rents, many tenants are no longer willing to accept anonymous investors and dirty money. The press took notice. Everyone wants to know: Who owns our cities?

Besides opening the beneficial ownership register to the public (as foreseen in the EU directive), parliament passed one amendment that obliges any company from outside the EU wanting to buy real estate in Germany to register, and another allowing – or obliging – notaries and real estate agents to increase scrutiny of real estate transactions.

But despite all these efforts the study by the Rosa Luxembourg Foundation shows that answering the question of who owns Berlin remains impossible for two reasons:[1]

- The German beneficial ownership register was badly designed and is not effectively enforced.

- The concept and definition of beneficial ownership in the EU and FATF guidelines is seriously flawed.

| Anonymous companies owning Berlin real estate | 135 of 433 |

| Missing entry in the transparency register despite compulsory registration | 83 of 111 |

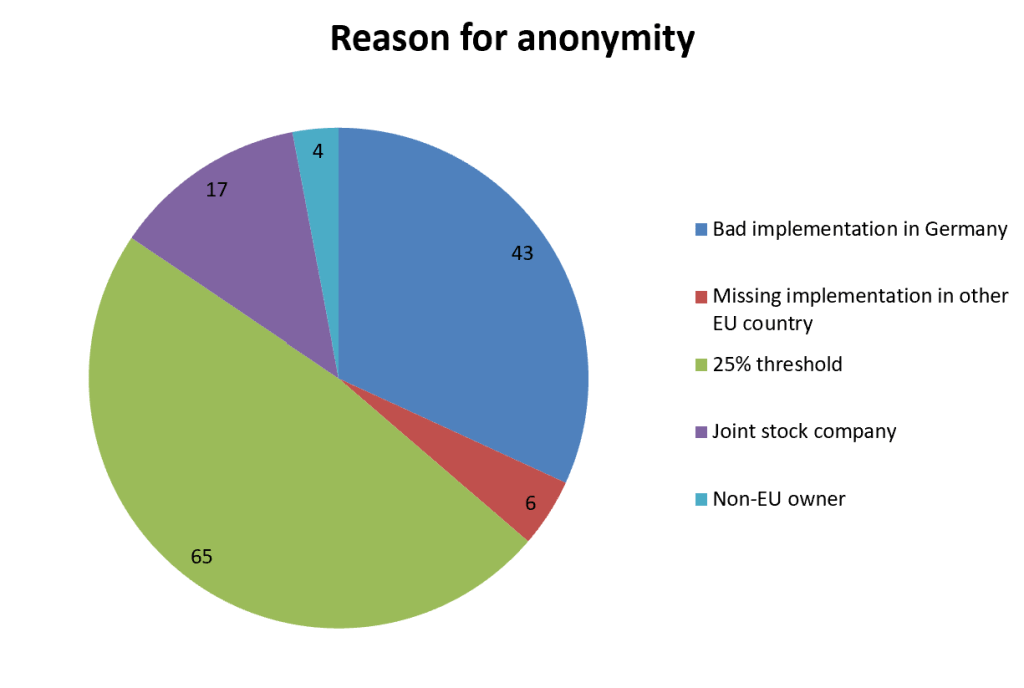

| No beneficial owner according to current definition (25%) | 82 of 135 |

Under these circumstances the new rule forcing foreign companies to register in the beneficial ownership register is purely symbolic and easily circumvented. Out of 433 companies owning real estate in Berlin that were analyzed for the study 135 remained anonymous. Of 111 relevant cases – i.e. where the beneficial owner was not already known through the German company registers – there was no entry in 83 cases and a real beneficial owner in only 7. In at least 82 out of the 135 cases the real owners remained anonymous, using joint stock companies and investment funds to ensure they didn’t surpass the 25% threshold to register as a beneficial owner.

Germany vs. EU – the state of play of beneficial ownership registers

Even though beneficial ownership registries have been obligatory in the EU since 2017 and their publication was due at the beginning of 2020, only six countries (UK, Denmark, Luxembourg, Latvia, Slovenia, Bulgaria) made their register freely accessible by then. Seventeen countries either don’t even have a beneficial ownership register (such as the Netherlands and Cyprus) or haven’t made it public (such as France and Spain).[2] Germany created the register in 2017 and made it public by 2020 but there are two big issues that hamper its usefulness:

First, Germany is one of only four countries (with Malta, Sweden, Norway) that don’t make the register mandatory. On top of that, instead of integrating the beneficial ownership register with existing ones (like Denmark, the UK or Malta) Germany (like Austria or Luxembourg) opted to create a separate register that is badly integrated. In theory, companies that already register their beneficial owners in Germany are spared additional bureaucracy. In practice this doesn’t work. As limited companies already have to publish all shareholders in the company register, typical real estate owners – Germans owning real estate through German companies – are fully transparent. But there are also many foreign companies that hold shares of German real estate companies and whose beneficial owners consequently can’t be found in the German registers. Nearly all of these German companies failed to register in the German beneficial ownership register and, because of the poor integration of the two registers, the oversight body is unable to efficiently identify companies with foreign shareholders that should register in the beneficial ownership register.

