Nick Shaxson ■ The ALEC rankings: does smaller government mean higher growth?

This post originally appeared at Fools’ Gold, a TJN-supported site about “competitiveness”.

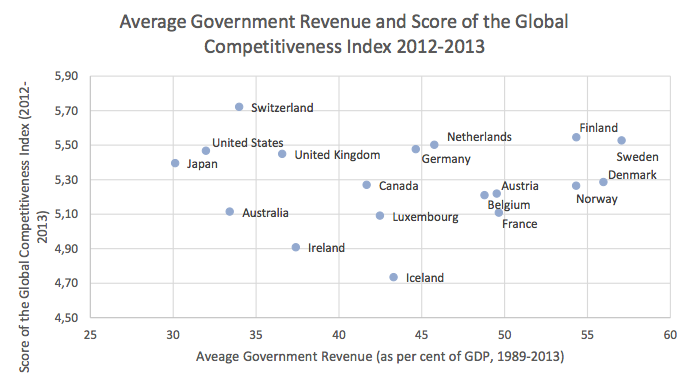

There are a lot of ‘competitiveness’-related rankings of countries and states out there, from the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, to the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings. (We’ll address some of these in due course.) It’s interesting to note, for starters, that the highly taxed, highly regulated Scandinavian economies seem to do just as well as their low-tax, lightly regulated peers. Recently we made up a little graph to illustrate this, looking at the WEF’s ranking:

Source: World Economic Forum, Conference Board. The sample of countries included those with comparable levels of GDP per capita, and excluding micro-states which often have their own ‘tax haven’ growth dynamics. We used states with GDP per capita (PPP) of above $20,000 on average from 1989-2013. Source: Conference Board data tables.

There’s no obvious trend here, is there? The high-tax countries seem to be just as ‘competitive’ as the low-tax ones, it seems, even on the WEF’s measures, (which are somewhat skewed toward the low-tax, light regulation model.) The non-trend you see in this graph is just as Martin Wolf, Paul Krugman and various others would have predicted.

Now ‘competitiveness’ in these rankings is usually taken to be a pointer for future economic growth potential and as Krugman commented a few days ago in a post entitled ‘Competitiveness and Class Warfare’:

“Economic growth is pretty insensitive to policy: France and the US are at the extremes of advanced-country regimes, yet there’s not much difference in their long-term performance.”

The ALEC economic outlook ranking is, in my assessment, a manifestation of faith based economics.

– Menzie Chinn, University of Wisconsin

Wolf made this point from a tax perspective not so long ago, with supporting graphics. As he put it:

“The spread in the average tax ratio is quite large, at 26 per cent of GDP, from Japan to Denmark. It is even quite surprising that such a spread seems to have no effect on economic performance. . . . a tax burden within the range of 30 per cent to 55 per cent of GDP) tells one nothing about a country’s economic performance. It is far more a reflection of different social preferences about the role of the state. What matters far more are culture, quality of institutions, including law, levels of education, quality of businesses, openness to trade, strength of competition and so forth. My conclusion is that the focus on the tax burden is misguided. Alternatively, the economic arguments are a cover for (perfectly understandable) self-interest.”

(There’s more on the theory backing these findings here.)

Now in today’s post, complementing our earlier U.S.-focused post on corporate handouts, we’ll look at a ranking called “Rich States, Poor States: ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index,” in which the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a business lobby group, ranks states according to how business-friendly their policies are. U.S. states are a particularly interesting petri dish for investigating this stuff, not least because Iowa is more like Vermont than France is like the United States.

ALEC claims that its influential Economic Outlook ranking (there’s also an Economic Performance Ranking) is a good pointer for which states will grow and which won’t.

But is it any use?

Well, a ranking that places New York in last place, and Utah in first, is clearly quirky. And warning bells should ring for anyone looking at Alec’s webpage on this study, because it’s got the laughable Arthur Laffer as one of the main authors. We’ll write more about him soon.

Bloomberg commentator Noah Smith looks at it in more detail:

“Alec lists 15 factors that it claims boost state growth rates. These boil down to low taxes, low levels of government spending and light regulation. In other words, these policies are similar to the ideas John Cochrane describes, and that pro-free-market economists have been promising us will boost growth since time immemorial. It’s a simple prescription: shrink the state, cut taxes and the economy will grow.”

Do the ‘competitive’ and ‘business-friendly’ policies that Alec’s proposing actually work?

The answer seems to be a resounding ‘no’. Bloomberg continues:

“Menzie Chinn, an economist at the University of Wisconsin, applied his formidable statistics skills to investigating the impact of ALEC’s rankings on actual state growth levels. What he found was startling — the ALEC rankings didn’t predict a state’s growth within one year, three years or six years. . . . In fact, when Chinn controls for a number of other variables, such as urbanization rates, weather and access to waterways, he finds that there may even be a negative relationship between the ALEC rankings and growth — in other words, states that ALEC claims have more business-friendly policies might actually grow more slowly!”

The exclamation mark at the end of that is a testament to the fact that the conventional wisdom about corporate handouts and competitiveness has become so ingrained that evidence of the overwhelming, long-established truth comes as a big surprise to so many people.

Here’s one of Chinn’s graphs, just for illustration. He concludes:

Here’s one of Chinn’s graphs, just for illustration. He concludes:

“Bottom line: The ALEC ranking, which purports to measure business-friendly policies, is not correlated with real GSP growth, either short term or medium term. . . the ALEC economic outlook ranking is, in my assessment, a manifestation of faith based economics.”

Smith also points to a report by the Iowa Policy Project, a think tank, and Good Jobs First, which we recently blogged. Their analysis essentially reached the same conclusions as Chinn did. They investigated ALEC’s factors of competitiveness individually, and found that none of them had much of a relationship to growth.

A couple of graphs from that study paint a similar picture.

Those are all negligible correlations, and the study provides a number of others. It’s funny how all the graphs in this post seem to look roughly the same. At the end of the day, though, this should not be surprising: tax is a transfer within an economy, not a cost to an economy — so it’s not obvious how tax cuts necessarily boost growth. Still, that’s not the story you’ll hear in much of the media.

The study concludes:

“Despite the long-established body of evidence regarding the sources of growth, Rich States, Poor States consistently fails to acknowledge where state prosperity comes from and the vital role of state government investments in ensuring effective economic development. Its focus instead is on measures that would produce growth without development, or would merely facilitate the greater accumulation of wealth by those already the richest.”

Which is, essentially, the story of the Competitiveness Agenda.

Now what’s been written about in this blog generally concerns how these various policies and factors affect economic growth. But focusing on headline economic growth, and GDP, glosses over a lot of different things, like wealth and income distribution. Once you start to take these different things into account, the graphs can sometimes acquire a very different shape. Such as this one:

Source: The Social Benefits and Economic Costs of Taxation: A Comparison of High and Low-Tax Countries, By Neil Brooks and Thaddeus Hwong, Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives, Dec 2006, Fig. 2

That study, while somewhat out of date, is nevertheless striking. Their conclusion?

“High-tax countries have been more successful in achieving their social objectives than low-tax countries. Interestingly, they have done so with no economic penalty.”

It would be interesting to update this research.

Related articles

UN tax convention hub – updates & resources

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The Bitter Taste of Tax Dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss Swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

Taxing windfall profits in the energy sector

14 January 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)