Nick Shaxson ■ Big bills: let’s recall them all

In June 2014 we wrote an article about Big Bills: those high-value cash notes that are primarily of use to the world’s criminals (when was the last time you saw a 500 Euro note in the flesh, for instance?) The countries that print them can literally make a killing from so doing.

Big bills have been in the news again recently, with proposals in Europe stop printing the damn things. A New York Times headline today summarises: Getting Rid of Big Currency Notes Could Help Fight Crime.

Now James Henry, a TJN Senior Adviser, has an article in The American Interest looking at the issue of big bills:

“Harvard professor and former [U.S.] Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has finally acknowledged the dodgy role that “big bills” ($100 bills, €500 notes and CHF 1,000 notes) play in global money laundering, corruption, tax dodging and organize crime, and has called for a “big bills” currency reform.

Well, welcome to the club. Indeed, I first proposed a $100 bills reform idea way back in the 1970s, when Summers and I were still in grad school. More recently, with TJN’s support, I was also among the first to campaign for a similar reform by the ECB with respect to €500 notes.”

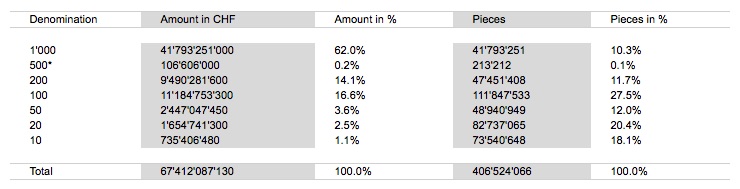

Which are the countries with the biggest of big bills? Well, there’s Switzerland, with its 1,000-Franc (CHF) note. Switzerland is ranked at the top of our Financial Secrecy Index of the world’s top tax havens. And look at the outrageous deliberateness of it all:

Then there’s Singapore, with its ten thousand dollar note. Singapore is ranked fourth in our Index. Singapore has stopped issuing the things, but that’s hardly a comfort: a third of its outstanding notes are either the 10,000 or 1,000 dollar note: worth around US $7000 (or $700) apiece. (See p326 here for the data.)

And there is also the good old hundred dollar bill from the United States: not nearly so hefty, but still a storage mechanism of choice for the world’s crooks: three quarters of the $1.3 trillion in cash outstanding (p426) are the big ones. Henry:

“Back in the 1970s there were less than four $100 bills in circulation per U.S. resident. Now there are more than thirty, at least 75 percent of which are working around the clock offshore to facilitate everything from drug traffic and bribery to sweatshop labor and terrorism.”

The U.S. is ranked at number three in our index. But we should add that we’re ambivalent about this one: plenty of ordinary folk find them useful, and they’re much lower value than the other vehicles.

One might be starting to discern a pattern here. But wait – there’s also the European 500 Euro note, pictured at the top: the source of all the current kerfuffle. That messes up the pattern: Europe isn’t exactly tax haven central, is it?

Well, yes it is. Germany is actually ranked eighth in our index, for instance — and for good reason. But perhaps more importantly, look at this story from Euractiv.

“Since the creation of the euro, the number of €500 notes has multiplied by six, while the number of €10 and €20 notes, highly called-for in day-to-day business, has remained stable.

Of the €1,000 billion of cash in circulation, €307 billion, or one third, was in the form of €500 notes by the end of 2015. But little is known about these notes, beside the fact that they are generally refused by shop-keepers and that citizens are hardly aware that they exist.”

What could possibly explain this trend? Well, here is one big part of the explanation.

“While most countries print about 10% of their national wealth in banknotes each year, Luxembourg printed double the value of its GDP in cash in 2014 alone.”

Is this because Luxembourg contains a large financial centre? Well, no. Euractiv:

“The country may have an outsized financial sector, “but this mostly handles business finance and asset management, not street markets… there is no good reason why they need so much cash,” a French expert said.

(And the rest of that story is worth reading.) Luxembourg, of course, ranks at Number Six in our Financial Secrecy Index.

So we are, thankfully, seeing movement on no longer printing these criminal vehicles. But why — why on earth — stop there? Trillions are still out there, in circulation, doing the crooks’ dirty work, every day. Why not recall them? Say that after a certain date, they will no longer be recognised as worth anything?

The relatively small cost and hassle of converting those notes into smaller-value notes would be far, far outweighed by the benefits of making life harder for the world’s heroin smugglers and people traffickers.

We can think of two big, related reasons reason why this isn’t happening.

First, as a recent paper outlines:

“Central banks would lose some seignorage income from eliminating high denomination notes. However, this loss of income would be more than offset from benefits in increased tax collection and lower crime, corruption and terrorism. In any case, for central banks to be providing high denomination notes to those conducting illegal activities because doing so generates income seems a very difficult policy stance to defend.”

Second, more viscerally, it’s an attitude, that says “we like the money, and we don’t give a damn if it harms other countries.”

An offshore attitude, if ever there was one.

Read more:

“Calling in the Big Bills” James S.Henry, May 1976

“How to Make the Mob Miserable.” James S.Henry, Washington Monthly, June 1980

Making it Harder for the Bad Guys: The Case for Eliminating High Denomination Notes, Peter Sands, Harvard Kennedy School, 2016

Related articles

UN tax convention hub – updates & resources

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

Taxing windfall profits in the energy sector

14 January 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

Keep your hands off my money.