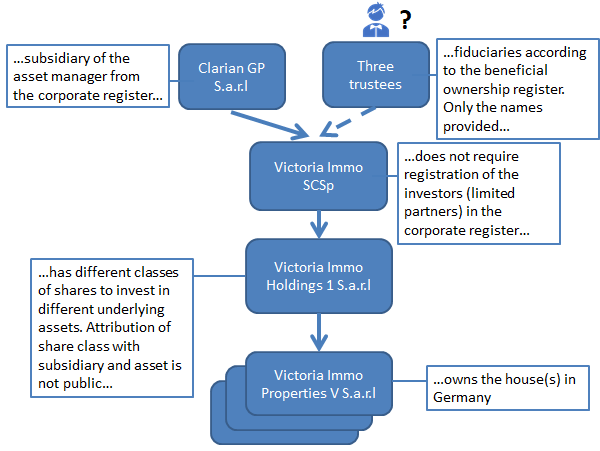

Second, a significant share of Berlin real estate is owned by joint stock companies, investment funds or companies claiming to have no beneficial owner above the 25% threshold set by the EU definition. As German joint stock companies, they have to disclose anyone owning more than 3% of their shares and record ownership in the internal, non-public shareholder register – but they often record and know only the name of the wealth manager or the bank administering their shares, rather than the beneficial owner. Many of the investment funds are structured as a combination of Cayman Island partnerships and Luxembourg SCSp – which means they don’t register their investors in any of the existing registers. Likewise the Seychelles LLC owning German real estate via Luxembourg can easily claim to have no beneficial owners under the existing criteria without much chance for verification – especially considering the absence of proper registration, the missing international cooperation and the existence of vehicles such as protected cell companies in many of these secrecy jurisdictions.

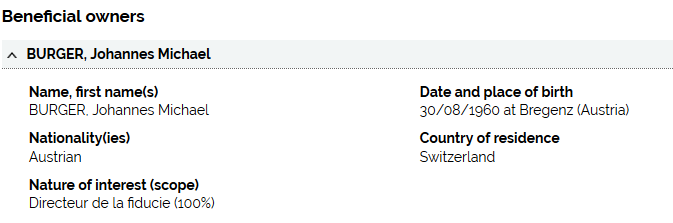

The cases analyzed in the study show the potentials and limits of beneficial ownership registers in various ways. One particularly instructive case revolves around a traditional book shop in Oranienstraße (Kreuzberg) fighting against eviction by an anonymous owner that might well turn out to be the heirs of the Tetra Pak fortune – mostly philanthropists with a reputation to lose.[3] While the owners use an SCSp to avoid registering the shareholders in the normal corporate register, the beneficial ownership register contains the names of three lawyers working for Liechtenstein’s biggest multi-family office.

But the beneficial ownership register doesn’t contain the name of the trust or vehicle they are representing nor of the final beneficiaries (which would remain unknown anyway because Liechtenstein hasn’t adopted a beneficial ownership register yet).

Extract from the Luxembourg beneficial ownership register

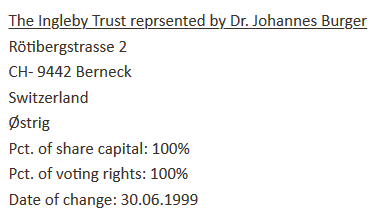

In contrast the Danish beneficial ownership register (concerning an unrelated company) lists the same three lawyers as representatives of the Ingleby trust connected to the Tetra Pak heirs. Because of this ambiguity the owners of the bookshop in Kreuzberg continue to wait for the confirmation of who is trying to evict them and whom to appeal to.

Extract from the Danish beneficial ownership register

The examples and results of the study show – creating a new and parallel register and trying to avoid double-entries by exemptions for beneficial owners already registered in traditional registers was a very bad idea. To fulfill the FATF requirement of effective beneficial ownership transparency Germany will have to ensure proper integration and consistency of the registers or learn from its neighbors and change the approach. The German case is also a perfect case example to demonstrate that without public scrutiny completely dysfunctional registers can proliferate for years – something that is hopefully going to change now that the register is public. And finally the study shows that through the EU and worldwide a lot of work remains to make existing beneficial ownership register work and to eliminate the limitation that allow the proliferation of anonymous ownership.

[1] In addition, German land registers are accessible only after proof of a legitimate interest. That’s why – instead of doing a full analysis or a random sample – the study was based on owners identified through a crowd-based collection of ownership data from tenants, journalists and local politicians.

[2] For a good overview see https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/corruption-and-money-laundering/anonymous-company-owners/5amld-patchy-progress/ . More detailed country profiles can be found at: https://www.pwc.nl/nl/assets/documents/the-ubo-register-update-december-2019.pdf

[3] https://www.neues-deutschland.de/artikel/1135512.verdraengung-kartonmilliarden-gegen-buecher.html (in German)

N.B. The Tax Justice Network apologises for the use of an image of a palm tree in this article to represent tax havenry. The palm tree trope is widely used across media to associate international tax abuse largely or exclusively with small tropical islands whose populations are predominantly non-white and/or Black-majority. Evidence shows that the vast majority of international tax abuse is driven by rich OECD countries like the UK, US, Switzerland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands – yet it is small island nations that are often targeted by international policymakers while rich OECD countries are afforded exemptions. This colonial and structurally racist situation is bolstered by the use of the palm tree/island trope in media coverage of tax abuse. While the Tax Justice Network took the internal decision years ago to ban the use of the palm tree trope in our publications, we have kept our past uses of the trope up in order to be transparent about our past actions, rather than erase them, and to reaffirm our commitment to reject the trope going forward.

Related articles

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

When AI runs a company, who is the beneficial owner?

Insights from the United Kingdom’s People with Significant Control register

13 May 2025

Uncovering hidden power in the UK’s PSC Register

New article explores why the fight for beneficial ownership transparency isn’t over

Asset beneficial ownership – Enforcing wealth tax & other positive spillover effects

4 March 2025

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

Many legal scholars consider the Berlin rent price cap unconstitutional at least, in parts for infringing the constitutional property guarantee, the freedom of contract, and for procedural reasons.

Nice one. Quite informative